NOT "clickbait" . . .

The photograph above shows Dan Mouer in Vietnam in 1966. The magazine was sent by his wife, along with a batch of chocolate chip cookies.

The image was used in an Opinion piece by Amber Batura for The New York Times, with the headline:

How Playboy Explains Vietnam

There’s a famous scene about halfway through “Apocalypse Now” in which Martin Sheen’s river boat pulls into a supply base, deep in the jungle. While the crew members are buying diesel fuel, the supply clerk gives them free tickets to a show — “You know,” he says, “the bunnies.” Soon they’re sitting in an improvised amphitheater around a landing pad, watching as three Playboy models hop out of a helicopter and dance to “Suzie Q.”

The scene is entirely fictional; Playboy models almost never toured Vietnam, and certainly not in groups. But if the women were never there themselves in force, the magazine itself certainly was. In fact, it’s hard to overstate how profound a role Playboy played among the millions of American soldiers and civilians stationed in Vietnam throughout the war: as entertainment, yes, but more important as news and, through its extensive letters section, as a sounding board and confessional.Playboy’s value extended beyond the individual soldier to the military at large; the publication became a coveted and useful morale booster, at times rivaling even the longed-for letter from home. Playboy branded the war because of its unique combination of women, gadgets, and social and political commentary, making it a surprising legacy of our involvement in Vietnam. By 1967, Ward Just of The Washington Post claimed, “If World War II was a war of Stars and Stripes and Betty Grable, the war in Vietnam is Playboy magazine’s war.”The most famous feature of the magazine was the centerfold Playmate. The magazine’s creator and editor, Hugh Hefner, had a specific image in mind for the women he portrayed. The Playmate, originally introduced as the Sweetheart of the Month, represented the ultimate companion to the Playboy. She enjoyed art, politics and music. She was sophisticated, fun and intelligent. Even more important, this ideal woman enjoyed sex as much as the ideal man described in the publication. She wasn’t after men for marriage, but for mutual pleasure and companionship.

She enjoys art . . .

The sexualized, yet familiar, "girl next door" . . .

Though following in their legacy, the Playmate models differed from the pinups of World War II. Hefner wanted images of real women their readers might see in their everyday life — a classmate, secretary or neighbor — instead of the highly stylized and often famous women of an older generation. The sexualized, yet familiar, “girl next door” was the perfect accompaniment for soldiers stationed in Vietnam. This conception of wholesome, all-American beauty and sexuality acted out by largely unknown models reminded young soldiers of the women they left behind, and for whom they were fighting — and could, if they survived, imagine returning to.

The centerfold and other visual features in the magazine served another, unintentional purpose for American troops in Vietnam.

Playboy’s pictures and often-ribald cartoons conveyed changing social and sexual norms back home.

"Don't call me 'boy'!"

The introduction of women of color in 1964 with China Lee and in 1965 with Jennifer Jackson reflected shifting attitudes regarding race. Many soldiers wrote to both the magazine and the Playmates thanking them for their inclusion in Playboy. Black soldiers, in particular, felt that the inclusion of Ms. Jackson extended the promise of Mr. Hefner’s good life to them. Viewing these images forced all Americans to rethink their definitions of beauty.

Over time, the centerfolds pushed the boundaries of social norms and legal definitions as they featured more nudity, with the inclusion of pubic hair in 1969 and full-frontal nudity in 1972. The Washington Post reported that American prisoners of war were “taken aback” by the nudity in a smuggled Playboy found on their flight home in 1973.

The nudity, sexuality and diversity portrayed in the pictorials represented more permissive attitudes about sex and beauty that the soldiers had missed during their years in captivity.

Playboy’s appeal to the G.I. in Vietnam extended beyond the centerfold. The men really did read it for the articles. The magazine provided regular features, editorials, columns and ads that focused on men’s lifestyle and entertainment, including high fashion, foreign travel, modern architecture, the latest technology and luxury cars. The publication set itself up as a how-to guide for those men hoping to achieve Mr. Hefner’s vision of the good life, regardless of whether they were in San Diego or Saigon.For young men serving in Southeast Asia, whose average age was 19, military service often provided them their first access to disposable income. Soldiers turned to the magazine for advice on what gadgets to buy, the best vehicles and the latest fashions — products they could often then buy at one of Vietnam’s enormous on-base exchanges, sprawling shopping centers to rival anything back home.The magazine’s advice feature, “The Playboy Advisor,” encouraged men to ask questions on all manner of topics, from the best liquor to stock at home to bedroom advice to adjusting to civilian life. Troops found Playboy a useful tool in figuring out their roles in the consumer-oriented landscape they were now able to join because of the mobility and income their military service provided them.The content moved beyond lifestyle and entertainment as the editorial mission of the magazine evolved. By the 1960s, Playboy included hard-hitting features on important social, cultural and political issues confronting the United States, often written by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists, government and military leaders and top literary figures. The magazine took on topics like feminism, abortion, gay rights, race, economic issues, the counterculture movement and mass incarceration — something soldiers couldn’t get from Stars and Stripes. It offered exhaustive interviews with everyone from Malcolm X to the American Nazi leader George Lincoln Rockwell, exposing young G.I.s to arguments and ideas about race and African-American equality they might not have been introduced to in their hometowns. Service in Vietnam put many soldiers in direct contact with diverse races and cultures, and Playboy presented them new ideas and arguments regarding those social and cultural issues.As early as 1965, Playboy began running articles about the Vietnam War, with an editorial position that expressed reservations about the escalating conflict. The editors were smart about it, of course: Their stance may have been critical of the president, the administration, the military leaders and the strategy, but they made sure the contributors made every effort to stay supportive of the soldiers. In 1967, troops read the liberal economist John Kenneth Galbraith arguing that “no part of the original justification” for the war “remains intact,” as he dismantled the idea of monolithic Communism and other Cold War justifications for war. But that was different from attacking the troops themselves. In 1971, the journalist David Halberstam wrote in an article for Playboy that “we admired their bravery and their idealism, their courage and dedication in the face of endless problems. We believed that they represented the best of American society.” Troops in Vietnam could turn to Playboy for coverage of their own war without fearing criticism of themselves.Playboy was also useful as a forum for the men engaged in the fighting. The publication was unique in its number of interactive features. Soldiers wrote into sections like “Dear Playboy” for advice and with reactions to articles. But those correspondents also freely described their wartime experiences and concerns. They often described what they saw as unfair treatment by the military, discussed their difficulty in transitioning back to civilian society or thanked the magazine for helping them through their time in-country. In 1973, one soldier, R. K. Redini of Chicago, wrote to Playboy about his return home. “One of the things that made my Vietnam tour endurable was seeing Playboy every month,” he said. “It sure helped all of us forget our problems — for a little while, anyway. I thank you not only for myself but also for the thousands of other guys who find a lot of pleasure in your magazine.”In “The Playboy Forum,” another reader-response section, many wrote in addressing specific aspects of Hefner’s lengthy editorial series “The Playboy Philosophy,” including drugs, race and homosexuality in the military. The forum format allowed those who served in Vietnam to reach out not just to other soldiers, but also to the public, providing them a safe space to voice their opinions and criticisms of their service. “Traditionally, a soldier with a gripe is advised by friends to tell it to the chaplain, take it to the inspector general or write to his congressman,” a soldier wrote. “Now, probably because of letters about military injustice in The Playboy Forum, another court of last resort has been added to the list.”Playboy magazine’s significance to the soldiers in Vietnam spread far beyond the foldout Playmate. Troops appropriated the magazine’s bunny mascot and the company’s logo, painting it on planes, helicopters and tanks. They incorporated the logo into patches and “playboy” into call signs and unit nicknames. Adopting the symbol of Playboy was a small rebellion to the conformity of military life and a testament to the impact of the magazine on soldiers’ lives and morale.

And the magazine returned the favor. Long after the war ended, it funded documentaries on the war, Agent Orange research and post-traumatic stress disorder studies. It is a commitment that testifies to this enduring relationship between the publication and the soldier, and reveals how the magazine is a surprising legacy of one of America’s longest wars.

Goodbye . . .

