NOT "clickbait" . . .

Wikipedia: Pornography

This page documents some of the discussions the Wikipedia community have had regarding matters related to pornography. While there is no formal policy, the Wikipedia: Profanity guideline has the advice:

"Words and images that would be considered offensive, profane, or obscene by typical Wikipedia readers should be used if and only if their omission would cause the article to be less informative, relevant, or accurate, and no equally suitable alternatives are available. Including information about offensive material is part of Wikipedia's encyclopedic mission; being offensive is not.". . . and so it is with this blog."clickbait" & the use of Art and/or Pornography

Abduction!This image, a painting by Évariste-Vital Luminais is used in an article published by History Ireland, Ireland's History Magazine, in May/June 2009. The title of Luminais' painting is "Norman Pirates in the 9th century". He is best known for works depicting early French history, and so the type of subject matter Luminais chose for his painting, along with many other historical subjects, led to the artist being sometimes called "the painter of the Gauls".

Slave Traders

The article in History Ireland is headlined The Viking slave trade: entrepreneurs or heathen slavers?, and is referenced in a Re:LODE Cargo of Questions page in the Ceatharlach Information Wrap - Arrivals.

The relationship of the LODE Re:LODE project to information remains critical and questioning, hence the requirement to contextualise the presenting of such information and imagery in this way.

For example: It may have some contextual value to access information about the artwork or artist being used as documentation or as an illustration.

Évariste-Vital Luminais

So, this page addresses the use of imagery as "bait" in the particular information environments encountered in the LODE Re:LODE art project under the heading:

"clickbait"

Acceptable versus Unacceptable?

In this article the discussion on Pornography comes before Art - Up Front!

Pornography - the depiction of prostitution

. . . . a street in Rome.Prostitute is derived from the Latin prostituta. Some sources cite the verb as a composition of "pro" meaning "up front" or "forward" and "stituere", defined as "to offer up for sale".

The depiction of slavery . . . at the slave market.

Up front . . .

. . . and from the back

"clickbait"

A new "portmanteau" word from the 1990's, combining "click" on the link, as with hypertext and hyperlinks, with "bait", as in to "entice" or "entrap" our attention whilst browsing on the internet.

Baggage?The word portmanteau was first used in this sense by Lewis Carroll in the book Through the Looking-Glass (1871), in which Humpty Dumpty explains to Alice the coinage of the unusual words in "Jabberwocky", where slithy means "slimy and lithe" and mimsy is "miserable and flimsy". Humpty Dumpty explains to Alice the practice of combining words in various ways:You see it's like a portmanteau—there are two meanings packed up into one word.

In then-contemporary English, a portmanteau was a suitcase that opened into two equal sections.

This kind of imagery is clickbait, and along with our short attention span, there comes a lot of baggage.Hence the need for some kind of annotation on the part of this project for the reproduction of this archival imagery.

Jimmy Wales - Pornographer?

FAKE NEWS!

Art coming up behind Pornography?

"clickbait" & "Classical" subject matter?

Conspiracy, Racism, Pornography, Democracy?

This image of five naked black men and one blonde white woman is a racialised image, and pornographic because it depicts five erect penises.

When it comes to the "paranoid style" in the ongoing and present global culture wars, Gordon Fraser, who argues that conspiracy theories after the middle of the twentieth century proliferated to such a degree that Hofstadter's imagined, rationally liberal audience no longer exists, if it ever existed in the first place, writes his own essay:

Conspiracy, Pornography, Democracy: The Recurrent Aesthetics of the American Illuminati

The Abstract for Gordon Fraser's essay Conspiracy, Pornography, Democracy: The Recurrent Aesthetics of the American Illuminati describes the essay's argument thus:

This essay examines reactionary, countersubversive fictions produced in the context of two conspiracy theories in the United States: the Illuminati crisis (1798–1800) and Pizzagate (2016–17). The author suggests that both cases emblematize a pornotropic aesthetic, a racialized sadomasochism that recurs across United States culture. Building on the work of Hortense Spillers, Alexander Weheliye, Jennifer Christine Nash, and others, this essay argues that observers should understand countersubversive political reaction as an aesthetic project, a pornotropic fantasy that distorts underlying conditions of racial subjection. In the context of a resurgent far right that describes its enemies as “cuckolds” and frequently deploys the tropes of highly racialized pornography, this essay suggests that we might find the deep origins of pornographic, reactionary paranoia in the eighteenth century. It suggests, moreover, that understanding and contesting the underlying conditions of racial subjection require that scholars consider the power of pornotropic, countersubversive aesthetics to bring pleasure, to move people, and to order the world.

It is the organising idea emerging from the work of Hortense Spillers that Re:LODE Radio foregrounds here, the concept of the sexualization of black bodies. In "Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe: An American Grammar Book" Spillers states that the black community is "captive" and treated as a "living laboratory".

In this essay Spillers creates a distinction in the case between "body" and "flesh"

The body, in this case, is representative of the captor whose existence represents that of the free or the "liberated subject-position[s]". "Body" is a discrete entity whereas "flesh" is related to desire, sexualization, and that the flesh is an undistinguished mass of black people; particularly black women.

The massification of black bodies stems back to her point about black people becoming "ungendered". To her, "gendering" took place within domesticity, which gained power through cultural fictions of "the specificity of proper names". While Spillers's explication of the body/flesh binary naturally lends itself towards a discussion of heteronormative gender relations, her reading of the black body as becoming a site of ungendering points to a queering of our understanding of Western domesticity and with it the place of both black men and women in Western society.

In a 2006 interview entitled, "Whatcha Gonna Do?—Revisiting Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe: An American Grammar Book" Spillers was interviewed by Saidiya Hartman, Farah Jasmine Griffin, Jennifer L. Morgan, and Shelly Eversley. In that interview Spillers shares insight into her writing process, and her interviewers collectively elucidate the seismic impact of the essay on the conceptual vocabulary available to subsequent generations of Black Feminist scholars.She states that she wrote "Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe" with a sense of hopelessness. She was in part writing in response to All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave (1982). Spillers was writing to a moment in history where the importance of black women in critical theory was being denied. She wrote with a sense of urgency in order to create a theoretical taxonomy for black women to be studied in the academy.

All the women are white, all the blacks are men, but some of us are brave . . .

. . . is a landmark feminist anthology in Black Women's Studies printed in numerous editions, co-edited by Akasha Gloria Hull, Patricia Bell-Scott, and Barbara Smith.

In Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, Kimberlé Crenshaw begins her argument with a reference to this work. She says:

One of the very few Black women's studies books is entitled All the Women Are White; All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us are Brave. I have chosen this title as a point of departure in my efforts to develop a Black feminist criticism because it sets forth a problematic consequence of the tendency to treat race and gender as mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis.

It was in this 1989 paper that Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality as a way to help explain the oppression of African-American women. Crenshaw's term is now at the forefront of national conversations about racial justice, identity politics, and policing—and over the years has helped shape legal discussions. In her work, Crenshaw discusses Black feminism, arguing that the experience of being a black woman cannot be understood in terms independent of either being black or a woman. Rather, it must include interactions between the two identities, which, she adds, should frequently reinforce one another.In order to show that non-white women have a vastly different experience from white women due to their race and/or class and that their experiences are not easily voiced or amplified, Crenshaw explores two types of male violence against women: domestic violence and rape. Through her analysis of these two forms of male violence against women, Crenshaw says that the experiences of non-white women consist of a combination of both racism and sexism. She says that because non-white women are present within discourses that have been designed to address either race or sex — but not both at the same time — non-white women are marginalized within both of these systems of oppression as a result.In her work, Crenshaw identifies three aspects of intersectionality that affect the visibility of non-white women: structural intersectionality, political intersectionality, and representational intersectionality.

Structural intersectionality deals with how non-white women experience domestic violence and rape in a manner qualitatively different than that of white women. Structural intersectionality is used to describe how different structures work together and create a complex which highlights the differences in the experiences of women of colour with domestic violence and rape. Structural intersectionality entails the ways in which classism, sexism, and racism interlock and oppress women of colour while molding their experiences in different arenas. Crenshaw's analysis of structural intersectionality was used during her field study of battered women. In this study, Crenshaw uses intersectionality to display the multilayered oppressions that women who are victims of domestic violence face.

