The LODE Line Zone passes through Liverpool and is connected by the LODE and Re:LODE project to people and places along this pathway

LODE 1992 Re:LODE 2017

LODE Legacy

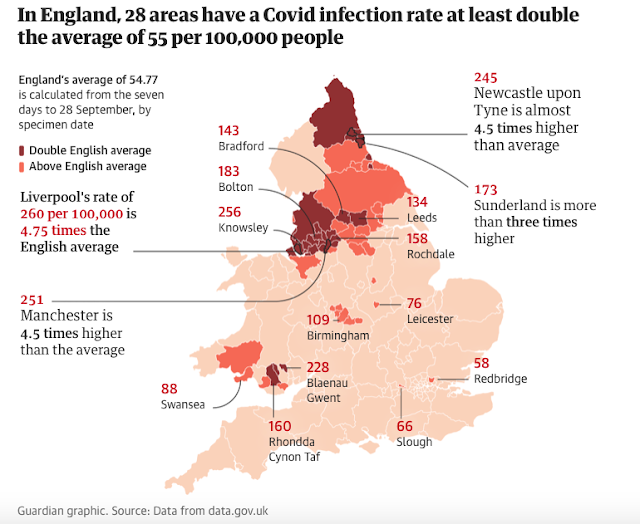

This map shows how on 1st October 2020 increased transmission rates of Covid-19 are distributed in concentrations of cases in parts of the Midlands, across the North West of England, North East England, South Wales and North Wales, parts of the central belt axis between Glasgow and Edinburgh in Scotland, and across Northern Ireland too. The current hot spots correspond to communities experiencing economic and social deprivation as well as the pandemic.

Liverpool and Knowsley recorded the highest infection rates in England. Cases are averaging more than 200 per 100,000 people across Merseyside – four times the England average.

Josh Halliday, North of England correspondent for the Guardian reports in the print edition of the Guardian, Thursday 1 October 2020, that:

Josh Halliday writes (Wed 30 Sep 2020):

The Merseyside economy may collapse and leave a legacy of poverty “for generations to come” without urgent financial support tied to new coronavirus restrictions, according to the region’s political leaders.Steve Rotheram, the metro mayor of the Liverpool city region, and six civic leaders, said Merseyside’s public finances were “at breaking point” and needed a “comprehensive package of financial support” from the Treasury when new lockdown measures are imposed.Additional restrictions are expected to be announced for Merseyside in the next 24 hours after Liverpool and Knowsley recorded the highest infection rates in England. Cases are averaging more than 200 per 100,000 people across Merseyside – four times the England average.Council leaders held a meeting with Chris Whitty, England’s chief medical officer, on Monday when a ban on households mixing was discussed.Measures that restrict social gatherings in pubs, bars, and restaurants – such as those introduced in part of north-east England – would have a particularly significant impact on the Merseyside economy given its reliance on hospitality and tourism. The industries account for half of the business rates that fund public services in Liverpool.In a joint statement, the political leaders said their local authorities had already incurred losses of more than £350m since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Senior figures believe more than 20,000 jobs could be lost in the hospitality industry by Christmas without urgent support.They said: “We are already at breaking point. With new restrictions – and who knows for how long they might be needed – our economy and public services may collapse. If we do not act now, we will see a legacy of unemployment and ill-health that will cost lives for generations to come. So, today, we are calling on the government to work with us.“If government decide that new restrictions are required, they must also provide a comprehensive package of financial support for our economy and our public services.”The joint statement was signed by Rotheram, the Liverpool mayor, Joe Anderson, the leader of Knowsley council, Graham Morgan, the leader of Sefton council, Ian Maher, the leader of St Helens council, David Baines, and the leader of Wirral council, Janette Williamson.The leaders also called for an “immediate uplift” in testing capacity to match its rising cases. There has been concern that local authorities are losing control of the virus owing to a shortage of tests. Many council leaders believe the daily case data no longer provides an accurate representation of how widespread the disease is.