The Letter by The Box Tops (1967; No. 1 Billboard Hot 100) was popular with American troops, for obvious reasons. Mail call was a sacred ritual in Vietnam and this song captured its importance lyrically and musically. Didn’t hurt that it spoke of “getting a ticket for an airplane” and “going home” because “my baby just wrote me a letter.” Nothing kept guys going more than love letters from home — and the dream of getting back to their beloved.

The reality of this dream, and the fantasy version of the Playboy centrefold "at home" connect in the imagery, but only to be disconnected, and amplify aspirations toward an unfulfillable "American dream". The commodification and objectification of this "sexual revolution" might be seen to begin on boarding a flight.

Coffee, Tea or Me?

The steamy stories of Coffee, Tea or Me? along with Trudy Baker and Rachel Jones were the brainchild of Donald Bain, who started writing in the mid-‘60s, often as a ghostwriter.

Bain, whose day job was writing PR for American Airlines, was set up with two flight attendants who thought they might have some salacious stories to tell. Bain was underwhelmed by their tales, but he believed in the idea of a flight attendant tell-all, so he just went ahead and wrote it himself. The two original stewardesses, whose names weren't Trudy and Rachel, went on the road to promote the book claimed it as their own real memoir.

PSA Keeps The Hemline Up

Air stewardesses in the 50s and 60s had to be single, under 29, weigh less than 135lbs, "smile like they mean it" - and would be fired on the spot if they married or got pregnant.

The Americanisation of the World . . .

Trains and boats . . .

Transportation is civilisation . . .

. . . and the arrival of Hugh Hefner's Playboy Bunnies in 1966 at London Heathrow airport was a moment and sign of (a semiological matrix) the times. In 2017 the BBC looked back to these times, prompted by the death of Hugh Hefner at the age of 91.

Emma Thelwell reports for BBC News on 28 September:

2017English girls were flown to the US to train as Playboy bunny waitresses and croupiers.

A select few were invited to do magazine shoots and to stay at the infamous Playboy mansion in Los Angeles.Carol Needham, 57, from Surrey, was one of them."I lived there for about four months because they were waiting to shoot my centrefold," she told the BBC."Looking back it was quite an amazing thing to have happened, I think only a few from England have been a centrefold."Ms Needham said Hefner was "a very clever man" to publish such a controversial magazine at that time.She added: "Actually believe it or not he was quite a shy man - he was quiet."They [people] probably think he was quite flamboyant because of the image, the parties. But he was actually a gentleman, he was kind, and he was a nice man."

The UK's capital was a natural fit for Hefner's bunnies.

Britain was more susceptible to Americanisation than other places in Europe, social historian Dr Laura Carter explained."Since the 19th Century, London has been an experimental urban place where the most extreme things could happen - a hotbed of sexual transgression," Dr Carter said."Although for the ordinary young woman living in say Bradford or Bristol in the 60s, it was still fairly conservative."The 1960s marked the beginning of a 20 year period that would see women living more socially and sexually freely, Dr Carter added.

Male dominated British media fall in love . . .

Hefner went on to open two more clubs in the UK - in Portsmouth and Manchester - raking in bumper profits for the parent company.

He also acquired the Clermont Club in London's Berkeley Square - the exclusive club above Annabel's nightclub - whose members once included Lord Lucan and James Bond author Ian Fleming.But in 1981, amid a government crackdown on the gaming industry, Playboy's London casinos lost their licences, slashing the group's income and contributing to a major decline in Hefner's fortunes.For 30 years the Playboy clubs were considered part of the UK's social history. The flagship Park Lane club has long-since been replaced by a hotel.But in 2011, the bunnies were back.Hefner opened a new Playboy club in London's Mayfair, recruiting 80 bunnies and signing up about 850 new members, including 350 women and stars including Elton John's partner David Furnish and the model Yasmin Le Bon.

Not all were so welcoming. Angry protestors gathered outside arguing that bunnies championed the use of women as sex objects.

Feminist writer Laurie Penny criticised the reopening, calling Playboy "wilting, impotent and dated".

At the time, Hefner told the BBC:

"Well for some people's tastes, freedom has its downsides."But he argued:

"Far more damage is done by the repression of sexuality, historically, than the liberation."Re:LODE Radio considers that Hugh Hefner was a businessman first and an ersatz philosopher second. Personal freedom and making money? It's the American way and ideology rules!

A wonderful sorority . . .

Down the Rabbit Hole: Curious Adventures and Cautionary Tales of a Former Playboy Bunny is a New York Times bestselling memoir by ex-Playboy Bunny Holly Madison that's an exposé that according to the New York Times Inside the List :

"paints a fairly tawdry picture of Madison’s years as Hugh Hefner’s girlfriend — or, more accurately, as the “No. 1 girlfriend” in a volatile harem rife with infighting, sexual competition and petty jealousies over money and favors. (I told you it was tawdry.)

Gregory Cowles goes on to say that:

Hef has accused Madison of “rewriting history,” a claim she shrugged off in a recent interview with The Associated Press: “He doesn’t have any mental or emotional power over me anymore,” she said. “He’s somebody that I look back on as somebody who treated me really poorly, who I tried to convince myself was a great person but I don’t think is. And I don’t want negative, toxic people in my life anymore.” All of this is a good excuse, if you needed one, to dig up a copy of Gloria Steinem’s 1963 exposé of the Playboy Club in New York City, where she briefly assumed a false name and went undercover in the standard satin costume, complete with ears and a rabbit tail. “A middle-aged man in a private guard’s uniform grinned and beckoned,” Steinem wrote. “ ‘Here bunny, bunny, bunny,’ he said, and jerked his thumb toward the glass door on the left. ‘Interviews downstairs in the Playmate Bar.’ ” Madison might recognize the world Steinem was writing about, even if it had less silicone than she’s used to; evidently, the bunnies of Steinem’s era padded their bosoms with plastic dry-cleaning bags.

This image of Gloria Steinem in her Bunny outfit and a more recent photo of the American feminist journalist and social political activist, can be found on the Guardian webpage from May 2013 in an Op ed piece marking the fifty year anniversary of her ground breaking article.

The Brand and its LOGO

The logo was the work of Playboy’s Art Director Art Paul. After the success of Issue #1, Bunny HQ jumped on an idea and devised a plan for a logo to brand the product. The original vision, according to Paul, was for something that was “frisky and playful…but had a humorous sexual connotation.”

Hefner revealed a raw take on the idea saying that in America, the rabbit, or bunny has a sexual meaning. He liked the concept because he viewed rabbits and bunnies as “shy, vivacious, jumping – sexy.”

In other words: "fucking like rabbits!"

The Playboy logo itself first appeared in Issue #2. A running joke in the Editorial Department was to ‘hide’ the rabbit logo somewhere on the front cover, turning each monthly issue of the magazine into an unofficial puzzle with the Rabbit logo being well disguised with the creative placement of props and the front cover photographic design elements.

The Playboy LOGO and the "brand", has turned out to be Playboy's biggest asset.

NO LOGO

When it comes to globalisation, advertising and the "brand", it is but a part of the capitalist Americanisation of the World.

No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies is a book by the Canadian author Naomi Klein. First published in December 1999, shortly after the 1999 WTO Ministerial Conference protests in Seattle had generated media attention around such issues, it became one of the most influential books about the alter-globalization movement and an international bestseller. While the book focuses on branding and often makes connections with the anti-globalization movement, globalization appears frequently as a recurring theme, but Klein rarely addresses the topic of globalization itself, and when she does, it is usually indirectly. She goes on to discuss globalization in much greater detail in her book, Fences and Windows (2002).

Throughout the four parts of NO LOGO ("No Space", "No Choice", "No Jobs", and "No Logo"), Klein writes about issues such as sweatshops in the Americas and Asia, culture jamming, corporate censorship, and Reclaim the Streets.

Klein pays special attention to the usual suspects, to the deeds and misdeeds of Nike, The Gap, McDonald's, Shell, and Microsoft – and of their lawyers, contractors, and advertising agencies. Many of the ideas in Klein's book derive from the influence of the Situationists, an art/political group founded in the late 1950s.

The fall of Playboy . . .

One of the Playboy Interviews mentioned in the Insider News article has a wider relevance for Re:LODE Radio in that it includes:

"a candid conversation with the high priest of pop cult and metaphysician of media Marshall McLuhan"

The Interview

HOT & COOL

In this interview for Playboy Magazine Marshall McLuhan talks about media (McLuhan introduced this term we now use everyday) in terms of a "fallacy" (fallacy as concept NOT as a falsehood), that a medium such as photography, which is a high definition medium, is a "HOT" medium, while TV, as a low definition medium is a "COOL" medium.