Political intersectionality examines how laws and policies intended to increase equality have paradoxically decreased the visibility of violence against non-white women. Political intersectionality highlights two conflicting systems in the political arena, which separates women and women of colour into two subordinate groups. The experiences of women of colour differ from those of white women and men of colour due to their race and gender often intersecting. White women suffer from gender bias, and men of colour suffer from racial bias; however, both of their experiences differ from that of women of color, because women of colour experience both racial and gender bias. According to Crenshaw, a political failure of the antiracist and feminist discourses was the exclusion of the intersection of race and gender that places priority on the interest of "people of color" and "women", thus disregarding one while highlighting the other. Political engagement should reflect support of women of colour; a prime example of the exclusion of women of colour that shows the difference in the experiences of white women and women of colour is the women's suffrage march.

Finally, representational intersectionality delves into how pop culture portrayals of non-white women can obscure their own authentic lived experiences. Representational intersectionality advocates for the creation of imagery that is supportive of women of colour. Representational intersectionality condemns sexist and racist marginalization of women of colour in representation. Representational intersectionality also highlights the importance of women of colour having representation in media and contemporary settings.

As in Playboy?

The African American female model featured here as the Playboy Playmate of the Year is Eugena Washington. When it comes to Representational Intersectionality it goes without saying that Eugena Washington has her own voice in sharing her experience of being a professional model in an industry that commodifies the "body" as an image and a "sign".

Her professional "breakthrough" came when Eugena Washington was chosen to be the Playboy Playmate of the Month for December 2015 and Playmate of the Year 2016. She was only the third African American to be so named. She was also the first Playmate of the Year after Playboy eliminated its Centerfold.

In Playboy magazine's post-nude era, she was the first Playmate of the Year, and was the last to be announced by Hugh Hefner at the Playboy Mansion. Previously, back in 2006, her career as a model was launched when Eugena Washington became the second runner-up on America's Next Top Model, Cycle 7.

Q. Was coming third a kind of humiliation? Or, a game plan?

Eugena speaks candidly about her experience on YouTube with Oliver Twix.

Oliver Twixt says:

Watch this video to get the behind the scenes secrets and tea on Cycle 7 of the hit reality tv show 'America's Next Top Model' from fan favorite, Eugena Washington! She reveals how having bad blood with Tyra Banks, even revealing Tyra potentially selecting bad best photos for her to "humble" her and even being told by fellow Top model alumn Mame that Tyra referred to Eugena as a "bitch" during filming for Cycle 22. SO MUCH TEA! She also talks about Melrose, AJ, Jessica, CarrieDee, the twins Amanda and Michelle, Anchal, and controversial contestant Monique, She also touched on Mr. Jay Manuel and Miss Jay Alexander. Washington tells a shady story about Nigel Barker after the show, too. Finally, she talks about her historic career with Playboy. We even talk about Nicki Minaj and Azealia Banks.

The seventh cycle of America's Next Top Model started airing on September 20, 2006 as the first to be aired on The CW network.

The season's catch-phrase was "The Competition Won't Be Pretty." The season's promotional theme song was "Hot Stuff (I Want You Back)" by Pussycat Dolls.

To hustle, or not to hustle? That is the question!

After finishing in the top three on America's Next Top Model, Eugena Washington had a plan for paving her own lane in the industry, which eventually led to her becoming a Playboy Playmate of the Year. Watch the supermodel share her story and the keys to making her dream a reality.

Whether this video of Eugena Washington, intelligently reflecting on her experience of the competition, is to some extent a post rationalisation or not, the message that comes through is that success in this highly competitive media sector relies on taking a strategic approach.

This is some of her story . . .

If Representational Intersectionality highlights the importance of women of colour having representation in media and contemporary settings, then the career of of Eugena Washington is a case in point.

However, when it comes to a consideration of Spiller's notion of the pornotropic aesthetic, then things and images do not lie so easily.

For Eugena Washington the professional experience of modelling, and being photographed naked, is normalised and validated as essentially aesthetic, and therefore not predominantly sexual, or sexualised, in the ongoing production of imagery that, while being "artistic", is classifiable in the category of softcore pornography.

Originally, softcore pornography was presented mainly in the form of "men's magazines", when it was barely acceptable to show a glimpse of a woman's nipple in the 1950s. By the 1970s, in such mainstream magazines as Playboy, Penthouse and Hustler, no region of the female body was considered off limits. This accepted, normalised, but gendered convention, did not admit the depiction of erections of the penis. Softcore pornography allows the inclusion of sexual activity between two people or masturbation, but it does not contain explicit depictions of sexual penetration, cunnilingus, fellatio, or ejaculation. That's hardcore! Commercial pornography can be differentiated from erotica, which has high-art aspirations, or pretensions, according to at least two different and divergent "points of view". Somehow, by the time Playboy presents Eugena as Playmate of the Year in 2016, the classic Playboy aesthetic occupies a "liminal" zone somewhere between softcore porn and the aesthetics of erotica.

Adjacent to this "liminal" zone is a space where the pornotropic aesthetic intrudes, albeit surreptitiously, under the guise of "art".

This is a recent cover for treats, featuring the African American woman of colour Eugena Washington. Treats is an American limited-edition erotica and fine arts magazine that is primarily available by subscription. The magazine, which debuted in 2011, is described as a quarterly although it was initially only published twice a year. Adam Tschorn of the Los Angeles Times noted that his "copilot" felt that the magazine's nude photography was "virtually indistinguishable" from Playboy's despite the "fine arts quarterly" billing. Indeed, the photographer for this cover is the same Josh Ryan who photographed Eugena Washington for the Playmate of the Month feature for the December 2015 issue of Playboy.

But something is happening here that you need to understand, Mr. Jones!

Q. What is represented here?

A. The supine body of an African American woman of colour, seemingly entangled in the kind of rope normally associated with the materials supplied by a maritime chandler.

All other possible, and multiple associations are crowded out by the obvious. The contrasts embedded in this aesthetic, add up to an indexical sign system. The naked and beautiful woman, of African descent, the rope, the dark interior, all point to the "horror", the "horror" and the "horror", of the "middle passage" and the "heart of darkness".

National Museums Liverpool with its webpages on the History of Slavery, and Black Lives Matter, have a webpage describing the appalling conditions suffered by those on board enslaver ships plying their trade on The Middle Passage.

In King Leopold's Ghost (1998), Adam Hochschild wrote that literary scholars have made too much of the psychological aspects of Heart of Darkness, while paying scant attention to Conrad's accurate recounting of the "horror" arising from the methods and effects of colonialism in the Congo Free State. "Heart of Darkness is experience ... pushed a little (and only very little) beyond the actual facts of the case".

Disconcertingly, Josh Ryan's photo is lightly veiled in the guise of a tableau vivant, reminiscent of the Ziegfeld Follies, rather than a vehicle to carry the idea and/or the reality of the experience of of slavery.

The tableau vivant is itself another trope in the textual techniques and conjured imagery to be found in the writings of the Marquis De Sade.

The techniques of De Sade are considered by Roland Barthes in his book: Sade, Fourier, Loyola: (1976). He discusses the role of the tableau vivant in a section on De Sade headed:

Scene, Machine, Writing

"What a lovely group!" La Durande exclaims, seeing Juliette "occupied by four thieves from Ancona. The Sadian group is often a pictorial or sculptural object: the discourse captures the figures of debauchery not only as arranged, architectured, but above all as frozen, framed, lighted; it treats them as tableau vivants. This form of theater has been little studied, doubtless because no one does it anymore. However, must we be reminded that for a long time the tableau vivant was a bourgeois entertainment, analagous to the charade? As a child, the present author on several occasions attended, at pious and provincial charity bazaars, performances of grand tableau vivants - Sleeping Beauty, for example, he did not know that this social game is of the same fantasmatic essence as the Sadian tableau; perhaps he came to understand that later by observing that the filmic photogram is opposed to film itself because of a split which is not created by its having been extracted (one immobilizes and publishes a scene taken from a great film), but, one might say, by its having been perverted: the tableau vivant, despite the apparently total character of the figuration, is a fetish object (to immobilize, to light, to frame, means to cut up), whereas film, as function, is an hysterical activity (the cinema does not consist in animating images, the opposition between photography and film is not that of the fixed and the mobile image, cinema consists not in figuring, but in a system's being made to function)

An illustration to De Sade's Juliette

Now, despite the predominance of tableau, this split exists in Sadian text and, it appears, for the same purposes. For the "group" which is in fact a photogram of debauchery, is contrasted here and there with a moving scene. The vocabulary charged with denoting this commotion within the group (which virtually changes its nature, philosophically) is an extensive one (to execute, to continue, to vary, to break up, to disarrange). We know that this functioning scene is nothing but a machine without subject, since there is even an automatic ticking ("Minski approaches the hitched-up creature and fondles his buttocks, bites them, and all the women instantly form six ranks").

