Q. Who is going to pay?

A. For this UK government Silicon Valley style venture capitalist entrepreneurship is to come before any kind of state sponsored interventions to mitigate climate change.

Q. What's the price for a system where there are subsidised profits for "winners" and climate disaster for all?A. It will cost the Earth!

The Guardian takes a view . . .

The Guardian Editorial (Tue 28 Jul 2020) says:

The government talks a good game when it comes to radical policymaking. But its failure to invest in a zero-carbon future tells a different story

Senior figures in this government like to view themselves as insurgents against a hidebound Whitehall establishment. This is partly because Boris Johnson won the last election after pledging to “get Brexit done”, breaking the post-referendum stalemate in parliament. But it is also settled wisdom in Downing Street, and in the Treasury, that a more general shake-up is required of Britain’s body politic if it is to become more lithe and nimble, and get ahead of the game.

More evidence of this desire to disrupt came on Tuesday in the form of a speech by Stephen Barclay, the chief secretary to the Treasury. Addressing a centre-right thinktank, Mr Barclay heralded a new era of state spending in which the ethos of Silicon Valley would inform departmental decision-making. In the spirit of west coast venture capitalists, government ministers and their civil servants would back schemes that took risks and which would therefore sometimes fail. The interminable delays and inveterate caution that have blighted government projects and investment would become a thing of the past. Inculcating this new Whitehall worldview is seen as fundamental to speedily delivering the “infrastructure revolution” promised by Mr Johnson at the end of last month.

The rhetoric is beguilingly avant garde and dynamic (Mr Barclay talked of the Treasury’s “new radicals”). It should also be said that the prospect of a proactive industrial strategy is welcome after lost years of lazy, laissez-faire rhetoric from the likes of George Osborne. But it is ironic that while the government talks a good game, it risks falling grievously behind Britain’s competitors in one of the growth areas that will define the future. The progress made towards a post-Covid-19 green recovery for Britain is proceeding at a snail’s pace. By contrast, Germany, France, South Korea and others have unveiled plans that will pump vast amounts of government money into developing a low-carbon economy. Last month, Berlin announced a £9bn national hydrogen strategy, which it sees as a route to decarbonising transport and core domestic industries, and achieving global leadership in a new sector. Britain has yet to show anything like the same level of environmental ambition.

Renowned climate experts such as Nicholas Stern and Lady Brown of Cambridge, the chair of the Carbon Trust, would like to see the establishment of a new green investment bank to generate some momentum and confidence. Lord Stern estimates that about £20bn worth of public money would be needed to set one up. This would be a certain catalyst for major private investment; one recent report estimated that £5bn in public funds could attract up to £100bn in private capital for green projects. The energy minister, Kwasi Kwarteng, has declared his support for the idea. But following parliamentary recess, no decision seems likely before Rishi Sunak’s autumn statement.

There is no more time to lose. As Lady Brown has pointed out, in areas such as the production of green hydrogen, Britain has world-leading innovators in a market that is still embryonic and in need of support. Given a fair wind, these companies could expand to become global players in the developing market for green technologies, as well as driving a new generation of carbon-neutral infrastructure at home. But vibrant green growth will only become a reality if government plays its part in a committed public-private partnership.

According to the Committee on Climate Change, Britain is manifestly not on course to meet its legally binding target of net-zero emissions by 2050. The committee chair, John Gummer, told a government inquiry that this was because the “radical things” that needed to be done to shape a green recovery were not being done. A properly funded and ambitious green investment bank could be a gamechanger. Mr Barclay’s “new radicals” should get to it.

The price for 212 environment activists was to pay with their lives

Under the headline and subheading:

Record 212 land and environment activists killed last year

Global Witness campaigners warn of risk of further killings during Covid-19 lockdowns

Patrick Greenfield and Jonathan Watts report for the Guardian (Wed 29 Jul 2020). They write:

A record number of people were killed last year for defending their land and environment, according to research that highlights the routine murder of activists who oppose extractive industries driving the climate crisis and the destruction of nature.

More than four defenders were killed every week in 2019, according to an annual death toll compiled by the independent watchdog Global Witness, amid growing evidence of opportunistic killings during the Covid-19 lockdown in which activists were left as “sitting ducks” in their own homes.

Colombia and the Philippines accounted for half of the 212 people killed last year, a surge of nearly 30% from 164 deaths in 2018 and 11 more than the previous record in 2017. Most killings went unpunished and the true number of deaths is likely to be much higher as many go undocumented.

The mining industry was linked to the most land and environmental defender deaths in 2019, according to the report, followed by agriculture, logging and criminal gangs. Indigenous communities around the world continue to face disproportionate risks of violence, making up 40% of murdered defenders last year.

Alongside the 2019 figures, campaigners expressed concerns that slow or deliberate inaction from governments and corporations to protect vulnerable communities from Covid-19 has led to higher infection rates, raising fears of opportunistic attacks on defenders.

In March, the Colombian indigenous leaders Omar and Ernesto Guasiruma were killed while isolating at home after meeting a local mayor who had tested positive for Covid-19. Two of the victims’ relatives were seriously wounded in the attack.

In Brazil, where 24 people were killed in 2019, indigenous communities have warned they “are facing extinction” in the pandemic, with leaders accusing the far-right president Jair Bolsonaro of “taking advantage” of Covid-19 to eliminate indigenous people.

In Colombia, where deaths more than doubled last year to 64, the most Global Witness has ever recorded in one country, murders of community and social leaders have surged dramatically.

Shifts in local power dynamics after the 2016 peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Farc have been cited as a driver of the rising violence, especially in rural areas, where criminal gangs are repositioning themselves in formerly guerrilla-held regions.

With many paramilitary and criminal groups still highly invested in the drugs trade, the NGO recorded 14 deaths in Colombia linked to a crop substitution programme that offers coca farmers grants to switch to alternatives like cacao and coffee in 2019.

“Agribusiness and oil, gas and mining have been consistently the biggest drivers of attacks against land and environmental defenders – and they are also the industries pushing us further into runaway climate change through deforestation and increasing carbon emissions,” said Rachel Cox, a campaigner at Global Witness.

“Many of the world’s worst environmental and human rights abuses are driven by the exploitation of natural resources and corruption in the global political and economic system. Land and environmental defenders are the people who take a stand against this.

“If we really want to make plans for a green recovery that puts the safety, health and wellbeing of people at its heart, we must tackle the root causes of attacks on defenders, and follow their lead in protecting the environment and halting climate breakdown.”

Killings continued to rise in the Philippines, which was the most deadly country in the world for people defending their land and environment in 2018, with 48 deaths recorded last year.