So COOL . . .

Explaining his "fallacy" this is what McLuhan says in response to the Playboy interviewer's question:Interviewer: But isn’t television itself a primarily visual medium?McLuhan: No, it’s quite the opposite, although the idea that TV is a visual extension is an understandable mistake. Unlike film or photograph, television is primarily an extension of the sense of touch rather than of sight, and it is the tactile sense that demands the greatest interplay of all the senses. The secret of TV’s tactile power is that the video image is one of low intensity or definition and thus, unlike either photograph or film, offers no detailed information about specific objects but instead involves the active participation of the viewer. The TV image is a mosaic mesh not only of horizontal lines but of millions of tiny dots, of which the viewer is physiologically able to pick up only 50 or 60 from which he shapes the image; thus he is constantly filling in vague and blurry images, bringing himself into in-depth involvement with the screen and acting out a constant creative dialog with the iconoscope. The contours of the resultant cartoonlike image are fleshed out within the imagination of the viewer, which necessitates great personal involvement and participation; the viewer, in fact, becomes the screen, whereas in film he becomes the camera. By requiring us to constantly fill in the spaces of the mosaic mesh, the iconoscope is tattooing its message directly on our skins. Each viewer is thus an unconscious pointillist painter like Seurat, limning new shapes and images as the iconoscope washes over his entire body.

Since the point of focus for a TV set is the viewer, television is Orientalizing us by causing us all to begin to look within ourselves. The essence of TV viewing is, in short, intense participation and low definition – what I call a “cool” experience, as opposed to an essentially “hot,” or high definition - low participation, medium like radio.

He continues with his understanding of the impact of TV on those growing up in its illuminating effects later in the interview saying:

In the absence of such elementary awareness, I’m afraid that the television child has no future in our schools. You must remember that the TV child has been relentlessly exposed to all the “adult” news of the modern world — war, racial discrimination, rioting, crime, inflation, sexual revolution. The war in Vietnam has written its bloody message on his skin; he has witnessed the assassinations and funerals of the nation’s leaders; he’s been orbited through the TV screen into the astronaut’s dance in space, been inundated by information transmitted via radio, telephone, films, recordings and other people. His parents plopped him down in front of a TV set at the age of two to tranquilize him, and by the time he enters kindergarten, he’s clocked as much as 4000 hours of television. As an IBM executive told me, “My children had lived several lifetimes compared to their grandparents when they began grade one.”Later, McLuhan says, explaining something of his intellectual journey and of his methodology says:

As someone committed to literature and the traditions of literacy, I began to study the new environment that imperiled literary values, and I soon realized that they could not be dismissed by moral outrage or pious indignation. Study showed that a totally new approach was required, both to save what deserved saving in our Western heritage and to help man adopt a new survival strategy. I adapted some of this new approach in The Mechanical Bride by attempting to immerse myself in the advertising media in order to apprehend its impact on man, but even there some of my old literate “point of view” bias crept in. The book, in any case, appeared just as television was making all its major points irrelevant.

The role of the artist's creative activity as a "probe"!

For McLuhan the role of the artist in society, exploring what is actually "happening", is a crucial nexus in the understanding of what's going on, as it is going on in real time. Five years after the publication of McLuhan's The Mechanical Bride a group of friends and artists in London were putting together what today would be described as an "installation" for the exhibition This Is Tomorrow. Richard Hamilton and his friends John McHale and John Voelcker had collaborated to create a room that became the best-known part of the exhibition.

This image, a collage, now well known as Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing? was created in 1956 for the catalogue of the exhibition, where it was reproduced in black and white. Richard Hamilton, who is credited as being the artist responsible for this image, along with John McHale and John Voelcker, were at this time members of the Independent Group, where the term "pop art" was first used in IG discussions by mid-1955. The future, it seems for these Anglophone innovators, was an overlapping of a technological transformation of culture and society with the Americanisation of the World.

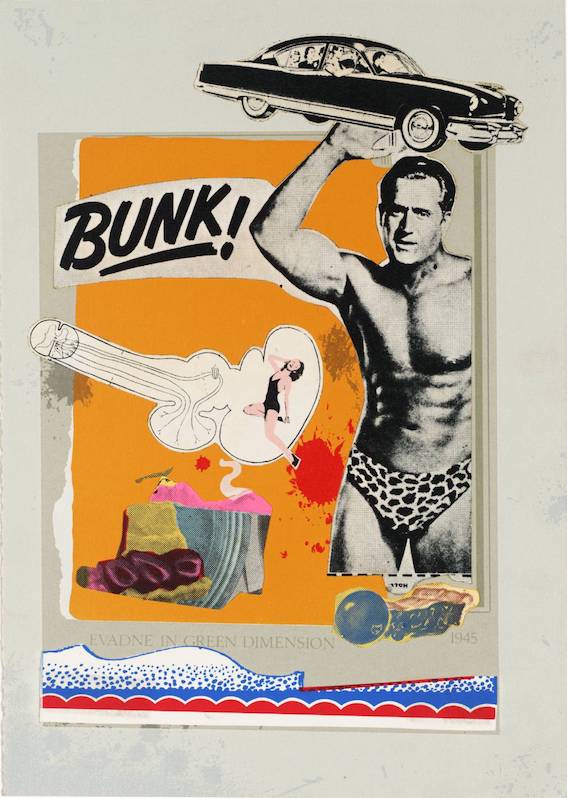

BUNK!

The Independent Group had its first meeting in April 1952, which consisted of artist and sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi feeding a mass of colourful images from American magazines through an epidiascope. These images, composed of advertising, comic strips and assorted graphics, were collected when Paolozzi was resident in Paris from 1947-49. Much of the material was assembled as scrapbook collages and formed the basis of his BUNK! series of screenprints (1972) and the Krazy Kat Archives now held at the V & A Museum, London.

In fact, Paolozzi's seminal 1947 collage I was a Rich Man's Plaything was the first such "found object" material to contain the word ″pop″ and is considered the initial standard bearer of “Pop Art”. The rest of the first Independent Group session concentrated on philosophy and technology during September 1952 to June 1953, chaired by design historian, Reyner Banham.

The IG chose a non-hierarchical approach to cultural production and knowledge

Key members included Paolozzi, the artist Richard Hamilton, surrealist and magazine art director Toni del Renzio, sculptor William Turnbull, the photographer Nigel Henderson and fine artist John McHale, along with the art critic Lawrence Alloway.

Hamilton's early work was much influenced by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson's 1917 text On Growth and Form providing for the development of a non-Aristotelian and non-hierarchical approach to all kinds of phenomena, whether "natural" or "cultural". In 1951, Hamilton staged an exhibition called Growth and Form at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. A pioneering form of installation art, it featured scientific models, diagrams and photographs presented as a unified artwork. Assembling and disassembling the products of popular culture, and considering on the same level, and equal terms as the products of a so-called "high culture", created the conditions for a new kind of post-surrealist art, "pop art".

In the corner of yesterday's "home", pasted behind the "burlesque" woman of the house, is what turned out to be the implosive and de-centred "centre of attention".

It was TV that brought the Vietnam War into the American suburban home, exposing the brutal realities of WAR as something RAW, and at the same time completely CRAZY, more akin to the Theatre of the Absurd and Antonin Artaud's Theatre of Cruelty.

Bringing it all home . . .

This report, part of the CBS coverage of the Vietnam War, brings it all home, and for the TV generation this home is no longer a place of refuge, and the possibility of alternative becomes the focus of countercultural rejection and resistance, as acted out here in these clips from the 1970 film by Michelangelo Antonioni, Zabriskie Point.

BLAST . . .

No wonder an "un-American" counterculture burst out from "underground" and upon a scene from a "Soap Opera" or "Mini-series" world, where the fake and ideologically constructed so-called "family values", instrumental in the oppressive force behind that ideology, were challenged, and, lo and behold, began to crumble.

New circles of HELL?

The American dream is also its opposite, an American nightmare. Beneath the idyll of modern life new circles were being carved into the republic of HELL.