The rope! And hands tied!

What does this imagery signify?

Don't ask the meaning! Ask the use!

(Axiom borrowed from the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein)This image was used for the Guardian - The briefing (Mon 25 Feb 2019) by Kate Hodal on how slavery affects more than 40 million people worldwide – more than at any other time in history. The briefing is headlined:

One in 200 people is a slave. Why?

This image is capable of signifying . . .

. . . slavery!

Three years earlier the same Shutterstock image was used for an article in The Conversation by Kevin Bales, Professor of Contemporary Slavery, University of Hull (June 7, 2016).

Modern slave trade: how to count a ‘hidden’ population of 46 million

The Wikipedia article on the Atlantic slave trade contains an image of this painting in the article's margin on the history of the slave trade during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.

The painting's title is The Slave Trade (1840) and is by François-Auguste Biard. The aesthetic values of this work effortlessly accommodate the brutal branding of a young African woman as she is translated from the state of humanity to one of property (see detail below).

Alexander G. Weheliye's article Pornotropes (April 2008 Journal of Visual Culture 7, according to the Abstract for the article, . . .

. . . foregrounds the link between slavery and sexuality explored by Hortense Spillers . . .

. . . what Spillers calls pornotroping . . .

. . . and which exposes some of the limitations of Giorgio Agamben's `homo sacer' (sacred man) figure by calling attention to how political violence frequently produces forces that exceed it.

Giorgio Agamben is a philosopher best known for his work investigating the concepts of the state of exception, form-of-life (borrowed from Ludwig Wittgenstein) and homo sacer. The concept of biopolitics (carried forth from the work of Michel Foucault) informs many of his writings. More recently Agamben, has courted controversy in an article published by Il Manifesto on 26 February 2020, promoting the misinformation that the COVID-19 pandemic was an "invention":

"In order to make sense of the frantic, irrational, and absolutely unwarranted emergency measures adopted for a supposed epidemic of coronavirus, we must begin from the declaration of the Italian National Research Council (NRC), according to which 'there is no SARS-CoV2 epidemic in Italy.' and 'the infection, according to the epidemiological data available as of today and based on tens of thousands of cases, causes light/moderate symptoms (a variant of flu) in 80-90% of cases. In 10-15%, there is a chance of pneumonia, but which also has a benign outcome in the large majority of cases. We estimate that only 4% of patients require intensive therapy.'"A case of intellectual arrogance, and ignorance, in the face of reality?

On this Re:LODE Radio passes and returns to the matters raised in Alexander G. Weheliye's article Pornotropes, where there's an analysis of the film Sankofa.

Sankofa is a 1993 Ethiopian-produced drama film directed by Haile Gerima centred on the Atlantic slave trade. The word Sankofa derives its meaning from the Ghanaian Akan language which means to "go back, look for, and gain wisdom, power and hope," and stresses the importance of not drifting too far from one's past in order to progress in the future. Gerima uses the journey of the character Mona, a photographer's model, to show how the African perception of identity included recognising where you come from and "returning to one’s source" (Gerima).

The film opens with the scene of an elderly Divine Drummer, Sankofa, beating on African drums and chanting the phrase "Lingering spirit of the dead, rise up." This is a direct communication with the ancestors of the African lands, specifically Ghana, and bringing the spirit of his ancestors who were killed in the African diaspora back home.

The story then goes on to show Mona, a contemporary African-American model on a film shoot in Ghana. She has a session at Cape Coast Castle, which she does not know was historically used for the Atlantic slave trade. While Mona is on the beach modeling, she encounters the mysterious old man Sankofa. Sankofa tells Mona to return to her past. When Mona decides to go take a look inside the castle herself, she gets trapped inside and enters a sort of trance in which she is surrounded by chained slaves who appear to have risen from the dead.

Mona attempts to run out of the slave castle and is met by white slave masters who she tries to reason with and claiming that she is of American descent and not of African descent. The slave masters pay no attention to Mona's claim and push her to a fire, strip off her clothing, and put a hot iron on her back.

Mona is then transported into the body of a house servant named Shola "to live the life of her enslaved ancestors." She is taken to the Lafayette plantation in the Southern United States where she suffers abuse by her slave masters and becomes a victim of rape.

Ostensibly an uplifting narrative about the horrors of slavery, Alexander G. Weheliye's article considers the risk that the cinematic depiction of the historical reality of slavery cannot help but eroticise the brutality that the filmmaker seeks to denounce, and which demonstrates the visual logic of pornotroping. Is this a problem that originates in film and is embedded in cinema, and therefore a quality immanent in the medium itself?

Medium HOT? Medium COOL?

So, back to the Playboy Interview with Marshall McLuhan to help answer these questions!

In this interview McLuhan explains this essential difference between a high definition media technology and a low definition medium. In Understanding Media McLuhan has a chapter titled Media Hot and Cold where he says:

A hot medium is one that extends one single sense in "high definition." High definition is the state of being well filled with data. A photograph is, visually, "high definition."Speech is a cool medium of low definition, because so little is given and so much has to be filled in by the listener.

On the other hand, hot media do not leave so much to be filled in or completed by the audience.

Hot media are, therefore, low in participation, and cool media are high in participation or completion by the audience.

Naturally, therefore, a hot medium like radio has very different effects on the user from a cool medium.Any hot medium allows of less participation than a cool one, as a lecture makes for less participation than a seminar, and a book for less than dialogue.

Some Like It HOT!

Film, or the "Movies", or "Cinema", or High Definition Video formats are therefore HOT!

McLuhan's take on the movies, or the Reel World, in Understanding Media includes these pointers as a way to understand how the medium of film is itself the message. He says:

Movies as a nonverbal form of experience are like photography, a form of statement without syntax. In fact, however, like the print and the photo, movies assume a high level of literacy in their users and prove baffling to the nonliterate.

It was Rene Clair who pointed out that if two or three people were together on a stage, the dramatist must ceaselessly motivate or explain their being there at all. But the film audience, like the book reader, accepts mere sequence as rational. Whatever the camera turns to, the audience accepts. We are transported to another world. As Rene Clair observed, the screen opens its white door into a harem of beautiful visions and adolescent dreams, compared to which the loveliest real body seems defective.

The close relation, then, between the reel world of film and the private fantasy experience of the printed word is indispensable to our Western acceptance of the film form. Even the film industry regards all of its greatest achievements as derived from novels, nor is this unreasonable. Film, both in its reel form and in its scenario or script form, is completely involved with book culture.

. . . the screen opens its white door into a harem of beautiful visions and adolescent dreams, compared to which the loveliest real body seems defective.

Film, both in its reel form and in its scenario or script form, is completely involved with book culture. All one need do is to imagine for a moment a film based on newspaper form in order to see how close film is to the book. Theoretically, there is no reason why the camera should not be used to photograph complex groups of items and events in dateline configurations, just as they are presented on the page of a newspaper.

The realistic novel, that arose with the newspaper form of communal cross-section and human-interest coverage in the eighteenth century, was a complete anticipation of film form.

Hot stuff? The book, the genre, the film and how realism conforms to the pornotropic?