They include that of the indigenous leader Datu Kaylo Bontolan, who was killed on 7 April 2019 during a military aerial bombardment in Northern Mindanao, which is at the heart of president Rodrigo Duterte’s plans to convert huge areas of land into industrial plantations.

The Manobo leader had opposed commercial logging and mining in his ancestral heartlands and had returned to the mountainous region to document violence against his community.

While Europe remained the least affected continent, two rangers were killed in Romania in 2019 while working to stop illegal logging in some of the continent’s most pristine forests, numbering among the 19 state and park officials killed worldwide.

More than two-thirds of the verified killings took place in Latin America in 2019, including 33 in the Amazon region alone. Deaths rose from four in 2018 to 14 in 2019 in Honduras, making the Central American country the most dangerous country in the world per capita for land and environmental defenders, according to the report.

The NGO said limited monitoring capabilities in Africa meant deaths there were thought to be underreported, with seven verified murders of environmental activists in the continent in 2019.

Four defenders have been killed every week since the Paris Agreement was signed in December 2015, according to Global Witness, with many more silenced by the threat of attack, intimidation and sexual violence.

Global Witness

The Global Witness Press Release today says:

Mining was the deadliest sector globally with 50 defenders killed in 2019, with agribusiness remaining a threat, particularly in Asia – where 80% of agribusiness-related attacks took place.

There have also been increasing threats and attacks in Romania, including the killing of Liviu Pop. A ranger working to protect one of Europe’s largest, primeval climate-critical forests, Liviu was shot and killed after protecting trees in a country where organised criminal gangs are decimating these forests.

Activists still campaigning and under threat include Angelica Ortiz, one of the prominent Wayuu women defenders from La Guajira, who for years has opposed the largest coal mine in Latin America, as part of efforts to protect water rights for communities living in one of Colombia’s poorest regions. Throughout this campaign, she was threatened and harassed.

The NGO also highlights the ongoing pattern of indigenous communities disproportionately attacked for standing up for their rights and territories – despite research showing that indigenous and local communities manage forests that contain the equivalent carbon of at least 33 times our current annual emissions. In 2019 the Amazon region alone saw 33 deaths. 90% of the deaths in Brazil occurred in the Amazon.

The 2019 figures also expose how over 1 in 10 defenders killed in 2019 were women. Women defenders face specific threats, including smear campaigns often focused on their private lives, with explicit sexist or sexual content. Sexual violence is also used as a tactic to silence women defenders, much of which is underreported.

Despite facing these violent threats and criminalisation, defenders across the world still achieved a number of successes in 2019 – a testament to their resilience, strength and determination in protecting their rights, the environment and our global climate.

In Ecaudor, the Waorani indigenous tribe won a landmark ruling to prevent the government auctioning their territory for oil and gas exploration. In Indonesia, the Dayak Iban indigenous community of central Borneo in Indonesia secured legal ownership of 10,000 hectares of land, following a decades-long struggle.

And in a case brought to the UK Supreme Court by communities affected by a large-scale copper mine in Zambia, a judge has significantly ruled that the complaint can be heard in English courts – which could have wider implications for companies failing to come through on their public commitments to communities and the environment.

Executive Summary

Global temperatures reach new highs. Arctic ice continues to melt. Each summer brings news of fires burning through climate-critical forests. If we want to change these headlines, or avoid reading progressively worse ones, it could not be clearer that we are running out of time.

Communities across the world are standing up to carbon-intensive industries and exposing unsustainable business practices wreaking havoc on ecosystems and our climate. These are the people on the frontline of the climate crisis, trying to protect climate-critical areas and reverse these devastating practices.

For years, land and environmental defenders* have been the first line of defence against the causes and impacts of climate breakdown. Time after time, they have challenged the damaging aspects of industries rampaging unhampered through forests, wetlands, oceans and biodiversity hotspots. Yet despite clearer evidence than ever of the crucial role they play and the dangers they increasingly face, far too many businesses, financiers and governments fail to protect them in their vital and peaceful work.

More killings than ever before

This report is based on research into the killings and enforced disappearances of land and environmental defenders between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2019. It also shows the broader range of non-lethal threats and criminalisation that they face.

The documented number of lethal attacks against these defenders continues to rise. Again, we are forced to report that this is the highest year ever for killings – 212 were murdered in 2019. On average, four defenders have been killed every week since December 2015 – the month the Paris Climate agreement was signed, when the world supposedly came together amid hopes of a new era of climate progress. Countless more are silenced by violent attacks, arrests, death threats, sexual violence or lawsuits – our global map provides a picture of the broad array of methods used to deter communities from protecting their land and environment.

Shockingly, over half of all reported killings last year occurred in just two countries: Colombia and the Philippines. Reports show that murders of community and social leaders across the country have risen dramatically in Colombia in recent years – and, with 64 activists killed, those protecting their land and the environment were most at risk. The Philippines, a country consistently identified as one of the worst places in Asia for attacks, saw a rise from 30 killings in 2018 to 43 last year.

Mining was still the most culpable industry – connected with the murders of 50 defenders in 2019. Communities opposing carbon intensive oil, gas and coal projects faced continued threats. Attacks, murders and massacres were used to clear the path for commodities like palm oil and sugar. In 2019, Global Witness documented 34 killings linked to large-scale agriculture – an increase of over 60% since 2018.

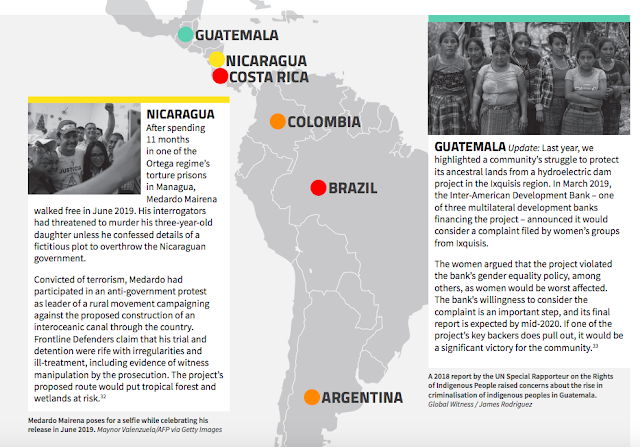

The Global Witness report global map indicates places where environmental defenders have experienced varying degrees of oppression in their efforts and leading, in extreme instances, to their murder.

This includes Europe and the LODE Zone Line in the UK and Poland . . .

In their UK Update: Last year we highlighted the case of three activists who were the first to be jailed in the UK for protesting against fracking. Although their sentences were later overturned, instances of criminalising peaceful protest have continued.