The scene with the Playboy Playmates in the film Apocalypse Now is an exotic apparition, an artificial and electric brightness set against the night, a scene of "modern civilisation" amidst the many other scenes of a lush landscape, haunted by random acts of violence, in a ponderous journey through zones of darkness. But nevertheless the Playboy Playmates scene is one among many new circles of a modern . . .

. . . Inferno.

A Divine Comedy?

The Divine Comedy is a lengthy Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed in 1320, a year before his death in 1321. It is NOT written in LATIN, but in the common Tuscan language spoken in the city of Florence, and consequently regarded widely to be the pre-eminent work in what was to become Italian literature and one of the greatest works of world literature.

The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval world-view as it had developed in the Western Church by the 14th century. It helped establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language. It is divided into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.The narrative takes as its literal subject the state of the soul after death and presents an image of divine justice meted out as due punishment or reward, and describes Dante's travels through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise or Heaven. Allegorically the poem represents the soul's journey towards God, beginning with the recognition and rejection of sin (Inferno), followed by the penitent Christian life (Purgatorio), which is then followed by the soul's ascent to God (Paradiso).

The Inferno describes Dante's journey through Hell, guided by the ancient Roman poet Virgil. In the poem, Hell is depicted as nine concentric circles of torment located within the Earth; it is the;

"realm ... of those who have rejected spiritual values by yielding to bestial appetites or violence, or by perverting their human intellect to fraud or malice against their fellowmen".

Canto I

The poem begins on the night of Maundy Thursday on March 24 (or April 7), AD 1300, shortly before dawn of Good Friday. The narrator, Dante himself, is thirty-five years old, and thus "midway in the journey of our life". The poet finds himself lost in a dark wood (selva oscura), astray from the "straight way" also translatable as the "right way" to salvation. He sets out to climb directly up a small mountain, but his way is blocked by three beasts he cannot evade: a lonza ("leopard" or "leopon"), a leone (lion), and a lupa (she-wolf). However, Dante is rescued by a figure who announces that he was born sub Iulio (i.e. in the time of Julius Caesar) and lived under Augustus: it is the shade of the Roman poet Virgil, author of the Aeneid, a Latin epic.

Canto II

On the evening of Good Friday, Dante hesitates as he follows Virgil; Virgil explains that he has been sent by Beatrice, the symbol of Divine Love.

A version of "courtly love", and a fantasy and projection upon the "love object/subject", and all from a safe distance . . .

This is a detail of Dante and Beatrice, a painting dated 1883 by the artist Henry Holiday and is well known and admired by visitors to the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, England. The moment depicted in the painting is based on Dante's 1294 autobiographical work La Vita Nuova which describes his love for Beatrice Portinari.

According to the autobiographic La Vita Nuova, Beatrice and Dante met only twice during their lives. Following their first meeting, Dante was so enthralled by Beatrice that he later wrote in La Vita Nuova: "Ecce Deus fortior me, qui veniens dominabitur michi" ("Behold, a deity stronger than I; who coming, shall rule over me").

Dante - the poet and stalker?

Indeed, Dante frequented parts of Florence, his home city, where he thought he might catch even a glimpse of her. As he did so, he made great efforts to ensure his thoughts of Beatrice remained private, even writing poetry for another lady, so as to use her as a "screen for the truth". Dante's courtly love for Beatrice continued for nine years, before the pair finally met again. This meeting occurred in a street of Florence, which she walked along dressed in white and accompanied by two older women. She turned and greeted him, her salutation filling him with such joy that he retreated to his room to think about her. In doing so, he fell asleep, and had a dream which would become the subject of the first sonnet in La Vita Nuova.

In the second Canto Virgil explains to Dante that Beatrice had been moved to aid Dante by the Virgin Mary (symbolic of compassion) and Saint Lucia (symbolic of illuminating Grace). Rachel, symbolic of the contemplative life, also appears in the heavenly scene recounted by Virgil. The two of them then begin their journey to the underworld.

Canto III

In this drawing and watercolour by William Blake, Dante passes through the gate of Hell, which bears an inscription ending with the famous phrase "Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch'intrate", most frequently translated as:

"Abandon all hope, ye who enter here."

Dante and his guide hear the anguished screams of the Uncommitted. These are the souls of people who in life took no sides; the opportunists who were for neither good nor evil, but instead were merely concerned with themselves.

After passing through the vestibule, Dante and Virgil reach the ferry that will take them across the river Acheron and to Hell proper. The ferry is piloted by Charon, who does not want to let Dante enter, for he is a living being. Virgil forces Charon to take him by declaring, Vuolsi così colà dove si puote / ciò che si vuole ("It is so willed there where is power to do / That which is willed"), referring to the fact that Dante is on his journey on divine grounds.

Hell has an Aristotelian hierarchy

Dante's Hell is structurally based on the ideas of Aristotle, but with "certain Christian symbolisms, exceptions, and misconstructions of Aristotle's text", and a further supplement from Cicero's De Officiis. Virgil reminds Dante (the character) of “Those pages where the Ethics tells of three/Conditions contrary to Heaven’s will and rule/Incontinence, vice, and brute bestiality”. Cicero for his part had divided sins between Violence and Fraud. By conflating Cicero's violence with Aristotle's bestiality, and his fraud with malice or vice, Dante the poet obtained three major categories of sin, as symbolized by the three beasts that Dante encounters in Canto I: these are Incontinence, Violence/Bestiality, and Fraud/Malice. Sinners punished for incontinence (also known as wantonness) – the lustful, the gluttonous, the hoarders and wasters, and the wrathful and sullen – all demonstrated weakness in controlling their appetites, desires, and natural urges; according to Aristotle's Ethics, incontinence is less condemnable than malice or bestiality, and therefore these sinners are located in four circles of Upper Hell (Circles 2–5). These sinners endure lesser torments than do those consigned to Lower Hell, located within the walls of the City of Dis, for committing acts of violence and fraud – the latter of which involves, as Dorothy L. Sayers writes, "abuse of the specifically human faculty of reason". The deeper levels are organized into one circle for violence (Circle 7) and two circles for fraud (Circles 8 and 9). As a Christian, Dante adds Circle 1 (Limbo) to Upper Hell and Circle 6 (Heresy) to Lower Hell, making 9 Circles in total; incorporating the Vestibule of the Futile, this leads to Hell containing 10 main divisions. This "9+1=10" structure is also found within the Purgatorio and Paradiso. Lower Hell is further subdivided: Circle 7 (Violence) is divided into three rings, Circle 8 (Fraud) is divided into ten bolge, and Circle 9 (Treachery) is divided into four regions. Thus, Hell contains, in total, 24 divisions.

Nine circles of Hell . . .

Virgil proceeds to guide Dante through the nine circles of Hell. The circles are concentric, representing a gradual increase in wickedness, and culminating at the centre of the earth, where Satan is held in bondage. The sinners of each circle are punished for eternity in a fashion fitting their crimes: each punishment is a contrapasso, a symbolic instance of poetic justice. The representation of this "poetic justice" has, to modern eyes, a quality that may well be justifiably and recognisably described as sadomasochistic.

Whipping girl and whipping boy?

When it comes to an example of both the fantastic and American exceptionalism, you can't beat the creation of Superman by Joe Shuster along with the comic strip writer Jerry Siegel. Shuster also created a new kind of Hell with Nights of Horror, an American series of fetish comic books, created in 1954 by publisher Malcla.

Crime, punishment and misogyny?

What did she do to deserve this?

Just because she is female?

For Dante, and his readers, there is a degree of personal gratification and release that comes from the infliction of physical pain or humiliation upon those considered an enemy, lumping them in with other "wicked" characters who receive due and "poetic justice". In the Fifth Circle of Hell, reserved for the wrathful, Dante and Virgil find Filippo Argenti. The scene is a bizarrely personal one, and it shows that some people really will write their enemies into the master work. Argenti was one of Dante’s political rivals, but the animosity between the characters has led historians to suspect there was something more behind his reason for this hatred. Some suggest that Argenti’s family seized Dante’s property when he was exiled from Florence or that there had been a physical altercation between the two.

Dante and Virgil visit the first two bolge of the Eighth Circle

In this illustration of Dante's Inferno by Sandro Botticelli we are shown the first two bolges of the Eighth Circle of Hell.