Re:LODE Radio attempts to consider how these "understandings" point to the pornotropic aesthetic as it applies to 12 Years a Slave, the 2013 biographical period-drama film directed by Steve McQueen, an adaptation of the 1853 slave memoir Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northup. The writer for this film was John Ridley but the starting point for the film project began when the director's partner, Bianca Stigter, came across Northup's 1853 memoir, a "realistic account" of a New York State-born free African-American man who was kidnapped in Washington, D.C., by two conmen in 1841 and sold into slavery. Northup was put to work on plantations in the state of Louisiana for 12 years before being released. The first scholarly edition of Northup's memoir, co-edited in 1968 by Sue Eakin and Joseph Logsdon, carefully retraced and validated the account and concluded it to be accurate. Other characters in the film were also real people, including Edwin and Mary Epps, and Patsey.

McQueen later told an interviewer:"I read this book, and I was totally stunned. At the same time, I was pretty upset with myself that I didn't know this book. I live in Amsterdam where Anne Frank is a national hero, and for me, this book read like Anne Frank's diary but written 97 years before – a firsthand account of slavery. I basically made it my passion to make this book into a film."

Historian James Olney has observed that "slave autobiographies, when read one next to another, display an 'overwhelming sameness.'" That is, though the autobiography by definition suggests a unique and personal story, that slave narratives present a genre of autobiographies that tell essentially the same story. When read in conjunction, as in this anthology, there is a distinct repetitiveness. While this repetitiveness disallows the creativity and shaping of one's personal story, as Olney argues, it was equally important for slave narratives to follow a form that corroborated with the stories of others to create a collective picture of slavery as it then existed. In fact, the "same" form presented in all of these unique and individual stories created a powerful and resounding message of the consistent evils of slavery and the necessity of its demise."

A journal article published by The Johns Hopkins University Press and written by Sam Worley states that "Northup’s narrative, though well known, has often been treated as a narrative of the second rank, albeit one with an unusually exciting and involving story as well as, thanks to the research of its modern editors, Sue Eakin and Joseph Logsdon, one with considerable historical value."

Noah Berlatsky's article on the film in The Atlantic (28 October 2013) is headlined: How 12 Years a Slave Gets History Right: By Getting It Wrong, and then in a subheading opines:

Steve McQueen's film fudges several details of Solomon Northup's autobiography — both intentionally and not — to more completely portray the horrors of slavery.

Berlatsky quotes critic Isaac Butler who had recently written a post attacking:

"what he called the "realism canard" — the practice of judging fiction by how well it conforms to reality. "We're talking about the reduction of truth to accuracy," Butler argues, and adds, "What matters ultimately in a work of narrative is if the world and characters created feels true and complete enough for the work's purposes." (Emphasis is Butler's.)

Berlatsky thinks:His point is well-taken. But it's worth adding that whether something "feels true" is often closely related to whether the work manages to create an illusion not just of truth, but also of accuracy. Whether it's period detail in a costume romance or the brutal cruelty of the drug trade in Breaking Bad, fiction makes insistent claims not just to general overarching truth, but to specific, accurate detail. The critics Butler discusses may sometimes reduce the first to the second, but they do so in part because works of fiction themselves often rely on a claim to accuracy in order to make themselves appear true.

This is nowhere more the case than in slave narratives themselves. Often published by abolitionist presses or in explicit support of the abolitionist cause, slave narratives represented themselves as accurate, first-person accounts of life under slavery. Yet, as University of North Carolina professor William Andrews has discussed in To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, the representation of accuracy, and, for that matter, of first-person account, required a good deal of artifice. To single out just the most obvious point, Andrews notes that many slave narratives were told to editors, who wrote down the oral account and prepared them for publication. Andrews concludes that "It would be naïve to accord dictated oral narratives the same discursive status as autobiographies composed and written by the subjects of the stories themselves."

12 Years a Slave is just such an oral account. Though Northup was literate, his autobiography was written by David Wilson, a white lawyer and state legislator from Glens Falls, New York. While the incidents in Northup's life have been corroborated by legal documents and much research, Andrews points out that the impact of the autobiography — its sense of truth—is actually based in no small part on the fact that it is not told by Northup, but by Wilson, who had already written two books of local history. Because he was experienced, Andrews says, Wilson's "fictionalizing … does not call attention to itself so much" as other slave narratives, which tend to be steeped in a sentimental tradition "that often discomfits and annoys 20th-century critics." Northup's autobiography feels less like fiction, in other words, because its writer is so experienced with fiction. Similarly, McQueen's film feels true because it is so good at manipulating our sense of accuracy. The first sex scene, for example, speaks to our post-Freud, post-sexual-revolution belief that, isolated for 12 years far from home, Northup would be bound to have some sort of sexual encounters, even if (especially if?) he does not discuss them in his autobiography.

The difference between book and movie, then, isn't that one is true and the other false, but rather that the tropes and tactics they use to create a feeling of truth are different. The autobiography, for instance, actually includes many legal documents as appendices. It also features lengthy descriptions of the methods of cotton farming. No doubt this dispassionate, minute accounting of detail was meant to show Northup's knowledge of the regions where he stayed, and so validate the truth of his account. To modern readers, though, the touristy attention to local customs can make Northup sound more like a traveling reporter than like a man who is himself in bondage. Some anthropological asides are even more jarring; in one case, Northup refers to a slave rebel named Lew Cheney as "a shrewd, cunning negro, more intelligent than the generality of his race." That description would sound condescending and prejudiced if a white man wrote it. Which, of course, a white man named David Wilson did.

A story about slavery, a real, horrible crime, inevitably involves an appeal to reality — the story has to seem accurate if it is to be accepted as true. But that seeming accuracy requires artifice and fiction — a cool distance in one case, an acknowledgement of sexuality in another. And then, even with the best will in the world, there are bound to be mistakes and discrepancies, as with Mistress Epps's plea for murder transforming into Patsey's wish for death. Given the difficulties and contradictions, one might conclude that it would be better to openly acknowledge fiction. From this perspective, Django Unchained, which deliberately treats slavery as genre, or Octavia Butler's Kindred, which acknowledges the role of the present in shaping the past through a fantasy time-travel narrative, are, more true than 12 Years a Slave or Glory precisely because they do not make a claim to historical accuracy. We can't "actually witness … American slavery" on film or in a book. You can only experience it by experiencing it. Pretending otherwise is presumptuous.

But refusing to try to recapture the experience and instead deciding to, say, treat slavery as a genre Western, can be presumptuous in its own way as well. The writers of the original slave narratives knew that to end injustice, you must first acknowledge that injustice exists. Accurate stories about slavery — or, more precisely, stories that carried the conviction of accuracy, were vital to the abolitionist cause.

Sentimentality? Pornography? Pornotropia?

The content and subject matter of the film is shaped by a determination to realise the experience and witness in Northup's "realistic account".

There are two "scenes" in McQueen's film that Re:LODE Radio considers particularly in terms of form and content. Firstly, a scene of an attempted lynching, that follows on from a growing tension between Northup and plantation carpenter John Tibeats finally breaks as Tibeats tries to beat Northup. Northup snaps and beats Tibeats with his hands before beating him with his own whip. Tibeats and his group try to lynch Northup, but they are stopped by the plantation overseer.

The long take that McQueen chooses to subject his audience, where Northup is left on tiptoes with the noose around his neck for hours before Ford arrives and cuts Northup down is excruciating to witness. This effect is amplified in this extended scene by its being rendered visually as an example and apogee of what some would consider an "aesthetic purity". This includes the continuation of a production value in cinematography, consistent throughout the film, at its most intense, in high definition, in sunlight, shadow and near silence.

This type of visual aesthetic is the opposite of the kind McQueen used in his 2002 Caribs Leap.

The second scene is of a sustained and brutal whipping of Patsey, a favoured slave who can pick over 500 pounds of cotton a day, twice the usual quota. The plantation and slave owner Epps regularly rapes Patsey while his wife abuses and humiliates her out of jealousy. Patsey is caught by Epps going to a neighbouring plantation in order to acquire soap, as Mrs. Epps will not let her have any. In retaliation, Epps orders Northup to whip Patsey. Rather than risk harm to himself, Northup accepts the whip from Epps and strikes Patsey over a dozen times, drawing blood, tears, and shrieks. Epps then takes the whip back from Northup, and whips Patsey brutally, to the point of near death.

Steve McQueen is quoted as saying:

"There's a subtlety that leads up to the crescendo of Patsy being whipped by Solomon. I had to do it because I couldn't look at myself in the mirror as an artist and not do it that way."But, what kind of artist, and what kind of mirror?