In June 2019, another three protestors – Christopher Wilson, Katrina Lawrie and Lee Walsh – were found guilty of contempt of court. They had breached an injunction banning trespassers in order to protest at a site operated by shale gas company Cuadrilla in Lancashire. It was the first time anyone in the UK has been convicted of breaching an injunction requested by an oil and gas company. All three were given suspended sentences, with one having her sentence reduced on appeal.

In 2018 a UK law on ‘public nuisance’ was used to jail environmental activists for the first time since 1932.

In Poland Global Witness reports on an incident that took place at sea, off the Polish port city of Gdansk: In early September, the worldfamous Greenpeace vessel Rainbow Warrior was boarded during a night-time raid, while moored off the port of Gdansk. Heavily armed and masked border guards stormed the ship, smashing windows with sledgehammers and pointing their weapons at the peaceful activists on board. The Rainbow Warrior was stationed outside Gdansk to block the delivery of coal, as part of a protest against the country’s heavy dependence on coal. Despite the fossil fuel’s severe environmental impact, Poland still uses coal for 80% of its energy needs.

In Kazakhstan . . .

The LODE Zone Line crosses the region of Kazakhstan where land and environmental defenders from the organisation Crude Accountability have paid a high price for opposing the environmental pollution of the Karachaganak oil and gas field in north-western Kazakhstan. They have faced criminalisation, arbitrary detention, threats and harassment from local authorities and police, and even an online smear campaign. In May, Sergey Solyanik was detained by police while taking photos in the village of Berezovka, after the Karachaganak project had forced residents from their homes.

. . . and along the LODE Zone Line in India and Indonesia.

In India Global Witness reports that: India’s Adivasis – indigenous tribal and forest-dwelling communities – came under a twin threat in 2019, as the country’s new citizenship laws and a proposed amendment to the Indian Forest Act put their legal rights and protections at risk.

The new citizenship laws also threatened to make forest communities stateless, as many lack the documents to prove their citizenship. Thankfully, proposed legislation that would have seen millions of tribal and forest dwellers evicted, and given officials the power to shoot people in the forest with virtual impunity, was scrapped after international outcry. But more still needs to be done to keep the stewards of India’s forests safe.

In Indonesia Global Witness reports: Two journalists, Maratua Siregar and Maraden Sianipar, were found stabbed to death on 30 October. They’d been involved in a land dispute between residents of Panai Hilir, North Sumatra, and the Amelia palm oil company which operated a nearby plantation. The palm oil concession where the two men’s bodies were found was closed by the government in 2018 for illegally clearing areas of forest. According to a police statement, some of the suspects arrested for the journalists’ murder admitted it was an act of revenge “linked to palm oil plantation land”. Police also arrested the alleged owner of the palm oil plantation operator for allegedly paying US$3,000 to have Siregar and Sianipar killed, allegations which have been denied. No trial has taken place yet in relation to the deaths of the two journalists.

Papua New Guinea, on the island of New Guinea is also identified in this Global Witness report as a place where environmental defenders have been attacked. The report highlights the case of Cressida Kuala who has paid a high personal cost for her activism. As the founder of the Porgera Red Wara (River) Women’s Association, she works to help indigenous women and girls who have been displaced by mining operations, or sexually abused by mining company employees. After speaking out about the devastating impact of mining operations in her community in Porgera, Kuala has received regular threats and suffered repeated rapes and sexual assaults – most recently, she was raped in early 2019. Yet despite the dangers she faces, she continues to campaign for women’s rights to be recognised by the government and mining companies, including the right to be fully involved in decisions that affect their lives.

Re:LODE and Western New Guinea or West Papua

Neighbouring the independent state of Papua New Guinea, the western half of the island of New Guinea, known as Western New Guinea or West Papua, forms a part of Indonesia and comprises the provinces of Papua and West Papua.

For the Re:LODE project in 2017, the Information Wrap for the cargo created at Pangandaran, on the southern coast of Java, contains two articles that reflect the wider concerns raised in this recent Global Witness report, with accounts of contemporary events taking place in West Papua. One of these articles is called:

Decolonize West Papua! Independence for Papua?

The other is called:

Racism and the "colonial mindset" in the appropriation and exploitation of people and their lands, their natural resources and their labour.

In Australia . . .

Global Witness reports that in August (2019), a protracted legal battle over ownership of the proposed site of the Adani coal mine in central Queensland – between indigenous representatives and the mine’s owners – was settled in Adani’s favour. The legal costs involved bankrupted one activist, Adrian Burragubba, who was ordered to pay AUD$600,000. The Queensland government quashed the claim of the Wangan and Jagalingou people to the land – meaning they can no longer protest on what they claim is their ancestral territory without fear of arrest. “We have been made trespassers on our own country,” said Burragubba. With the wildfires of early 2020 bringing climate change into sharp focus for Australians, the Adani mine will continue to be a source of anger for environmental activists.

Colombia

The global map in the Global Witness report shows the current situation in Central and South America.

Colombia, in the northernmost part of South America, and on the LODE Zone Line, is foregrounded in an entire section of this Global Witness report titled:

Colombia: A rising tide of violence

The Re:LODE project (2017) in the Bluecoat's exhibition in Liverpool, included two video screens with documentation of the LODE project in 1992 and the Re:LODE project of 2017. The video's included the re-presentation of questions posed in the LODE leaflet alongside contemporary questions relevant to the LODE locations over the twenty-five year period of the project.

LODE 1992 and Re:LODE 2017 Cargo of Questions - Santa Fe de Antioquia

A slide on the Re:LODE video features one of the Cargo of Questions 2017 for Lode-zone America in the video documenting the cargo created in Santa Fe de Antioquia:

Why in 2016 did Colombia's homicide rate drop to its lowest in four decades, with 12,000 cases, yet the number of social leaders and human rights defenders killed is on the rise with over 20 murders against activists committed so far in 2017?

This question was prompted by a story by Natalio Cosoy, reporting (19 May 2017) for BBC News, Bogotá:

Why has Colombia seen a rise in activist murders?

An article on the Santa Fe de Antioquia Information Wrap includes reference to this story and others:

Human Rights Defenders increasingly targeted in a post-peace deal power vacuum

Global Witness reports:

COLOMBIA: A RISING TIDE OF VIOLENCE

- 64 defenders were killed in Colombia in 2019 – that’s more than anywhere else in the world and a shocking 30% of documented killings globally.

- This is also over a 150% rise on 2018 and the most murders Global Witness has ever recorded in the country.

- Indigenous groups were particularly at risk – accounting for half the documented killings, despite making up only 4.4% of the population.

Francia Márquez was meeting with other environmental and social justice leaders in the town of Lomitas in May 2019 when they were attacked by armed men. Miraculously, no one was killed in an assault that lasted 15 minutes and during which a grenade was launched at the group.