In Dante Alighieri's Inferno, part of the Divine Comedy, Malebolge is the eighth circle of Hell. Roughly translated from Italian, Malebolge means "evil ditches". Malebolge is a large, funnel-shaped cavern, itself divided into ten concentric circular trenches or ditches.

Each trench is called a bolgia (Italian for "pouch" or "ditch"). Long causeway bridges run from the outer circumference of Malebolge to its center, pictured as spokes on a wheel. At the center of Malebolge is the ninth and final circle of hell.

Canto XVIII

Dante now finds himself in the Eighth Circle: the upper half of the Hell of the Fraudulent and Malicious. The Eighth Circle is a large funnel of stone shaped like an amphitheatre around which run a series of ten deep, narrow, concentric ditches or trenches. Within these ditches are punished those guilty of Simple Fraud. From the foot of the Great Cliff to the Well (which forms the neck of the funnel) are large spurs of rock, like umbrella ribs or spokes, which serve as bridges over the ten ditches. Dorothy L. Sayers writes that the Malebolge is, "the image of the City in corruption: the progressive disintegration of every social relationship, personal and public. Sexuality, ecclesiastical and civil office, language, ownership, counsel, authority, psychic influence, and material interdependence – all the media of the community's interchange are perverted and falsified".In Bolgia 1 Dante places the Panderers and seducers:

These sinners make two files, one along either bank of the ditch, and march quickly in opposite directions while being whipped by horned demons for eternity. They "deliberately exploited the passions of others and so drove them to serve their own interests, are themselves driven and scourged". In the group of panderers, the poets notice Venedico Caccianemico, a Bolognese Guelph who sold his own sister Ghisola to the Marchese d'Este. In the group of seducers, Virgil points out Jason, the Greek hero who led the Argonauts to fetch the Golden Fleece from Aeëtes, King of Colchis. He gained the help of the king's daughter, Medea, by seducing and marrying her only to later desert her for Creusa. Jason had previously seduced Hypsipyle when the Argonauts landed at Lemnos on their way to Colchis, but "abandoned her, alone and pregnant".In Bolgia 2 Dante places the Flatterers:

These also exploited other people, this time abusing and corrupting language to play upon others' desires and fears. They are steeped in excrement (representative of the false flatteries they told on earth) as they howl and fight amongst themselves.

A Comedy?

The work was originally simply titled Comedìa; so also in the first printed edition, published in 1472), Tuscan for "Comedy", later adjusted to the modern Italian Commedia. The adjective Divina was added by Giovanni Boccaccio, due to its subject matter and lofty style, and the first edition to name the poem Divina Comedia in the title was that of the Venetian humanist Lodovico Dolce, published in 1555 by Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari.

Erich Auerbach has said that Dante was the first writer to depict human beings as the products of a specific time, place and circumstance as opposed to mythic archetypes or a collection of vices and virtues; this along with the fully imagined world of the Divine Comedy, different from our own present, but fully visualized, suggests that the Divine Comedy could be said to have inaugurated modern fiction.

Fact and fiction. The innocent and the guilty?

This video montage juxtaposes the filmed CBS News report from the Vietnam War, a factual documentation, with scenes from two film versions of The Stepford Wives, a 1972 satirical novel by Ira Levin.

The CBS News report shows us a new ditch in an ongoing modern tragedy. The story of a young mother in the fictional narrative is another "bolgia". This "comedy" concerns Joanna Eberhart, a photographer and young mother who suspects the submissive housewives in her new idyllic Connecticut neighborhood may be robots created by their husbands. At the end of the 1975 film version of The Stepford Wives Joanna is eventually confronted by her own unfinished robot replica, and shocked when she witnesses its soulless, empty eyes. The Joanna-replica brandishes a nylon stocking and smilingly approaches Joanna to strangle her. Some time later, the artificial "Joanna" placidly peruses the local supermarket amongst the other "wives," all glamorously dressed. As they make their way through the store, they each vacantly greet one another. The android "Joanna" now has the normal-looking eyes of her original human counterpart.

In both fact and fiction, it's the innocent that are punished in . . .

The video montage then cuts to a performance by the UK group The Animals of a song that has resonated with veterans of the Vietnam War who found themselves stuck in a Hell of the U.S. governments making:

We Gotta Get Out of This Place

In their 2015 book We Gotta Get Out of This Place, Doug Bradley and Craig Werner place popular music at the heart of the American experience in Vietnam. They explore how and why U.S. troops turned to music as a way of connecting to each other and the World back home and of coping with the complexities of the war they had been sent to fight. They also demonstrate that music was important for every group of Vietnam veterans - black and white, Latino and Native American, men and women, officers and "grunts" - whose personal reflections drive the book's narrative. Many of the voices are those of ordinary soldiers, airmen, seamen, and marines. But there are also "solo" pieces by veterans whose writings have shaped our understanding of the war - Karl Marlantes, Alfredo Vea, Yusef Komunyakaa, Bill Ehrhart, Arthur Flowers - as well as songwriters and performers whose music influenced soldiers' lives, including Eric Burdon, James Brown, Bruce Springsteen, Country Joe McDonald, and John Fogerty. Together their testimony taps into memories -- individual and cultural - that capture a central if often overlooked component of the American war in Vietnam.

Of their project Doug Bradley says in an article, that first appeared on the PBS site Next Avenue. The Vietnam War, a 10-part Emmy-nominated PBS series by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick:I first became a soldier in a war zone on Veterans Day (Nov. 11) 1970. It’s an irony I’ve wrestled with for 45 years, due in part to the precise timing of U. S. Army tours of duty in Vietnam, which meant that Uncle Sam would send me back home exactly 365 days later — on Nov. 11, 1971.Needless to say, the date is etched in my mind and will always be. It’s personal, of course, but in a way it’s lyrical, too. I say that because my earliest Vietnam memories aren’t about guns and bullets, but rather about music. As my fellow “newbies” and I were being transported from Tan Son Nhut Air Force Base to the Army’s 90th Replacement Battalion at Long Binh, I vividly recall hearing Smokey Robinson and The Miracles singing “Tears of a Clown”. That pop song was blasting from four or five radios some of the guys had, and with the calliope-like rhythm and lines like “it’s only to camouflage my sadness,” I was having a hard time figuring out just where in the hell I was.But I knew one thing for sure. Music was going to get me through my year in Vietnam. Did it ever. In fact, it’s sustained me for the past 45 years, as it has countless other Vietnam veterans.Craig Werner and I discovered the power of music from a decade of interviews with hundreds of Vietnam vets. Our new book, We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War shows how music helped soldiers/veterans connect to each other and to life back home and to cope with the complexities of the war they had been sent to fight.Many of the men and women we interviewed for We Gotta Get Out of This Place had never talked about their Vietnam war experience, even with their spouses and family members. But we found they could talk about a song — “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’”, “My Girl”, “And When I Die”, “Ring of Fire” and scores of others. And the talking helped heal some of the wounds left from the war.When we began our interviews, we planned to organize it into a set of essays focusing on the most frequently mentioned songs, a Vietnam Vets Top 20 if you will, harkening back to the radio countdowns that so many of us grew up listening to.Well, it didn’t take long for us to realize that to do justice to the vets’ diverse, and personal, musical experiences would require something more like a Top 200 — or 2,000! Still, we did find some common ground.

These are the 10 most mentioned songs by the Vietnam vets we interviewed.

Realizing, of course, that every soldier had their own special song that helped bring them home . . .. . . but coming in at No 1 - We Gotta Get Out of This Place by The AnimalsNo one saw this coming. Not the writers of the song — the dynamic Brill Building duo of Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil; not the group who recorded it — The Animals and their iconic lead singer, Eric Burdon; not the 3 million soldiers who fought in Vietnam who placed extra importance on the lyrics. But the fact is that We Gotta Get Out of This Place is regarded by most Vietnam vets as our We Shall Overcome, says Bobbie Keith, an Armed Forces Radio DJ in Vietnam from 1967-69. Or as Leroy Tecube, an Apache infantryman stationed south of Chu Lai in 1968, recalls: “When the chorus began, singing ability didn’t matter; drunk or sober, everyone joined in as loud as he could.” No wonder it became the title of our book!