The end result of the process of realising in a heightened and high definition "pure" and "visual aesthetic", a reality that originates in experience, then translated into the text of a "realistic account", ends up with the cinematic depiction of the historical reality of slavery risking the eroticising of the brutality that the filmmaker seeks to denounce.

This video montage begins with an edit by Double FacePalm, Gone With The Wind vs 12 Years a Slave. They explain:

Two movies separated by decades of film-making and sociological changes but set in the same era in the same location. Their themes were bound to overlap but I didn't think they would contradict so dramatically. It's interesting to see the theme of racial oppression skimmed over in GWTW, made in a time where segregation was still widely practised vs a modern film made when oppression is openly ridiculed.

If only!

Gone With The Wind . . .

Their edit ends with the 12 Years a Slave scene of the brutal whipping of Patsy. The audience knows that this scene, the "crescendo", according to McQueen, is a construction. Adam B. Vary, BuzzFeed News Reporter, looks at this scene in his report:

Inside The Most Unforgettable Scene In "12 Years A Slave"

In this piece the actors Chiwetel Ejiofor and Lupita Nyong'o, and screenwriter John Ridley, explain how they weathered bringing a scene of unspeakable brutality to life on screen.

At the Toronto Film Festival, screenwriter John Ridley (Red Tails) told me that the most difficult thing about the scene for him as a writer was not allowing Solomon to prevent Patsey from coming to any real harm. "You wanted Solomon to do more, but you realize the circumstances, he couldn't," he said. "You don't want that to go down the way it went down." Ridley added that once he committed to capturing the scene as Northup described in his memoir, the intellectual exercise of giving the scene its necessary cinematic structure allowed him to remain at a remove. But after seeing the sequence once in a private screening room, he says he could not bring himself to watch it again at the film's gala premiere at Toronto.

"I can't imagine what it was like being an actor in that moment and having to channel those things," he said. "That's a moment where I was very glad to just be the writer."

So how did the actors get through being in the scene?

Logistically, it was a matter of some old-school camera trickery — the whip never came close to Nyong'o's back, but it looked like it did thanks to the camera angles director Steve McQueen chose for the scene, and Nyong'o moving her body as if she was being whipped. And when the camera swings around to capture the ruin inflicted upon Patsey's back, the effect is a combination of practical make-up and CGI.

Emotionally, however, it was far less cut-and-dried. For Nyong'o — acting in her very first feature film — it was about finding the right psychological touchstone to help her arrive at a place where she could do her job.

"Patsey in the book, in the script, is described as being effortlessly sensual," she told me. "I thought about that for a long time. What does that mean, to be effortlessly sensual? Then I found this quote from James Baldwin's book A Fire Next Time. He says, 'To be sensual, I think, is to [respect and] rejoice in the force of life, of life itself, and to be present in everything that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread.' That was Patsey. She was present. So that was a guiding principle for that scene. I couldn't possibly prepare for it an any other way than just to be there."

And being there was more than enough to handle. "The reality of the day was that I was stripped naked in front of lots of people," Nyong'o said. "It was impossible to make that a closed set. In fact, I didn't even ask for it to be a closed set, because at the end of the day, that was a privilege not granted to Patsey, you know? It really just took me there. It was devastating to experiencing that, and to be tied to a post and whipped. Of course, I couldn't possibly be really whipped. But just hearing the crack of that thing behind me, and having to react with my body, and with each whip, get weaker and weaker…" She grew quiet, and sighed. "I mean, it was — I didn't practice it. It was just — it was an exercise of imagination and surrender."

At a remove?

For the writer John Ridley what was bearable as text, in the original account, and in his screenplay, when the "realistic account" was translated to a new level as a visual form, and in high definition, and experienced in the "reel world" of a photographic hyperreality - cinema, it became intolerable.

Marshall McLuhan in his chapter on the HOT and the COOL includes this example of a documented effect of a hot media event upon a captive audience:

An Associated Press story from Santa Monica, California, August 9, 1962, reported how:

Nearly 100 traffic violators watched a police traffic accident film today to atone for their violations. Two had to be treated tor nausea and shock.

Viewers were offered a $5.00 reduction in fines if they agreed to see the movie, Signal 30, made by Ohio State police.

It showed twisted wreckage and mangled bodies and recorded the screams of accident victims.

Whether the hot film medium using hot content would cool off the hot drivers is a moot point. But it does concern any understanding of media.

The effect of hot media treatment cannot include much empathy or participation at any time.

Cooling it!

In the context of the 1960's Cold War, and a policy of nuclear deterrence (or mutually assured destruction - M.A.D.), McLuhan goes on to say:

Is it not evident in every human situation that is pushed to a point of saturation that some precipitation occurs? When all the available resources and energies have been played up in an organism or in any structure there is some kind of reversal of pattern.

The spectacle of brutality used as deterrent can brutalise.

Brutality used in sports may humanize under some conditions, at least. But with regard to the bomb and retaliation as deterrent, it is obvious that numbness is the result of any prolonged terror, a fact that was discovered when the fallout shelter program was broached. The price of eternal vigilance is indifference.

Q. What alternative strategy does McLuhan propose?

A. The cultural strategy that is desperately needed is humour and play. It is play that cools off the hot situations of actual life by miming them.

The passive consumer wants packages, but those . . . who are concerned in pursuing knowledge and in seeking causes will resort to aphorisms, just because they are incomplete and require participation in depth.

The principle that during the stages of their development all things appear under forms opposite to those that they finally present is an ancient doctrine.

Interest in the power of things to reverse themselves by evolution is evident in a great diversity of observations, sage and jocular.

Alexander Pope wrote:

Vice is a monster of such frightful mien As to be hated needs but to be seen; But seen too oft, familiar with its face, We first endure, then pity, then embrace.

Having endured, then pitied, the embrace is actually NO SUCH THING! It's a visual spectacle where audience derives a certain uncomfortable - to - comfortable pleasure in a constructed and ideological distance. And that ends up being an entirely fake version of power relations for consumption on the internet.

Sentimentality, like pornography, is fragmented emotion: a natural consequence of a high visual gradient in any culture!

Feelings of horror generated by the whipping of Patsey by Epps in 12 Years a Slave reveals a crucial and unintended discrepancy in the dramatic or empathetic effect. Re:LODE Radio wonders:

Is this film an artwork or a horror movie?

If this directorial ploy had been an intended or deliberate discrepancy the art and the work would mark a signifiant shift in character and quality. The potential for such a subversive approach, the creative use of a catachresis has probably been missed, though it was probably never looked for in the first place. The production line from "realistic account" through screenplay and treatment to shooting and editing is a continuous and un-interruptible industrial process. Classic! No wonder then that the accolade at the Oscars for McQueen and the film, undoubtedly reflects the values of the Academy and as an example of the white saviour narrative in film. Tierney Sneed said in U.S. News & World Report the year after the film was released, "Doubts still lingered about its ability to truly bring about a newfound racial consciousness among a national, mainstream audience ... The film also was a period piece that featured a happy ending ushered in by a 'white savior' in the form of Brad Pitt's character." At The Guardian, black Canadian author Orville Lloyd Douglas said he would not be seeing 12 Years a Slave, explaining: "I'm convinced these black race films are created for a white, liberal film audience to engender white guilt and make them feel bad about themselves. Regardless of your race, these films are unlikely to teach you anything you don't already know." A Black writer Michael Arceneaux wrote a rebuttal essay "We Don't Need To Get Over Slavery... Or Movies About Slavery". Arceneaux criticized Douglas for being ignorant and having an apathetic attitude towards black Americans and slavery.

In Jacques Derrida's ideas of deconstruction, catachresis refers to the original incompleteness that is a part of all systems of meaning. He proposes that metaphor and catachresis are tropes that ground philosophical discourse.

Postcolonial theorist Gayatri Spivak applies this word to "master words" that claim to represent a group, e.g., women or the proletariat, when there are no "true" examples of "woman" or "proletarian". In a similar way, words that are imposed upon people and are deemed improper thus denote a catachresis, a word with an arbitrary connection to its meaning.