Francia is one of Colombia’s most prominent Afrodescendant human rights and environmental defenders. She won the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize in 2018 for her activism. This was not the first time she’s been attacked. Throughout a successful campaign to stop illegal mining in La Toma in the Cauca region of

south-western Colombia, she was threatened, harassed and eventually forced from her home.

The Cauca region where Francia and her colleagues were meeting is one of the most dangerous places in the world to stand up for the environment. Over a third of all killings of Colombian land and environmental defenders documented by Global Witness took place there in 2019. But this is a story that is playing out again and again in communities across the country who are on the frontline of protecting the planet, and attacks against leaders have reached crisis point.

A FAILING PEACE AGREEMENT AND ESCALATING ATTACKS

Global Witness recorded more killings of land and environmental defenders in Colombia in 2019 than anywhere else in the world. Indigenous groups in were particularly at risk – accounting for half the documented killings, despite making up only 4.4% of the population.

The Constitutional Court declared that several indigenous cultures are at risk of extinction, with the National Organisation for Indigenous People of the Colombian Amazon claiming: “A genocide is being presented against the indigenous communities.” So why are defender deaths escalating in Colombia? The 2016 Peace Agreement ended the decades-long war between government forces and FARC rebels, but it has not brought peace to large parts of the country. Organised criminal and paramilitary groups – many of which have taken over formerly FARC-controlled areas – are responsible for a high percentage of the killings we document:57 Global Witness data* attributed just under a third of defender deaths to these groups in 2019. In a culture of widespread impunity, the perpetrators can be confident of escaping justice – it is estimated that 89% of the murders of human rights defenders do not end in a conviction. Some argue that this impunity is fuelled by a government that dismisses these killings as localised crimes, rather than seeing them as part of ‘an attempt by various actors to continue to repress social change in a violent way’.

“Not everything is going well with the peace agreement. There was misunderstanding that putting an end to the situation with FARC rebels would end the violence – but we see the violence is increasing.” Angélica Ortiz

A key part of the peace agreement were incentives to move farmers away from coca cultivation, thereby cutting cocaine production and disrupting a drugs trade that had fuelled the conflict. Coca growers were offered grants to start growing alternatives such as cacao and coffee. But this crop-substitution programme was badly implemented, with many farmers not receiving their payments, putting the livelihoods of up to 100,000 families in doubt. Those who supported or participated in the programme have been threatened by criminal organisations and paramilitaries still highly invested in the drugs trade – Global Witness recorded the deaths of 14 people targeted in this way.

CLIMATE OF FEAR

The murder of land and environmental defenders takes place in a wider climate of persecution and non-lethal threats that seek to instil fear in those brave enough to

speak out. Angélica Ortiz, a Wayuu indigenous woman from La Guajira in northern Colombia, knows this only too well. She is the secretary-general of the Fuerza de Mujeres Wayuu, who have led protests against the huge coal-mining project, El Cerrejón. According to recent research, this is one of five companies whose operations gave rise to 44% of the attacks on defenders raising concerns about them between 2015 and 2019.

Angélica’s organisation has faced repeated threats – six in 2019 alone – allegedly from paramilitary groups, as well as public smear campaigns. The organisation says

the government has given no adequate response to their repeated requests for protection, dating back to 2018.

GROWING THREATS AGAINST WOMEN

Defenders Janeth Pareja Ortiz and Angélica Ortiz, from the Ipuana clan, in the middle of the Arroyo Aguas Blancas riverbed. Both received death threats after denouncing mining companies that have contaminated their community’s land and standing against the violence of the armed actors who control the region.

Women defenders like Angélica and Francia are facing increasing threats in Colombia – with the UN documenting almost a 50% rise in the killing of women between 2018 and 2019. They are reportedly more likely than men to face verbal abuse and surveillance

as tactics to intimidate and silence them.

The targeted killing of social leaders, including those protecting their land and environment, was one of the issues that sparked widespread protests in cities across

the country during November. The protests were a sign of growing discontent with the lack of progress in implementing the peace agreement and the ongoing violence. So far, however, President Ivan Duque’s response has been lacklustre and insufficient, according to the country’s civil society groups.

The day after the attack on her life, Francia Márquez took to Twitter with a call for the future: “The attack that we leaders were victim to yesterday in the afternoon, invites us to continue working towards peace in our territory, in the department of Cauca and in our country, there has already been too much bloodshed.”

DEFENDERS’ RECOMMENDATIONS:

Fuerza de Mujeres Wayuu and Programa Somos Defensores call on the Colombian Government to:

- Fully implement the provisions of the 2016 Peace Agreement, including a comprehensive rural reform programme that guarantees the economic integration of poor rural communities through land titling and extending state services to rural communities.

- Recognise and support the National Commission of Security Guarantees (NCSG) to function fully, as outlined under the 2016 Peace Agreement. The NCSG should develop a plan (funded and implemented by the government) to investigate and dismantle paramilitary and armed groups.

- Ensure justice by investigating and prosecuting the material and intellectual perpetrators of lethal and nonlethal attacks against defenders.

- Publicly recognise the important role of human rights defenders. Respond to the intensifying threats against them by developing, funding and implementing safety and protection measures – ensuring that any plan builds on the collective experiences and participation of human rights defenders and social leaders.

COLOMBIA AND CLIMATE CHANGE

Colombia faces the grim prospect of intensifying floods and droughts, as the effects of climate change continue to bite, according to the UN.63 Many communities are already at increased risk of flooding and landslides.

After years of conflict, the country has one of the highest proportions of internally displaced people in the world, with insecure land rights making many rural communities especially vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. The government’s own report under the Paris Agreement underscores the importance of addressing the climate crisis on the country’s road to peace. Yet, the very same government continues to pursue land- and carbon-intensive industries – Colombia is the world’s fifth biggest coal exporter and has sizeable oil, gas and palm oil sectors.66

At the same time, the country has reversed steps to allow citizens – including land and environmental defenders – to reject the approval of extractive projects.

Extractive projects . . .

There is a common thread along the LODE Zone Line that weaves extractive projects, especially mining, and the destruction of primary forest, and the consequent catastrophic impacts upon people, the global climate and the habitable quality of the environment.

Living in the Shadow of Colombia’s Largest Coal Mine

Indigenous communities in one of country's poorest provinces say El Cerrejón is harming health and environment

Ynske Boersma writes Jan 30, 2018 for the Earth Island Journal

The sun is rising in the Indigenous reserve Provincial, in the northern Colombian province of La Guajira. The morning silence is broken by a pounding sound, emanating from a nearby mining pit just a few hundred meters from the community.

El Cerrejón is among the world’s largest coal mines. Communities in La Guajira, one of Colombia’s poorest provinces, say mining activities are polluting their water and harming their health.