Following The Animals in this video montage is a clip of the 2004 film version of The Stepford Wives. The clip shows all of the Stepford wives, including Joanna, who is now transformed into a blonde, and all dressed in their Sunday dresses, to go shopping at the grocery store.Just prior to this in this "updated" narrative adaptation of the original satire, a group of the Stepford husbands had cornered Joanna and her husband Walter, and forced them toward the cyborg transformation room where she is to have a microchip implanted in her brain. But before Joanna enters, she makes a final appeal by asking whether the new wives really mean it when they tell their husbands that they love them.

The montage follows on from the grocery store with Joanna and Walter as the guests of honour, as the Stepford elite hosts a formal ball.

A happy ending?

This 2004 remake includes an updated ending, that is ostensibly offering a more progressive conclusion than the bleaker 1975 version.

It turns out that during the festivities of the Stepford ball, Walter slips away returning to the transformation room, where he destroys the software that renders all the Stepford women so submissive and obedient to their husbands. Walter returns to the ball, where the baffled husbands are cornered by their vengeful wives. Walter reveals that Joanna never received the microchip implant because her argument during the struggle had won him over. Out of his love for and loyalty to the human being he married, he joined her plan to infiltrate Stepford, with her pretending to be a cyborg.Six months later, Larry King is interviewing Joanna, Bobbie, and Roger, with Walter also in attendance. They have all met with success; Joanna has made a documentary, Bobbie has written a book of poetry, and Roger broke up with Jerry and won his State Senate seat as an Independent. As King asks about the fate of the other husbands of Stepford, Roger and Bobbie explain that they are still in Stepford, under house arrest, and are being retrained to become better people. The closing scene of the film reveals that the irate wives have taken over Stepford and are forcing their husbands to atone for their crimes by making them do housework and shop for them.

Re:LODE Radio considers this film to be yet another example of the mobilisation of the propaganda machine, with another fairytale ending that presents the ideological version of reality.

Ideology inverts the actuality!

The recent pandemic shows that when it comes to the domestic sphere, economic man goes about his business from home or at work, while domestic woman also works and has to do everything else too, including all the unpaid care roles that keep capitalism viable as a profit oriented systemic system based on inequalities.

This WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM story on a report in November by UN Women found clear evidence that, although both genders have seen their unpaid workloads increase, women are bearing more of the burden than men.

Before the pandemic, women were spending on average three times as many hours on unpaid domestic and caring work - and this contribution was grossly undervalued. The ILO in 2018 reported that the 16 billion hours spent on unpaid caring every day would represent nearly a tenth of the world’s entire economic output if it was paid at a fair rate.

Now a landmark ruling in China which ordered a husband to pay his wife for the housework she had done during their five-year marriage has renewed debate around how we recognize and value unpaid work.Under China’s new marriage law, which came into effect at the start of this year, a clause entitles the party taking on more childcare and domestic duties to ask for compensation during a divorce, a lawyer told the South China Morning Post.In the case in Beijing, the wife was awarded a one-off payment of $7,700 for housework she had done during their marriage.But while it recognized the wife's contribution, the ruling ignited debate online about how we value unpaid work, with some claiming the payment was too little, reported the paper.

The UN Women WOMEN COUNT webpage asks the question:

UNPAID CARE AND DOMESTIC WORK DURING COVID-19

Meanwhile, fiction becomes reality . . .

DEBORA - PREMIUM SEXDOLL

Wine, cheese and BDSM 1,949.00€

Hi guys! My name is Deborah and I’m from Switzerland. I’m 25 years old and love to drink wine and taste different cheeses of the world.

If you like it too, we can spend some good time together. I’m going to tell some more things about me, so you can make up your mind! I live in this little country surrounded by mountains and have a comfortable life. I’m so young and here it’s all so calm that I need some thrilling. That’s why I’m on this website looking for somebody to have fun with. I need to be punished. Do you get me? I lost my virginity when I was 15 so I’m not new in sex. I feel that I did everything I wanted with my boyfriend, but something is missing.

First of all, I like BDSM. If you are not ready for this, do not contact me, please. Boyfriends I’ve had many so I don’t need a loving relationship anymore. You know, just some thrilling. I have played dominatrix, but I prefer to be the submissive one. My dream is to be whipped by a beautiful woman while her husband looks on. I want to be the one for you both. We’d discuss what we are going to do and the codes we’re going to use before our reunion. Anything you want to do with me must be previously accepted by me.

I like it rough, hard, aggressive. I might bite your neck or scratch your back. I prefer to wear my leather rather than being naked. I’d love to see your wife in her leather as well and all the elements you bring for our romantic date. Hope you don’t get scared about my intentions. Life is so short I don’t want to pretend about my desire.

For a commentator on the VPorn blog this new reality is greeted with unabashed enthusiasm:

I don’t know about you, but I find this idea genius. Fucking a human-like doll allows you to do to her pretty much whatever you want, plus, it is not considered cheating. You can do all the things you see pornstars do in all those dirty movies. We have a win-win situation right here. All the dudes out there who don’t want to book a hooker for an hour of mind blowing ramming due to having a loving girl back home, now is your chance. Now is your chance to bang other pussies too without any regret. How cool does that sound?

But seriously, are we starting to live in some sort of a television show. Is this even good for us? I am sure some of the folks will be fully against it while the others fully supportive.Let’s face it, robots are a thing of the future so why not introducing them into the adult entertainment, too. However, you might look a total weirdo, having a silicone love doll at home, but no one will really know if you are spending kinky moments with one if you visit Barcelona’s sex doll brothel.

Are sex dolls the future of prostitution?

This video montage begins with the SEXBOTS that will replace women followed by Joel Golby from VICE visiting the centre of this strange battleground for the future of sexual politics.

Capitalist commodification . . .

There are a number of articles to be found on the Re:LODE A Cargo of Questions blog that address the matter of "clickbait" on the internet, especially in regard to the "use of art", and are particularly relevant at this point in the article.

"clickbait" Alert (Adult Content)

Also, at this juncture, Re:LODE Radio references a Guardian Opinion piece from the Re:LODE A Cargo of Questions article:

"clickbait", Helen of Troy, Marie Antoinette, Sex & the Incel story

This Opinion piece by Rebecca Solnit from 2018 (Sat 12 Nay 2018) has the headline:

A broken idea of sex is flourishing. Blame capitalism

Rebecca Sonit's Opinion piece runs with the subheading:

In this world, women are marketed as toys and trophies. Are we surprised when some men take things literally?Rebecca Solnit writes:

Since the Toronto bloodbath, a lot of pundits have belatedly awoken to the existence of the “incel” (short for involuntary celibate) online subculture and much has been said about it. Too often, it has been treated as some alien, unfamiliar worldview. It’s really just an extreme version of sex under capitalism we’re all familiar with because it’s all around us in everything, everywhere and has been for a very long time. And maybe the problem with sex is capitalism.What’s at the bottom of the incel worldview: sex is a commodity, accumulation of this commodity enhances a man’s status, and every man has a right to accumulation, but women are in some mysterious way obstacles to this, and they are therefore the enemy as well as the commodity. They want high-status women, are furious at their own low status, but don’t question the system that allocates status and commodifies us all in ways that are painful and dehumanizing.Entitlement too plays a role: if you don’t think you’re entitled to sex, you might feel sad or lonely or blue, but not enraged at the people who you think owe you. It’s been noted that some of these men are mentally ill and/or socially marginal, but that seems to make them only more susceptible to online rage and a conventional story taken to extremes. That is, it doesn’t cause this worldview, as this worldview is widespread.Rather, it makes them vulnerable to it; the worldview gives form or direction to that isolation and incapacity. Many of the rest of us have some degree of immunity, thanks to our access to counter-narratives and to loving contact with other human beings, but we are all impacted by this idea that everyone has a market value and this world in which so many of us are marketed as toys and trophies.If you regard women as people endowed with certain inalienable rights, then heterosexual sex – as distinct from rape – has to be something two people do together because both of them want to, but this notion of women as people is apparently baffling or objectionable to hordes of men – not just incels.Women-as-bodies are sex waiting to happen – to men – and women-as-people are annoying gatekeepers getting between men and female bodies, which is why there’s a ton of advice about how to trick or overwhelm the gatekeeper. Not just on incel and pick-up-artist online forums but as jokey stuff in movies. You could go back to Les Liaisons Dangereuses and Casanova’s trophy-taking, too.It goes back before capitalism, really, this dehumanization that makes sex an activity men exact from women who have no say in the situation. The Trojan war begins when Trojan Paris kidnaps Helen and keeps her as a sex slave. During the war to get Helen back, Achilles captures Queen Briseis and keeps her as a sex slave after slaying her husband and brothers (and slaying someone’s whole family is generally pretty anti-aphrodisiac). His comrade in arms Agamemnon has some sex slaves of his own, including the prophetess Cassandra, cursed by Apollo for refusing to have sex with him. Read from the point of view of the women, the Trojan wars resemble Isis among the Yazidi.Feminism and capitalism are at odds, if under the one women are people and under the other they are property. Despite half a century of feminist reform and revolution, sex is still often understood through the models capitalism provides. Sex is a transaction; men’s status is enhanced by racking up transactions, as though they were poker chips.Which is why the basketball star Wilt Chamberlain boasted that he’d had sex with 20,000 women in his 1991 memoir (prompting some to do the math: that would be about 1.4 women per day for 40 years). Talk about primitive accumulation! The president of the United States is someone who has regularly attempted to enhance his status by association with commodified women, and his denigration of other women for not fitting the Playmate/Miss Universe template is also well-known. This is not marginal; it’s central to our culture, and now it’s embodied by the president of our country.Women’s status is ambiguous in relation to sexual experience, or perhaps it’s just wrecked either way: there’s that famous scene in The Breakfast Club in which a female character exclaims, “Well, if you say you haven’t, you’re a prude. If you say you have then you’re a slut. It’s a trap.” Reminiscing about these 1980s teen movies she starred in, Molly Ringwald recently recalled: “It took even longer for me to fully comprehend the scene late in Sixteen Candles, when the dreamboat, Jake, essentially trades his drunk girlfriend, Caroline, to the Geek, to satisfy the latter’s sexual urges, in return for Samantha’s underwear.” The Geek has sex with her while she’s unable to consent, which we now call rape and then called a charming coming-of-age movie.This idea of sex as something men get, often by bullying, badgering, tricking, assaulting, or drugging women is found everywhere. The same week as the Toronto van rampage, Bill Cosby was belatedly found guilty of one of the more than 60 sexual assaults that women have reported. He was accused of giving them pills to render them unconscious or unable to resist. Who wants to have sex with someone who isn’t there? A lot of men, apparently, since date rape drugs are a thing, and so are fraternity-house techniques to get underage women to drink themselves into oblivion, and Brock Turner, known as the Stanford rapist, assaulted a woman who was blotted out by alcohol, inert and unable to resist.Under capitalism, sex might as well be with dead objects, not live collaborators. It is not imagined as something two people do that might be affectionate and playful and collaborative – which casual sex can also be, by the way – but that one person gets. The other person is sometimes hardly recognized as a person. It’s a lonely version of sex. Incels are heterosexual men who see this mechanistic, transactional sex from afar and want it at the same time they rage at people who have it.That women might not want to grow intimate with people who hate them and might want to harm them seems not to have occurred to them as a factor, since they seem bereft of empathy, the capacity to imaginatively enter into what another person is feeling. It hasn’t occurred to a lot of other men either, since shortly after an incel in Toronto was accused of being a mass murderer the sympathy started to pour out for him.At the New York Times, Ross Douthat credited a libertarian with this notion: “If we are concerned about the just distribution of property and money, why do we assume that the desire for some sort of sexual redistribution is inherently ridiculous?” Part of what’s insane here is that neither the conservative Douthat nor libertarians are at all concerned with the just distribution of property and money, which is often referred to as socialism. Until the property is women, apparently. And then they’re happy to contemplate a redistribution that seems to have no more interest in what women want than the warlords dividing up the sex slaves in the Trojan war.Happily someone much smarter took this on before Toronto. In late March, at the London Review of Books, Amia Srinivasan wrote: “It is striking, though unsurprising, that while men tend to respond to sexual marginalisation with a sense of entitlement to women’s bodies, women who experience sexual marginalisation typically respond with talk not of entitlement but empowerment. Or, insofar as they do speak of entitlement, it is entitlement to respect, not to other people’s bodies.”That is, these women who are deemed undesirable question the hierarchy that allots status and sexualization to certain kinds of bodies and denies it to others. They ask that we consider redistributing our values and attention and perhaps even desires. They ask everyone to be kinder and less locked into conventional ideas of who makes a good commodity. They ask us to be less capitalistic.What’s terrifying about incel men is that they seem to think the problem is that they lack sex when, really, what they lack is empathy and compassion and the imagination that goes with those capacities. That’s something money can’t buy and capitalism won’t teach you. The people you love might, but first you have to love them.Rebecca Solnit is a freelance columnist and the author of Men Explain Things to Me.

Welcome to Uncanny Valley

In aesthetics, the uncanny valley is a hypothesized relationship between the degree of an object's resemblance to a human being and the emotional response to such an object. The concept suggests that humanoid objects which imperfectly resemble actual human beings provoke uncanny or strangely familiar feelings of eeriness and revulsion in observers. "Valley" denotes a dip in the human observer's affinity for the replica, a relation that otherwise increases with the replica's human likeness.

Examples can be found in robotics, 3D computer animations, and lifelike dolls. With the increasing prevalence of virtual reality, augmented reality, and photorealistic computer animation, the "valley" has been cited in reaction to the verisimilitude of the creation as it approaches indistinguishability from reality. The uncanny valley hypothesis predicts that an entity appearing almost human will risk eliciting cold, eerie feelings in viewers.

The concept was identified by the robotics professor Masahiro Mori as bukimi no tani genshō (不気味の谷現象) in 1970. The term was first translated as uncanny valley in the 1978 book Robots: Fact, Fiction, and Prediction, written by Jasia Reichardt, thus forging an unintended link to Ernst Jentsch's concept of the uncanny, introduced in a 1906 essay entitled "On the Psychology of the Uncanny". Jentsch's conception was elaborated by Sigmund Freud in a 1919 essay entitled "The Uncanny" ("Das Unheimliche").

Mori's original hypothesis states that as the appearance of a robot is made more human, some observers' emotional response to the robot becomes increasingly positive and empathetic, until it reaches a point beyond which the response quickly becomes strong revulsion. However, as the robot's appearance continues to become less distinguishable from a human being, the emotional response becomes positive once again and approaches human-to-human empathy levels.This area of repulsive response aroused by a robot with appearance and motion between a "barely human" and "fully human" entity is the uncanny valley. The name captures the idea that an almost human-looking robot seems overly "strange" to some human beings, produces a feeling of uncanniness, and thus fails to evoke the empathic response required for productive human–robot interaction.

Soft focus? The glaze and "the gaze"? Sheer ideology!

Soft focus, the veil, the covering, the glamour, hiding a reality, and substituting itself for the reality, has an economic and political aspect, and identified by Roland Barthes when discussing "Ornamental Cookery".

Set in aspic . . .

In Mythologies, a 1957 book by Roland Barthes, consisting of a collection of essays taken from Les Lettres nouvelles, examines the tendency of contemporary social value systems to create modern myths. Barthes also looks at the semiology of the process of myth creation, updating Ferdinand de Saussure's system of sign analysis by adding a second level where signs are elevated to the level of myth. He writes thus on:

"Ornamental Cookery"

The weekly Elle (a real mythological treasure) gives us almost every week a fine colour photograph of a prepared dish: golden partridges studded with cherries, a faintly pink chicken chaudfroid, a mould of crayfish surrounded by their red shells, a frothy charlotte prettified with glacé fruit designs, multicoloured trifle, etc.