In Calvin Warren's Ontological Terror: Blackness, Nihilism, and Emancipation, catachresis refers to the ways Warren conceptualises the figure of the black body as vessel or vehicle in which fantasy can be projected. Drawing primarily from the "Look a Negro" moment in Frantz Fanon's Black Skin, White Masks, Chapter 5: "The Fact of Blackness", Warren works from the notion that "the black body…provides form for a nothing that metaphysics works tirelessly to obliterate", in which "the black body as a vase provides form for the formlessness of nothingness. Catachresis creates a fantastical place for representation to situate the unrepresentable (i.e. blackness as nothingness)."

When it comes to a deliberate discrepancy what about De Sade? When dialogue begins, propaganda ends!

De Sade's strategies and tactics in the text Philosophy in the Bedroom is to intersperse a number of philosophical dialogues with a number of pornographic episodes.

This is "clickbait" before "clickbait", and where the attempt to expose the fallacies of normative social values, using textual images of phalluses and orifices, depends on the Baudelairean "Hypocrite lecteur", or "Hypocrite reader", addressed as "You!" (surely, and therefore, pointing to "us"), juggling the erotic and philosophical in an "Enlightenment sleepover".

"The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom""Enough or too much"

Just two of The Proverbs of Hell, by William Blake to be found in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

Police Open Probe Against Obscene Play

Police in Hamburg are investigating a Spanish theater group for displays of pornographic sex and bestiality in a controversial play which premiered in the city last week.This controversy was reported by DW 24.08.2004:The play "XXX" by Catalan theater group La Fura dels Baus is based on a 1795 story, "Philosophy of the Bedroom" by French playwright the Marquis de Sade. Notorious for its uninhibited display of naked lust and violence, the multimedia performance is billed as a modern theatrical response to the porn industry.

But its scenes depicting graphic incest, rape and pornography proved too much to bear to theater-goers in Hamburg last week.Violence and bestialityFollowing reports in Germany' mass-selling tabloid Bild on Friday that the play included a video sequence showing a woman having sex with a donkey, Hamburg police opened a probe against the Spanish group for the "spread of violence and bestiality."

A police officer called in to investigate said, "Bestiality is a crime punishable by up to five years in prison."

A separate report said an outraged woman in the audience alerted police after witnessing scenes of urination and simulated rape and oral sex during the play's opening night. The play is also said to have encouraged two audience members to come on stage and masturbate to make it more interactive.A separate report said an outraged woman in the audience alerted police after witnessing scenes of urination and simulated rape and oral sex during the play's opening night. The play is also said to have encouraged two audience members to come on stage and masturbate to make it more interactive.

Many theater-goers who went to see the 105-minute performance at Hamburg's Kampnagel Theater are said to have walked out in disgust halfway through. Others asked for a ticket refund.Freedom of expression?"First we'll probe whether the video is covered by the right to freedom of expression," a spokeswoman for Hamburg's state prosecutor said. She added that no charges had been filed relating to the play. "We're investigating in general against all responsible for the performance," she added.

It's not the first time that the Spanish group has run into trouble for the controversial play. Two years ago it created a furor when it opened in Frankfurt. Last year the Spanish production met with protests and police investigations in London.

Meanwhile the Kampnagel Theater in Hamburg, famous for its experimental performances, has announced it has dropped the offensive video from the performance."Apart from that, the play will continue unchanged," a spokesman for the theater told news agency DPA. "We reckon that the investigation will be dropped because 'XXX' is an entire artwork," he added.

Hamburg's Cultural Ministry has thrown its weight behind the theater. "It's an important and correct play, it plays with the boundaries between pornography and art," spokesman Björn Marzahn told DPA.

The ministry, he said, welcomed the fact that the Kampnagel Theater had reacted so promptly to the criticism and excised out the controversial video from the play.

'We use the body as theatre'

The Guardian reported on Fura dels Baus in 2007. Laura Barnett (Thu 19 Jul 2007) writes:

La Fura dels Baus certainly know how to make an entrance. The last time the Barcelona theatre collective came to Britain, they brought a hardcore theatrical sex show called XXX. It sparked a tabloid storm and an investigation by Scotland Yard into whether "criminal activities", aka sex acts, were committed on stage (they were not).

Nudity is pretty much La Fura's calling card: in XXX, a rendering of the writings of the Marquis de Sade featuring re-enactments of sex, torture and mutilation, the actors were rarely clothed. Its run in London and the Edinburgh Festival in 2003 prompted irate tabloid headlines - "Stop this filth," stormed one - along with predominantly scathing reviews and the involvement of the vice squad.

What about crowd participation? Audience plants at XXX rushed the stage to indulge in "sex acts", and spectators at La Fura's 1997 production Manes in London's Docklands were pelted with plastic chickens and drenched with buckets of water.

Sex Acts?

An XXX review - Edinburgh Fringe Festival - says:

From the very start XXX hands out both a full responsibility and an invitation to participate. As the audience enters one finds out that by sending a text message via mobile phone to a given number, his or her message appears projected on the stage. La Fura cleverly, and to set the mood, turn a passive moment into something that involves the audience. The show is a free adaptation of the Marquis De Sade's Philosophy of the Boudoir, and as such it is not surprising that it involves a lot of sex, and a lot of 'uncommon' practices.Philosophy in the Bedroom

The plot is rather simple: we observe as the young and innocent Eugenia is taught a number of lessons in depravity by a group of three libertines, Lula, a glamorous Madame/porn star, her incestuous brother Giovanni, and the aggressive Dolmance. The lessons go from how to pleasure a woman orally, to sadism and ultimately raping her own mother.

However the real shock of the piece is the way it portrays sex as an experience that has become extremely mediated.

This is slightly drilled into the audience as we are confronted with pornography clips, cyber-sex, a menu of sex toys and sex machines, and ultimately a live cam-chat with a girl somewhere in a strip club in Barcelona.De Sade's text is equally revolutionary and in addition to it we hear statements such as 'Plastic is much better than flesh' or 'Time and body no longer exist'. Formally the performance is equally mediated as a camera is moved around stage filming the actors. Theatre becomes cinema as camera angles impossible to archive due to the proscenium arch are projected on stage. We constantly see screens upon screens, or behind screens. The effect of seeing the actors' actions superimposed, on stage and on screen is somewhat dazzling at first, but ultimately works in favour of what La Fura is trying to say, or rather, shouting out at us. There is of course a great sense of humour in the piece, as it does not portray sex as something necessarily obscure and dirty but as having delicate and complex balance. The two best examples of this 'toilet humour' are a conversation one of the four characters has with his disappointed penis, projected on stage but appearing with a talking mouth; and the presentation of the 'Globalised Cunt' that comes with it's own travel case and it's own incorporated light. This light-hearted mood is broken on several occasions shortly after it settles on stage, making XXX a true rollercoaster. Moreover the show does not stop at the proscenium arch, it rolls into the auditorium to see if any adventurous audience members want a ride. There is a 'pheromone experiment' in which the audience are sprayed with pheromones and the lights turned off, whilst a crew members passes row after row recording with night-vision what people do. When the lights come back on, one of the characters is so disappointed in the audience's inability to spontaneously start an orgy that he starts asking for volunteers. Without giving too much away all I will say is that several spectators do get naked during the performance, one even receiving a fellatio from one of the characters. But don't be unnecessarily alarmed, not all you see in XXX is absolutely real. No, there is no live sex on stage and no, there probably were no pheromones. There are more important things to think and debate with yourself about, than whether it is all real or not. It is a piece with a sharp philosophical and political message, and it does not bite its tongue. The rhythm is frenetic and the images stunning. As you may guess, this is not a show for kids, the prude or fainthearted, but will certainly entertain anyone willing to take up a challenge. Whether you decide to remain in your seat or not, XXX makes you question your moral standards and preconceptions as well as question what kind of a society produces this kind of mediated 'sex'.

Why is there a continued fascination with De Sade?

There continues to be a fascination with de Sade among scholars and in popular culture. Prolific French intellectuals such as Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault published studies of him.