“That noise continues day and night,” says local Luz Angela Uriana while grinding corn for breakfast. The air is heavy with dust, and smells vaguely of sulphur and burning coal. Smoke plumes rise above the mine. “And when they do their daily coal blast, our houses vibrate like mobile phones.”

Bordering the protected communal lands of the Indigenous reserve lies El Cerrejón, one of the world´s biggest open-cast coal mines. The company operating the mine, also named Cerrejón, extracts about one hundred tons of coal a day, with an international coal market share of 3.9 percent in 2016. Since the mine began operating in 1986, Cerrejón has exploited about 13,000 hectares of the 69,000 the company holds in concession. About 100 communities are affected by the mining activities, most Indigenous Wayúu, a smaller portion of African-Colombian descent.

The company, co-owned by mining giants Glencore, Anglo-American, and Billiton-BHP, says it complies with Colombian law and points to its sustainable development programs, such as their reforestation project and the relocations of local communities living close to the mine. But locals say the mining operations have taken a drastic toll on their health and quality of life. And they are fighting back.

In 31 years of operation, the people of Provincial have seen the mine inch closer and closer to their territory, which lies within one of Colombia’s most impoverished provinces. Too close, according to locals, who say they suffer from respiratory problems and skin diseases due to the pollution caused by mining operations. They say daily coal blasts release giant clouds of dust that pollute the air, water, and soil. Another problem is the spontaneous ignition of mined coal, which releases toxic heavy metals into the environment.

Many children in the vicinity of the mine suffer from respiratory problems, including three-year old Moisés, Luz Angela Uriana’s son. “The problems started when Moisés was eight months old,” Uriana told me. “He had a high fever, and coughed as if he was choking. Now he is three years old, and still fighting for his life. He can´t run, nor shout, and coughs at night.”

Little can be done at the local hospital. “The paediatrician says Moisés will only get better if we move to another place, but where should we go? We belong to this territory,” says Uriana, crying.

Ricardo José Romero, coordinating doctor of the local hospital Nuestra Señora del Pilar in nearby Barrancas, confirms he has seen an increase in illnesses that could be linked to mining operations. A staggering 48 percent of patients arrive at the hospital with acute respiratory problems. The hospital even has a special emergency area for respiratory illnesses. During my visit, five children were waiting for treatment.

“The illnesses we diagnose most in this hospital are acute respiratory problems, asthma, and COPD [Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease]. These symptoms occur with people living in the vicinity of the mine, and employees of El Cerrejón,” says Romero. “Also, we see many patients with skin problems, and cancer.”

“But as a small hospital without enough funding, there is not much we can do here,” continues Romero. “The government allows this multinational to exploit our environment, but doesn´t care about the consequences for its inhabitants. In more than 30 years that the mine has been here, not a single study has been done about the impacts on the health of people affected by their operation.”

According to the company itself, Cerrejón holds no responsibility for the rise of respiratory illnesses in the vicinity of their operation. “It´s all a matter of perception,” says Victor Garrido, manager of social affairs for El Cerrejón. “The inhabitants think [they have] a real problem, but we consider it an imaginary problem.”

Garrido then points to the Colombian environmental standards the company says it complies with. He doesn’t mention, however, that environmental standards in Colombia are far below international recommendations. For example, the World Health Organization recommends that annual mean concentrations of PM10 — exposure to which is associated with respiratory and cardiovascular problems — not exceed 20 mg/m3, while the Colombian recommendation is set at 50 mg/m3.

The mine has also taken a severe toll on the region´s water resources. The mining area is traversed by the province´s most important river, the Rancheria. About 55,000 people depend on the river as their only water supply, in a province so dry that it rains no more than two months a year, with an average rainfall between 500 and 1000 mm per year.

After 31 years of coal extraction, the river has become a muddy, contaminated stream. El Cerrejón uses at least 34 million liters of water a day for their operation, according to Cerrejon official Gabriel Bustos. The water is extracted from superficial and subterranean water sources from the Rancheria and its tributaries. During the extreme drought caused by El Niño between 2012 and 2015, the Rancheria dried out completely in some parts, causing severe food shortages among local people in the area, whose animals and crops died from the lack of water.

According to Indepaz, a Colombian non-profit focused on peace and development, toxic wastewater from the mine contaminated with heavy metals and fuel residues are also discharged into the local waterways. Recent studies conducted by Indepaz show that concentrations of heavy metals like zinc, lead, magnesium, and barium start to rise at the points where Cerrejón discharges wastewater into the rivers and streams.

Some 55,000 people depend on the Rancheria river for water, which locals say has been depleted and contaminated since El Cerrejón began operating more than three decades ago.

Moreover, in samples taken from the wells of several communities close to the mine, Indepaz found concentrations of heavy metals making the water unsuitable for human consumption. In the well in Provincial, researchers found arsenic and magnesium levels above those permitted for these metals. Specifically, in August 2016 they found arsenic levels of 0.026 mg/liter. The permitted value of arsenic in Colombia is 0.01 mg/liter. These metals, naturally present in rock and carbon, get dispersed in the environment by mining activity, contaminating the air, water and soil.

Cerrejón denies allegations that their operation is polluting local water resources, but Golda Fuentes, an investigator with Indepaz, contests this: “El Cerrejón cannot possibly say that they are not contaminating the environment. We found that these concentrations are incompatible even with the Colombian standards for a healthy environment. The problem is that the laws applying to mining companies allow this contamination.”

What’s more, an estimated fifteen tributaries of the Rancheria have disappeared entirely due to coal extraction and diversion projects, says Mauricio Enrique Ramírez Álvarez, former director of the province´s Planning Department. The people who used to rely on these water sources now rely on wells, which are often contaminated. Local communities have been fighting against expanded mining operations for years. A plan to divert a 26-kilometer-section of the Rancheria River in order to extract an estimated 500 million tons of coal underneath it was suspended in 2012 due to mounting social protests. And recent protests have also delayed plans by Cerrejón to divert another local stream, the Arroyo Bruno, one of the most important tributaries of the Rancheria. During the the drought in 2012-2015, the Bruno was the only major water resource left in the area.

In response to the Bruno diversion plan, locals from El Carrejon went to court. They demanded suspension of the plans, noting that the company had failed to consult them about the project as required under Colombian national law. Last August, the judge ruled in their favor, suspending the expansion plans until these consultations have been carried out. Moreover, he ordered the Colombian Institute for Geology Terrae to revise the environmental studies for the project, which the company had relied on for its licence to divert the stream.

The judge found that these studies omitted important information about the effects of the diversion on subterranean water bodies, says Julio Fierro Morales from Terrae. “Whereas these water bodies are crucial for the survival of the stream.”