The 'substantial' category which prevails in this type of cooking is that of the smooth coating: there is an obvious endeavour to glaze surfaces, to round them off, to bury the food under the even sediment of sauces, creams, icing and jellies. This of course comes from the very finality of the coating, which belongs to a visual category, and cooking according to Elle is meant for the eye alone, since sight is a genteel sense. For there is, in this persistence of glazing, a need for gentility. Elle is a highly valuable journal, from the point of view of legend at least, since its role is to present to its vast public which (market-research tells us) is working-class, the very dream of smartness. Hence a cookery which is based on coatings and alibis, and is for ever trying to extenuate and even to disguise the primary nature of foodstuffs, the brutality of meat or the abruptness of sea- food. A country dish is admitted only as an exception (the good family boiled beef), as the rustic whim of jaded city-dwellers.But above all, coatings prepare and support one of the major developments of genteel cookery: ornamentation. Glazing, in Elle, serves as background for unbridled beautification: chiseled mushrooms, punctuation of cherries, motifs of carved lemon, shavings of truffle, silver pastilles, arabesques of glacé fruit: the underlying coat (and this is why I called it a sediment, since the food itself becomes no more than an indeterminate bed- rock) is intended to be the page on which can be read a whole rococo cookery (there is a partiality for a pinkish colour).Ornamentation proceeds in two contradictory ways, which we shall in a moment see dialectically reconciled: on the one hand, fleeing from nature thanks to a kind of frenzied baroque (sticking shrimps in a lemon, making a chicken look pink, serving grapefruit hot), and on the other, trying to reconstitute it through an incongruous artifice (strewing meringue mushrooms and holly leaves on a traditional log-shaped Christmas cake, replacing the heads of crayfish around the sophisticated bechamel which hides their bodies). It is in fact the same pattern which one finds in the elaboration of petit-bourgeois trinkets (ashtrays in the shape of a saddle, lighters in the shape of a cigarette, terrines in the shape of a hare).This is because here, as in all petit-bourgeois art, the irrepressible tendency towards extreme realism is countered - or balanced – by one of the eternal imperatives of journalism for women's magazines: what is pompously called, at L'Express, having ideas. Cookery in Elle is, in the same way, an 'idea' - cookery. But here inventiveness, confined to a fairy-land reality, must be applied only to garnishings, for the genteel tendency of the magazine precludes it from touching on the real problems concerning food (the real problem is not to have the idea of sticking cherries into a partridge, it is to have the partridge, that is to say, to pay for it).This ornamental cookery is indeed supported by wholly mythical economics. This is an openly dream-like cookery, as proved in fact by the photographs in Elle, which never show the dishes except from a high angle, as objects at once near and inaccessible, whose consumption can perfectly well be accomplished simply by looking. It is, in the fullest meaning of the word, a cuisine of advertisement, totally magical, especially when one remembers that this magazine is widely read in small-income groups. The latter, in fact, explains the former: it is because Elle is addressed to a genuinely working-class public that it is very careful not to take for granted that cooking must be economical. Compare with L'Express, whose exclusively middle-class public enjoys a comfortable purchasing power: its cookery is real, not magical. Elle gives the recipe of fancy partridges, L'Express gives that of salade niçoise. The readers of Elle are entitled only to fiction; one can suggest real dishes to those of L'Express, in the certainty that they will be able to prepare them.

An aesthetic governed by the "diaphanous", a "see through", "sheer ideology" . . .

The girl next door talks dirty . . .

"So... I only told you how I look in my shirt, but, that's just the beginning. I also know that you love it when I talk about my big, juicy breasts. Well, how about we start playing around with the sheer chemise and see how hot my tits will look in it. Hhmm You know, I just hate wearing bras when I'm home. It just feels much better letting my boobs move freely under my clothes when I walk around the house. So... right now, I'm still looking in the mirror and if I just... shake my shoulders a little, like that, my tits look so hot when they wiggle around. Can you picture that? They almost want to slip out of my chemise. See, I'm... still shaking them and they bump into each other, just like that. Hmm, this is fun. Oh... I can even hear them clapping, now. I love to hear that, it's so sexy. Hhmm all that chest meat, just bumping into each other... Can you hear it? What if I move my phone down there . . ."

Reason and philosophy tearing the veil from truth

Enlightenment?

This is a detail from the frontispiece of the Encyclopédie (1772). It was drawn by Charles-Nicolas Cochin and engraved by Bonaventure-Louis Prévost. The work is laden with symbolism: The figure in the centre represents truth—surrounded by bright light (the central symbol of the Enlightenment).

Two other figures on the right, reason and philosophy, are tearing the veil from truth.Re:LODE Radio considers Playboy to reflect aspects of ongoing social change (or turmoil) in capitalist societies, and in its primary influences, patriarchal.

This type of patriarchy and social agenda are more in line with the so-called "freedoms" so beloved of neoliberals, and the dominant version of global capitalism, freedom to express, to choose (but in a market skewed toward the pursuit of private profit), to make money etc. A key promise of the enlightenment was the possibility of "emancipation", but social values shaped by aspirations in a consumer society, also created new "constraints". Wealth and glamour became the goal rather than self actualisation and the emancipatory potential has withered in a cold wind. Meanwhile gendered roles were mobilised and defined by materials such as in these "public information" films. These propaganda efforts sought to promote the commodification of the suburban woman into a "thrifty wife", and co-opt the "family" as the antidote to the spectre of communism "at home".

The woman who runs the home is . . .These obviously propagandistic films run in a seamless sequence in an ongoing production and process of acculturation. Its smoothness, its fairytale attractiveness, enables the efficient internalisation of an oppressive ideology. An ideological programme developed over the previous two hundred years in what we may call "conduct" literature. This literature, often written by men for women to read, and for their "instruction", reinforces the existing and regressive gender definitions of "economic man" and his helpmate, "domestic woman".

The hot wife starter kit

Gender related patterns of power don't shift much, but the terms of the fantasy are increasingly wide open, and freely applied in the retrograde and regressive evolution of things, as in this example of a 2015 conduct book advising readers on how to get:

Your Sexy Back

Dear Overwhelmed and Under-appreciated Wife, it’s hard to be a grownup these days, especially when you’re trying to hold together a home and family, and even more so when you’ve got kids. As women, it’s our nature to put our families before ourselves, and often to our own detriment.

Despite our best intentions, marriage often causes this odd phenomenon I like to call Mrs. Scrunchie-Sweats. Whether you had kids or you just got busy with the daily grind, one day, you look the mirror and you notice something:

Your standards have changed. You’re walking around in the world wearing sweats and a scrunchie. In public. And you’re justifying it to yourself, most likely thinking you’ve got more important things to worry about than the way you look or carry yourself.

Or maybe you’re just not putting yourself together like you used to, and you might even think that’s what you’ve got to deal with when you’re a busy married woman - you’re not the only person you’ve got to worry about, right?

But something inside you feels a little twinge of jealousy every time you see a woman who seems totally put-together. You know the type - she makes “having it all” look like a breeze - and she looks freaking fabulous while she does it.

Discover the closely-guarded secrets of the hottest, most amazingly sexy women in the world- the simple-to-apply principles they use in their day-to-day lives that separate you from the sexy, stylish wife you want to be.

Get an inside look into why The Hot Wife Guide will work for you, and find out how a taking a few minutes for yourself each day can change your entire life. With this free starter kit, you’ll learn some of the great tips from The Hot Wife Guide.

The trophy wife?

The marriage of former Playboy Playmate Anna Nicole Smith to oil billionaire J. Howard Marshall was widely followed by the US mass media as an extreme example of this concept. At the time of their marriage, he was 89 years old and she was 26.The objectification implicit in the notion of the trophy wife, a wife who is regarded as a status symbol for the husband, is not far from the explicit commodification involved in the hotwifing fantasy of a husband showing off and sharing his “hot wife.” The term is misogynist in its use, derogatory or disparaging, implying that the wife has value only in her physical attractiveness, a value that requires substantial expense in maintaining her appearance, and does very little of substance beyond remaining attractive.

Nostalgia as retrogressive

The "retro" appeal of the archive film material of 1950's suburbia in the twenty-first century generates a sense of nostalgia, that enables an invented version of what was a partial reality, get in the way of understanding what the cultural, economic and political shifts actually were in the 1950's and 60's. And this is reflected, perhaps, in the Playboy archive too.

The idea of "the fifties" in America remains as an ideological construct for the present day, and occasionally mobilised to re-shape a shared understanding of a history that's a selective, or false, version of reality.

Sexual and self-actualisation, emancipation and Revolution?

In the context of culture and entertainment rather than history, the director of the American film from 1998, Pleasantville, Gary Ross explained that:

"This movie is about the fact that personal repression gives rise to larger political oppression...That when we're afraid of certain things in ourselves or we're afraid of change, we project those fears on to other things, and a lot of very ugly social situations can develop."