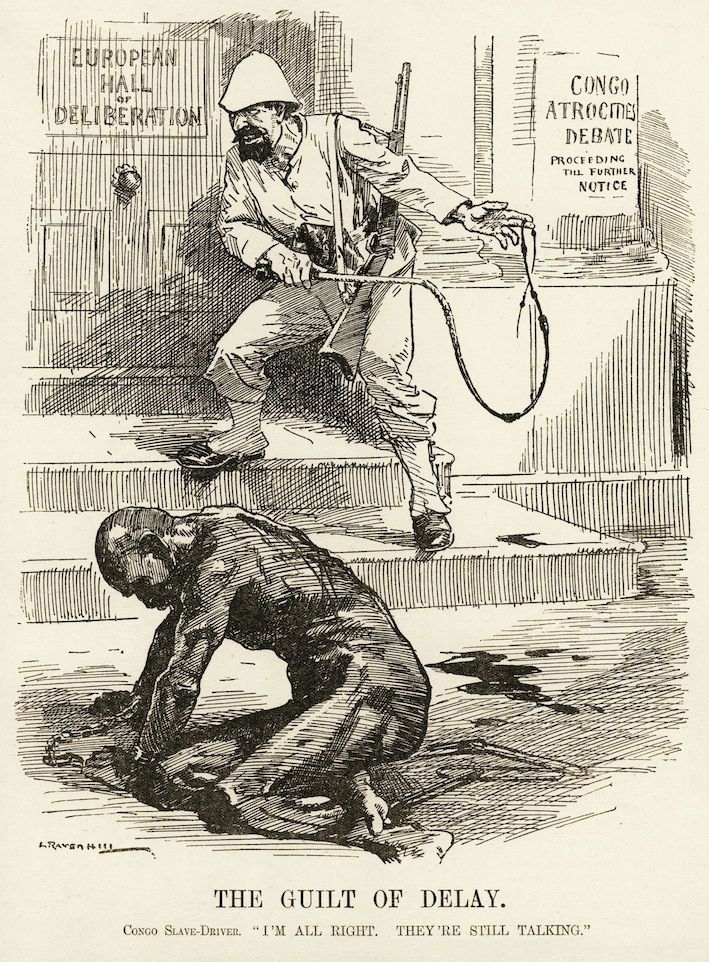

Re:LODE Radio hazards the suggestion that this continuing interest in de Sade relates to the abiding fascination in "horror" as a genre within popular culture, and reflects the violence and "the heart of darkness" at the core of a capitalist European class society, that profits from imperialism, colonialism, racism, but revealed when the veil that covers the truth is torn away, by Sade, amongst many other artists and philosophers.Geoffrey Gorer, an English anthropologist, and noted for his application of psychoanalytic techniques to anthropology, wrote one of the earliest books on Sade, entitled The Revolutionary Ideas of the Marquis de Sade in 1935. He pointed out that Sade was in complete opposition to contemporary philosophers for both his "complete and continual denial of the right to property" and for viewing the struggle in late 18th century French society as being not between "the Crown, the bourgeoisie, the aristocracy or the clergy, or sectional interests of any of these against one another", but rather all of these "more or less united against the proletariat." By holding these views, he cut himself off entirely from the revolutionary thinkers of his time to join those of the mid-nineteenth century. Thus, Gorer argued, "he can with some justice be called the first reasoned socialist."Simone de Beauvoir in her essay Must we burn Sade?, published in Les Temps modernes, December 1951 and January 1952, and other writers have attempted to locate traces of a radical philosophy of freedom in Sade's writings, preceding modern existentialism by some 150 years.

He has also been seen as a precursor of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis in his focus on sexuality as a motive force.

The surrealists admired him as one of their forerunners, and Guillaume Apollinaire famously called him "the freest spirit that has yet existed".Pierre Klossowski, in his 1947 book Sade Mon Prochain ("Sade My Neighbour"), analyzes Sade's philosophy as a precursor of nihilism, negating Christian values and the materialism of the Enlightenment.One of the essays in Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno's Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947) is titled "Juliette, or Enlightenment and Morality" and interprets the ruthless and calculating behaviour of Juliette as the embodiment of the philosophy of Enlightenment. By associating the Enlightenment and Totalitarianism with Marquis de Sade's works—especially Juliette, in excursus II — the text also contributes to the pathologisation of sadomasochist desires, as discussed by sexuality historian Alison Moore (Moore, Alison M. 2015. Sexual Myths of Modernity: Sadism, Masochism and Historical Teleology. Lanham: Lexington Books). In the Introduction to this work the author writes:Tracking the usage of the words ‘sadism’ and ‘masochism’ from their invention by European psychiatry in the nineteenth century, to their theorization in twentieth-century psychoanalysis of culture, and to their articulation in descriptions of Nazism, this book aims to show that the nexus linking perversion to barbarism within an historical teleology of progress has a continuous genealogy which has not yet passed from use, and is never acknowledged by any of those who repeat these patterns of thought.

In this sense itcan be understood as the true ‘unconscious’ that continues to haunt understandings of violence and progress, though this book does not attempt a transcendental analytic reading of culture in the style of Horkheimer, Lacanor Žižek; Instead it follows a genealogical approach focused on both the direct and contextual relations between later ideas and their earlier incarnations. I have chosen the word ‘myths’ to describe these patterns of thought and representations about sexuality, violence, progress and modernity, cognisant of the specific uses of this term in various disciplines. It is the multiple meanings of the term that make it perhaps the only fitting word for the elaborate multiplicity of ideas that linked sexual perversions to the corruption of modernity. But if the reader is reminded of a certain sociological definition of myth as a kind of binding story of past origins that secures social identity, this will not be inappropriate to the ideas described in this book; nor will the reader be misled if reminded of Roland Barthes’s notion of ‘mythologies’, which drew attention to the way myths in modernity become naturalised, and thereby form the contents of unthinking repetitions.

Similarly, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan posited in his 1963 essay Kant avec Sade that Sade's ethics was the complementary completion of the categorical imperative originally formulated by Immanuel Kant.In contrast, G. T. Roche argued in An Unblinking Gaze: On the Philosophy of the Marquis de Sade that Sade, contrary to what some have claimed, did indeed express a specific philosophical worldview. He criticizes Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer's view in their work Dialectic of Enlightenment. Additionally, he criticizes the idea Sade demonstrated morality cannot be based on reason.In his 1993 Political Theory and Modernity, William E. Connolly analyzes Sade's Philosophy in the Bedroom as an argument against earlier political philosophers, notably Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Thomas Hobbes, and their attempts to reconcile nature, reason, and virtue as bases of ordered society.

Similarly, Camille Paglia argued that Sade can be best understood as a satirist, responding "point by point" to Rousseau's claims that society inhibits and corrupts mankind's innate goodness: Paglia notes that Sade wrote in the aftermath of the French Revolution, when Rousseauist Jacobins instituted the bloody Reign of Terror and Rousseau's predictions were brutally disproved. "Simply follow nature, Rousseau declares. Sade, laughing grimly, agrees."In The Sadeian Woman: And the Ideology of Pornography (1979), Angela Carter provides a feminist reading of Sade, seeing him as a "moral pornographer" who creates spaces for women.

Similarly, Susan Sontag defended both Sade and Georges Bataille's Histoire de l'œil (Story of the Eye) in her essay "The Pornographic Imagination" (1967) on the basis their works were transgressive texts, and argued that neither should be censored.

By contrast, Andrea Dworkin saw Sade as the exemplary woman-hating pornographer, supporting her theory that pornography inevitably leads to violence against women. One chapter of her book Pornography: Men Possessing Women (1979) is devoted to an analysis of Sade. Susie Bright claims that Dworkin's first novel Ice and Fire, which is rife with violence and abuse, can be seen as a modern retelling of Sade's Juliette.

On the other hand the French hedonist philosopher Michel Onfray has attacked this tendency to reclaim Sade as innovative, transgressive and political, in his writing, and declaring that "It is intellectually bizarre to make Sade a hero."