“The moment El Cerrejon starts extracting coal from underneath the original river bed, the underground aquifers which store water will be destroyed, drying out the stream,” Morales explains. “Besides, the company should have consulted the communities about the project. But Colombian authorities are that weak and corrupt that Cerrejon gets away with everything.”

Back to the Wayuu-reserve Provincial, Luis Segundo Bouriayu is more than a little frustrated. “Before we could grow our own food, and eat fish from the river,” he says. “But since the mine is here, nothing will grow anymore because of the contamination of the river and soils. The water we drink we need to buy, without having the money to pay for it.”

“Estamos de todos los lados jodidos,” he concludes:

“We´re fucked on all sides.”

Q. Why are Indigenous People in the front line?

A. Because their spatial and cultural zones are invariably on the expanding frontiers of capitalist expansion and exploitation of the planet's resources!

In their book A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things, Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore present a new approach to analysing today’s planetary emergencies.

How has capitalism devastated the planet—and what can we do about it?Nature, money, work, care, food, energy, and lives: these are the seven things that have made our world and will shape its future. In making these things cheap, modern commerce has transformed, governed, and devastated the Earth.

The "separation" of people from nature is part of the ecology of capitalism, as they describe, and what we might call, the modern, contemporary and continuing "fall of man", or Paradise Lost. This is what they say:

The notion that individuals are part of collective units greater than themselves isn't new - humans have long given names to and established boundaries around social groups: being part of the polis, the city, the Middle Kingdom, Christendom, the chosen people, and so on. But modern society has a historically unique antonym: nature. On the other side of "society" are not other humans but the wild. Before nation came society. Before society could be defended it had to be invented. And it was invented through the policing of a strict boundary with nature.Where European capitalism thrived was in its capacity to turn nature into something productive and to transform that productivity into wealth. This capacity depended on a peculiar blend of force, commerce, and technology, but also something else - an intellectual revolution underwritten by a new idea:

Nature as the opposite of Society.

This idea gripped far more than philosophical minds. It became the common sense of conquest and plunder as a way of life. Nature's bloody contradictions found their greatest expression on capitalism's frontiers, forged in violence and rebellion.

We take for granted that some parts of the world are social and others are natural. Racialized violence, mass unemployment and incarceration, consumer cultures - these are the stuff of social problems and social injustice. Climate, biodiversity, resource depletion - these are the stuff of natural problems, of ecological crisis. But it's not just that we think about the world in this way. It's also that we make it so, acting as if the Social and the Natural were autonomous domains, as if relations of human power were somehow untouched by the web of life.

Real abstractions

Moore and Patel explain how in their book they use these words - Nature and Society:

. . . in a way that's different from their everyday use. We're capitalizing them as a sign that they are concepts that don't merely describe the world but help us organize it and ourselves. Scholars call concepts like these "real abstractions." These abstractions make statements about ontology - What is? - and about epistemology - How do we know what is? Real abstractions both describe the world and make it. That's why real abstractions are often invisible, and why we use ideas like world-ecology to challenge our readers into seeing Nature and Society as hidden forms of violence. These are undetonated words. Real abstractions aren't innocent; they reflect the interests of the powerful and license them to organize the world.

At the core of these novel solutions was global conquest, not just by guns but also by making new frontiers, at once cultural and geographical. Life and land between money and markets became ways to treat and fix crises across the span of capitalism's ecology.

At the heart of this relation with nature lay profit, and its poster child is Christopher Columbus. Columbus, who crops up in every chapter as an early practitioner of each of the strategies of cheap things, came to the Caribbean with not just the conqueror's gaze but an appraisers eye - one sharpened in Portuguese colonial adventures off the shores of North Africa. He launched a colonization of nature as pecuniary as it was peculiar.

Profit didn't come just from trade, however. Nature had to be put to work. An early practical use of the division between Nature and Society appeared in the colonial reinvention of the encomienda. Originally just a claim on land, the ecomienda became a strategy to shift certain humans into the category of Nature so that they might more cheaply work the land. When the Spanish crown was battling for territory in Iberia, encomiendas were a way of managing its spoils. These were temporary land grants given by the king to aristocrats so that they might profit from estates previously occupied by Moors. In the Caribbean, encomiendas were transformed from medieval land grants into modern labor grants, allowing not just access to the land but the de facto enslavement of the Indigenous people who happened to be there. Rights of dominion came to encompass not just territory but also flora and fauna; Indigenous people became the latter. Over time, the encomienda system came to comprise a diversity of labor arrangements, combining legal coercion with wage labor.

This meant that the realm of Nature included virtually all peoples of colour, most women, and most people with white skin living in semicolonial regions (e.g., Ireland, Poland).

This is why in the sixteenth century Castilians referred to Indigenous Andeans as naturales.

The LODE Project of 1992 included Port Hedland as the location for the creation of a LODE Cargo. The port has two main exports, salt and iron ore. The salt is extracted from the ocean filled salt pans running along this part of the coast, and the iron ore is extracted from the iron ore rich Pilbara.

LODE 1992 and Re:LODE 2017 Cargo of Questions - Port Hedland

BHP, a joint shareholder in the Colombian open cast coal mine El Carrejon is extending its mining operation in the Pilbara, in the hinterland of Port Hedland. The possible consequences of the expansion of this mining operation include the destruction of at least 40 Aboriginal sites.

BHP to destroy at least 40 Aboriginal sites, up to 15,000 years old, to expand Pilbara mine

Exclusive: WA minister gave consent to BHP plan just three days after Juukan Gorge site was blown up by Rio Tinto in a move that has horrified the public

Lorena Allam and Calla Wahlquist reported on this story for the Guardian (Wed 10 Jun 2020):

Mining giant BHP Billiton is poised to destroy at least 40 – and possibly as many as 86 – significant Aboriginal sites in the central Pilbara region of Western Australia (WA) to expand its A$4.5bn (£2.4bn) South Flank iron-ore mining operation, even though its own reports show it is aware that the traditional owners are deeply opposed to the move.

In documents seen by Guardian Australia, a BHP archaeological survey identified rock shelters that were occupied between 10,000 and 15,000 years ago and noted that evidence in the broader area showed “occupation of the surrounding landscape has been ongoing for approximately 40,000 years”.

BHP’s report in September 2019 identified 22 sites of scattered artefacts, culturally modified trees, rock shelters with painted art, stone arrangements, and 40 “built structures … believed to be potential archaeological sites”.

Under section 18 of the Western Australian Aboriginal Heritage Act, the traditional owners – in this case the Banjima people – are unable to lodge objections or to prevent their sacred sites from being damaged.

They are also unable to raise concerns publicly about the expansion, having signed comprehensive agreements with BHP as part of a native title settlement. BHP agreed to financial and other benefits for the Banjima people, while the Banjima made commitments to support the South Flank project.

But the Banjima native title holders told the WA government in April they did not want any of the 86 archaeological sites within the project area to be damaged, saying the “impending harm” to the area “is a further significant cumulative loss to the cultural values of the Banjima people”.

Guardian Australia has seen correspondence from an archaeological adviser to the Banjima to the WA government in April this year in which they say they “in no way support the continued destruction of this significant cultural landscape” but “are equally aware” they cannot formally object to the section 18 application.

This letter in April followed one sent in December 2019 in which the native title holders said: “The significance of the sites impacted by the notice to Banjima people is such that Banjima people cannot and do not support the destruction of those sites as proposed by the notice as to do so would be inconsistent with their cultural obligations to protect those sites.” They would “suffer spiritual and physical harm if they are destroyed”.

They said they were “worried about the cumulative impact of so many sites being the subject of a single notice for destruction and that not one of the sites is deemed worthy of protection in situ by BHP”.

BHP’s 2019 report said “it had taken into account the views and recommendations provided by the Banjima representatives during the consultation and inspection” but decided it was “not reasonably practicable for BHP to avoid the eighty-six (86) potential archaeological sites” at the South Flank mine development area.

BHP suggested the areas could be excavated, salvaged or deconstructed but also noted the Banjima did not want any of the objects or heritage values within the 86 potential archaeological sites to be removed or relocated.

BHP also offered to engage “a suitably qualified expert to digitally capture the extent and form of each stone arrangement using DPGS [differential global positioning system] and drone footage, with a view of creating a three-dimensional computer model and video”.

“Any cultural material salvaged as part of these programs shall be stored in the cultural repository at the BHP Mulla Mulla Heritage Office until a different location is nominated by the Banjima people,” the company’s assessment report said.

All 86 sites identified in the BHP application were assessed by WA’s Aboriginal Cultural Materials Committee, which controls the protection of heritage, but only 40 were considered by the ACMC to meet the threshold required to be a protected heritage site, despite the Banjima saying all 86 should be protected.

BHP said ministerial consent for its section 18 application covered approximately 40 heritage sites.

“We speak regularly with the Banjima community and have reiterated our commitment to working closely with them through the lifecycle of the South Flank development to minimise impacts on cultural heritage,” a spokesman for BHP said.

The revelations follow the apology last week by the chief executive of Rio Tinto iron ore, Chris Salisbury, for destroying the rock shelter in Juukan Gorge, which was blown up in mining works at the Brockman 4 iron ore mine near Tom Price in the Pilbara region on 24 May, saying there had been a “misunderstanding” with traditional owners the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people.

On Tuesday, more than 300 protesters gathered in face masks outside the company’s offices on St George’s Terrace in Perth to call for Salisbury’s resignation.

Protest organiser Robert Eggington, a Noongar man, said Rio Tinto had exploited the weakness of WA’s 48-year-old Aboriginal heritage laws, which have been under review for two years.

“They used that against the people and then turned and blamed [it on] misunderstandings between the company and the custodians of that site,” Eggington said.

Rio Tinto received ministerial consent under the WA legislation to destroy the site in 2013. That legislation does not give traditional owners the right of appeal.

BHP has said the South Flank project will create around 2,500 construction jobs, more than 600 ongoing operational roles and generate many opportunities for Western Australian suppliers. The project is expected to produce ore for more than 25 years.

The Western Australian minister for Aboriginal affairs, Ben Wyatt, confirmed he approved the South Flank expansion on 29 May, three days after the destruction of Juukan Gorge made global headlines.

But he has urged BHP to cooperate with the Banjima under what are now “changed circumstances”.

“As with any agreement, some circumstances can change including the understanding of heritage values of particular sites.

“I urge parties to such agreements to cooperate on management of those changed circumstances.

“I have asked BHP to work with Banjima to do what it can to avoid or minimise the impact on this site, regardless of the section 18 approval.”

Wyatt said impending reforms to the WA Aboriginal heritage legislation will end the section 18 process and reinforce the need for land users to negotiate directly with traditional owners.

Wyatt said he wants to see impacts to Aboriginal sites “limited to the practical extent possible” but that he is “cautious about governments interfering in private negotiations by registered native title holders”.

Companies such as BHP make significant investment decisions on the basis of these agreements with native title groups, which in turn generate substantial benefits, he said.

“Our first principle is to seek to avoid impacts to cultural heritage, through planning and ongoing consultation with traditional owners. This approach is supported by the individual land use agreements we establish in partnership with traditional owners, and is in addition to meeting the requirements of Aboriginal heritage protection laws” a BHP spokesman said.

Mining firms killing off climate action in Australia

This story by Christopher Knaus for the Guardian (Thu 10 Oct 2019) appeared in October last year, pointing to mining firms surreptitious methods aiming to kill off climate action in Australia, according to the Australian ex-PM Kevin Rudd:

Kevin Rudd says industry still has huge influence in a country beset by climate policy torpor

Christopher Knaus writing for the Guardian:

The former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd says three of the world’s biggest mining multinationals have run sophisticated operations to kill off climate action in Australia and continue to wield day-to-day influence over government through a vast lobbying network and an “umbilical” relationship with the Murdoch media.

Australia’s climate policy paralysis has been ongoing for more than decade, from the Rudd Labor government’s doomed attempt to bring in an emissions trading scheme in 2008, to the Liberal prime minister Malcolm Turnbull’s failed attempt to introduce the national energy guarantee last year.

Successive attempts at serious climate action have faced fierce resistance, often led by industry lobbying, and have contributed to the downfall of three recent prime ministers: Rudd, his successor Julia Gillard and Turnbull.

The mining sector’s power to influence Australian politics is infamous. Separate to climate policy, it led an intense campaign against the resource super profits tax – a 40% tax on mining profits – proposed by Rudd in 2010. The industry’s damaging $22m lobbying effort helped depose Rudd and gut the super profits tax, rendering it near useless.

Experts and environmentalists say the industry’s power is derived from political donations, gifts, advertising, paid lobbyists, frequent access and close political networks. Rudd said he felt the full brunt of that influence.

“Glencore, Rio [Tinto] and BHP ran sophisticated political operations against my government, both on climate change and the mining tax,” he told the Guardian. “They worked hard … to get rid of the resource super profit tax, against the interests of other mining companies and the national economy as a whole. They worked hard … in 2013 against the carbon price. They succeeded in both enterprises.”

Rudd attributes the day-to-day influence of the sector to two mechanisms. The first is what he describes as the vast lobbying network it uses to pressure political parties. The second is its close relationship with the Murdoch media, which owns most of the country’s print media. Rudd describes the relationship as “umbilical”.