Edgar Degas' 'Scène de guerre au Moyen-âge', 1865, is one of the exhibits said to be inspired by Sade (RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay)

On the occasion of an art exhibition in Paris to celebrate Sade's 200th anniversary in 2014, The Independent newspaper referenced Onfray's position. John Lichfield writes (Friday 14 November 2014):

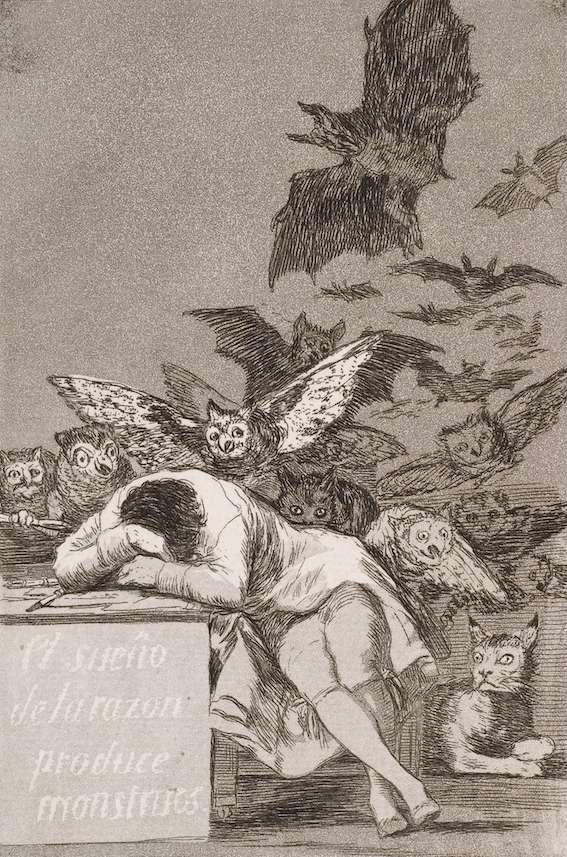

In his many guises, including nearly 30 years as a prisoner under three regimes, royal, republican and imperial, the marquis never turned his hand to painting. It seems perverse, therefore, for the Musée d’Orsay in Paris to celebrate his 200th anniversary with an art exhibition.“Sade – Attaquer le soleil” (Sade – attacking the sun) seeks to prove that Sade’s writing, although officially banned in France until the 1950s, had an enormous impact on 19th- and 20th-century art. It traces – sometimes convincingly, sometimes wilfully – Sade’s influence on the work of, amongst others, Ferdinand-Victor-Eugène Delacroix, Francisco Goya, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso and the surrealists.The exhibition is part of a bicentenary push by French intellectuals to release Sade, who lived from 1740 to 1814, from the shadows and into the literary and artistic mainstream. There is an avalanche of new books. There is an exhibition in Paris of his letters and manuscripts, including the scroll of The 120 Days of Sodom whose catalogue of 600 recommended “passions” includes the rape of children as young as five. The “divine”, or damned, marquis also made his bow this week as a character in a video game in the Assassin’s Creed series.Since he was “rediscovered” and championed by the poet Guillaume Apollinaire in 1909, Sade has been placed by some of his admirers alongside Rousseau or Voltaire as one of the French 18th-century iconoclasts who “killed God”, smashed the mould of conventional thought and created the modern world.Pierre Guyotat, a French erotic-literary novelist, says: “Sade is, in a way, our Shakespeare. He has the same sense of tragedy, the same sweeping grandeur. Taking pleasure in the suffering of others is not such an important part of his writings as people claim. He has his tongue sticking out permanently. He is incessantly ironic.”To claim Sade as humanist and liberator, rather than deviant or pervert, sticks in the throat of other intellectuals. A new book by the philosopher Michel Onfray (La Passion de la Méchanceté or the “passion for wickedness”) makes an excoriating attack on the cult of Sade amongst French left-wing or avant garde thinkers.“It is intellectually bizarre to make Sade a hero,” he says. “Even according to his most hero-worshipping biographers, this man was a sexual delinquent.”Mr Onfray says that a “myth” has been fashioned that Sade was a “libertarian, anarchist and revolutionary” – even a “feminist”. Not a bit of it, he says. Sade was an arrogant “feudal” aristocrat who thought that he had a right to torture and sexually abuse servants or beggars. His recorded exploits include the kidnapping and sexual torture of pre-adolescent serving girls.Period genre? Horror genre? Art genre?

Infamous? . . .

Following this antidote to the intellectualising of a period piece of art and horror, provided for by The Three Amigos, here is another case of: The spectacle of brutality used as deterrent can brutalise?

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma)

Among the numerous film adaptions of Sade's work, the most notable is Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, an adaptation of his infamous book, The 120 Days of Sodom.

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom is the 1975 period horror/art film directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. The film is a loose adaptation of the book The 120 Days of Sodom by the Marquis de Sade, set during World War II, and was Pasolini's final film, being released posthumously three weeks after his murder.

The film focuses on four wealthy, corrupt Italian libertines, in the time of the fascist Republic of Salò (1943–1945). The libertines kidnap eighteen teenagers and subject them to four months of extreme violence, murder, sadism and sexual and mental torture.

The film explores the themes of political corruption, consumerism, capitalism, nihilism, morality, abuse of power, social darwinism, sadism, sexuality and fascism.

Cinematic tour of the "Circles of Hell"!

The story is in four segments, inspired by Dante's Divine Comedy: the Anteinferno, the Circle of Manias, the Circle of Excrement, and the Circle of Blood. The film also contains frequent references to and several discussions of Friedrich Nietzsche's 1887 book On the Genealogy of Morality, Ezra Pound's poem The Cantos, and Marcel Proust's novel sequence In Search of Lost Time.

The Wikipedia article on this film cites Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader wrote of the film:"Roland Barthes noted that in spite of all its objectionable elements (he pointed out that any film that renders Sade real and fascism unreal is doubly wrong), this film should be defended because it 'refuses to allow us to redeem ourselves.' It's certainly the film in which Pasolini's protest against the modern world finds its most extreme and anguished expression. Very hard to take, but in its own way an essential work."

Stephen Barber writes:

"The core of Salò is the anus, and its narrative drive pivots around the act of sodomy. No scene of a sex act has been confirmed in the film until one of the libertines has approached its participants and sodomized the figure committing the act. The filmic material of Salò is one that compacts celluloid and feces, in Pasolini's desire to burst the limits of cinema, via the anally resonant eye of the film lens."Barber also notes that Pasolini's film reduces the extent of the storytelling sequences present in de Sade's The 120 Days of Sodom so that they "possess equal status" with the sadistic acts committed by the libertines. (Barber, Stephen (2010). "The Last Film, the Last Book". In Cline, John; Weiner, Robert G. (eds.). From the Arthouse to the Grindhouse: Highbrow and Lowbrow Transgression in Cinema's First Century. Scarecrow Press).

Enough? Or too much?

This is one of William Blake's Proverbs of Hell, proverbs that provide a useful guide to navigating ideological territories. Blake's Hell is the inverse of a Heaven, that in the scheme of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is where the seat of the "powers (and the ideas) that be" reside. But for Blake the "space" between these opposites can provide a "situation" for dialogue, and . . .

. . . where dialogue begins propaganda ends

And the potential for a "marriage", a dialogue between opposites, in this eighteenth century work by William Blake (1790-93), produced a couple of years before Sade's Philosophy in the Bedroom was published in 1795. Both of these works were informed by the contemporary revolutionary turmoil and reaction in France and across Europe. In their different ways Blake and Sade required strategies of one kind or another, in order to strip the veil from the body of TRUTH.

Twentieth century artists and philosophers produced their own methods for gaining awareness in ideological conditions that so totally shaped modern consciousness, as in deconstruction and détournement.

A détournement, meaning "rerouting, hijacking" in French, is a technique developed in the 1950s by the Letterist International, and later adapted by the Situationist International (SI), that was defined in the SI's inaugural 1958 journal as "[t]he integration of present or past artistic productions into a superior construction of a milieu. In this sense there can be no situationist painting or music, but only a situationist use of those means. In a more elementary sense, détournement within the old cultural spheres is a method of propaganda, a method which reveals the wearing out and loss of importance of those spheres."

It has been defined elsewhere as "turning expressions of the capitalist system and its media culture against itself" — as when slogans and logos are turned against their advertisers or the political status quo.

Détournement was prominently used to set up subversive political pranks, an influential tactic called situationist prank that was reprised by the punk movement in the late 1970s and inspired the culture jamming movement in the late 1980s.