“When did you last see the Murdoch media critical of any of these corporations?” Rudd said. “Rarely. If ever.”

BHP, Glencore and Rio Tinto, and the Murdoch-owned News Corp, all declined to comment.

The Melbourne University academic George Rennie, an expert on lobbying, sees the mining sector as one of the most powerful groups in Australia. Its power, he says, manifests in an ability to get senior politicians on the phone or to meet face-to-face with relative ease.

“Its ability to access decision-makers is famous, and the experience of the ‘mining tax’ lobbying campaign in 2010 has made both parties afraid to take on mining interests,” Rennie said. “The power of the resources sector comes from its profits – its ability to spend on donations and gifts, as well as its own political advertisements if it chooses.

“There is disproportionate power, so if you want to lobby government for something that the resources sector does not want, you’re very unlikely to get your way.”

The scant publicly available information on political access in Australia backs up Rennie’s view. A Guardian analysis of ministerial diary data compiled by the Grattan Institute thinktank shows the mining and energy sector enjoys frequent access to government leaders in two of Australia’s most important mining states: Queensland and New South Wales.

Mining and energy industry executives met the Queensland premier, deputy premier or treasurer 44 times in 2017-18 alone. That figure excludes renewables companies and energy retailers, and does not count meetings with lesser ministers, backbenchers or bureaucrats.

Access to the highest rungs of power was also significant, albeit less frequent, in NSW. There, the sector secured access to the NSW premier, deputy premier or treasurer 13 times in 2016-17.

The Grattan Institute data shows the mining sector is responsible for the highest proportion of major donations to political parties. Mining interests accounted for one in five donations above $60,000 in 2015-16 and 2016-17.

The Grattan Institute senior associate Kate Griffiths has researched lobbying, donations and political influence in Australia, helping to publish a report last year titled Who’s in the Room? She said the sector differed from others because of its high uptake of commercial lobbyists and its pursuit of face-to-face meetings with ministers.

“There’s also a fair bit of exchange of staff between mining and energy companies and political offices,” Griffiths told the Guardian. “Mining and energy companies have the resources to hire former politicians and political advisers so that can create a certain cosiness that makes both access and influence more likely.”

The revolving door between politics and the mining industry is a feature in both of Australia’s major parties. Brendan Pearson, a former head of Australia’s peak mining lobby group, the Minerals Council of Australia, recently joined the office of the Liberal prime minister, Scott Morrison, as a senior adviser.

On the other side, Gary Gray, a former Labor resources minister, joined the mining industry in his post-political career, including working for the mining services company Mineral Resources Limited.

Martin Ferguson, another former Labor resources minister, is now the chairman of the advisory board to the oil and gas peak industry body, the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association.

Cameron Milner, a Labor strategist, lobbied for the Indian mining giant Adani for five years, before eventually parting ways so he could work on the campaign of the Queensland premier, Annastacia Palaszczuk, in 2017.

The industry also exerts influence in less obvious ways. An investigation by Guardian Australia this year revealed a covert, multimillion-dollar influence campaign being run by C|T Group, the lobbyist firm headed by Lynton Crosby, on behalf of Glencore.

The campaign, known as Project Caesar, included the creation of fake online grassroots groups that spread anti-renewable, pro-coal content to unsuspecting users. It aimed to shift the emotion and tone of the energy debate in Australia to favour coal by using personally relevant messaging, centred on themes of cost, reliability and family security.

Campaign teams also collected material that could be used to embarrass activist groups such as Greenpeace and 350.org.

Dom Rowe, Greenpeace Australia Pacific’s programme director, said Australia’s lack of credible climate policy could be directly attributed to the industry’s influence.

“Considering the vast network of influence and direct access that fossil fuel executives and lobbyists have to senior government ministers, it is little wonder that the Coalition has yet to take any meaningful action on reducing Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, which have been rising for over four years,” Rowe said.

“It’s completely unacceptable that both major parties are abandoning their responsibility to protect Australians from the worsening impacts of the climate crisis, in favour of not biting the hand that feeds.”

Extraction from "nature" of the planet's resources is the classic capitalist model. Short term profit is the required "business as usual" state of affairs.

The consequences, if ignored, lead to the privatization of profit and the socialization of loss.

This is evident in the global climate fight to mitigate the effects of global heating . . .

The Guardian Climate countdown . . .

In 100 days . . .

The Guardian's Climate countdown was launched on Monday 27 July, a series of stories published day by day over the 100 days to the date that the US is poised to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement. John Mulholland writes:

On 4 November, the day after the presidential election, the US is poised to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement. The agreement, which came together after years of diplomacy by the Obama administration and other global leaders, commits 200 countries to chart a new course in efforts to combat climate change.

But very soon the United States may not be one of them.

The Paris climate agreement sets out a global framework to try to stop dangerous climate change and, for the first time, the world’s major carbon emitters stood side by side and committed to do better. But just months after he took office, Donald Trump announced that the US would withdraw from the agreement and would no longer take collective responsibility for the future of the planet.

Since then, Trump has continued to actively work against measures that could tackle the climate crisis. His administration has removed countless environmental protections, boosted the fossil fuel industry, buried the federally mandated National Climate Assessment report, disappeared climate change science from US government websites, and helped foster an anti-science atmosphere throughout his administration.

America’s modern commitment to environmentalism took root exactly 50 years ago when Earth Day protests led to the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency and the Clean Air and Water Act. In just four years, the Trump administration has set about dismantling much of the progress that has been made. By withdrawing from the Paris agreement it will now weaken the global resolve to tackle the climate crisis.

The stakes could scarcely be higher. With your help we can put this issue at the center of our 2020 election coverage. The election will be a referendum on the future of democracy, racial justice, the supreme court, and so much more. But hovering over all of these is whether the US will play its role in helping take collective responsibility for the future of the planet.

The period since the Paris agreement was signed has been the five hottest years on record. If carbon emissions continue, substantial climate change is unavoidable.

Over the next 100 days, Guardian US will publish a series of stories about the many impacts of the climate crisis. The series will focus on people of color and vulnerable communities across the globe, who are uniquely exposed to the dangers of a heating planet. We will examine Joe Biden’s proposals to tackle climate change and whether they are up to the task. And we will elevate the young people whose futures will be shaped by the crisis and the world’s response to it. The series is sponsored by We Are Still In and We Mean Business, but the content is editorially independent from the sponsors.

On 21 September, during Climate Week, we will join with Covering Climate Now and some of the world’s leading media organizations to highlight first-time voters facing a future of environmental peril. We have invited these voters to apply to be Guardian US guest editors on that day.