Josh Halliday follows up on this story with a report (The 1 Oct 2020) on further developments on the health, social and economic impact of the pandemic in Liverpool, Warrington and Teeside, and how the:

Middlesbrough mayor vows to defy government over new Covid restrictions

Josh Halliday writes under the subheading:

Threat made as Matt Hancock announces latest lockdowns in Merseyside, Warrington and Teesside

More than 2 million people in Merseyside, Warrington and Teesside will be banned by law from mixing with other households indoors in the latest extension of lockdown restrictions, as Middlesbrough’s mayor took the extraordinary step of saying he was prepared to defy the government.The measures were announced as coronavirus cases continued to rise sharply in the north-west and north-east of England.The new rules mean it will be illegal from Saturday for nearly 5 million people in those regions to meet others they do not live with in all indoor settings, including pubs, bars and restaurants. Similar rules came into force elsewhere in the north-east earlier this week.The health secretary, Matt Hancock, said: “I understand how much of an imposition this is. I want rules like this to stay in place for as short a time as possible, I’m sure we all do.“The study published today shows us hope that together we can crack this, and the more people follow the rules and reduce their social contact, the quicker we can get Liverpool and the north-east back on their feet.”Hancock said a £7m support package would be made available to each of the affected councils. There was an immediate backlash from local leaders, who called the financial help “a drop in the ocean”. Middlesbrough’s mayor took the extraordinary step of saying he rejected the new measures and was prepared to defy the government.Andy Preston, the independent mayor of Middlesbrough council, said his authority and Hartlepool council had asked for a ban on households mixing in their own homes, but that the government’s measures went much further. They were based on “factual inaccuracies and a monstrous and frightening lack of communication, and ignorance”, he said. “As things stand, we defy the government and we do not accept these measures.”He later said he would not condone anyone disobeying the new law, the BBC reported.Mike Hill, the Labour MP for Hartlepool, said he was “totally angered” by the government’s “absolutely disgraceful one-size-fits-all approach”.The restrictions also caution against all but essential travel on public transport and attendance at amateur or professional sports events. Visits to care homes should only take place in exceptional circumstances.Merseyside’s 14 Labour MPs, six council leaders and the mayor of the Liverpool city region, Steve Rotheram, said they welcomed the action being taken, but questioned whether it was enough to contain the virus.They said they were seeking urgent talks with the government to understand the scientific evidence behind the restrictions and to plead for a significant cash injection to prevent economic disaster.Liverpool council estimates that its budget deficit is £45.6m in a best-case scenario because of coronavirus, rising to £66m in a worst-case scenario.Liverpool’s mayor, Joe Anderson, said he recognised that the infection rate was “basically out of control”, but added that hotels, bars and restaurants were in danger of closing.He told BBC Merseyside: “It’s nowhere near enough. £7m wouldn’t be enough for Liverpool alone, let alone across the city region. It’s got to be in the hundreds of millions that we need to support businesses to survive just for a matter of weeks.”Hancock also announced the reopening of Bolton’s hospitality industry, two days after the town’s Conservative council leader told the Guardian that the area had been “forgotten” since its pubs, restaurants and bars were restricted to takeaway-only trade three weeks ago.Jonathan Ashworth, the shadow health secretary, said he supported the new measures, but that areas needed urgent financial support. Otherwise, “existing inequalities, which themselves have a health impact and allow the virus to thrive, will be exacerbated”, he said.“People need clarity as well. Areas like Leicester, Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, Bradford have had restrictions imposed on them for months now. Millions of people in these local lockdown areas just need some reassurance that an end is in sight.”Hancock was unable to say when restrictions would be lifted in those areas, but said the measures were “vital for suppressing the virus”.Coronavirus cases in Merseyside are averaging more than 200 per 100,000 people, more than four times England average across England. Liverpool and Knowsley have the highest infection rates in England.Measures that restrict social gatherings in pubs, bars and restaurants, such as those introduced in part of north-east England, will have a particularly significant impact on the Merseyside economy, given its reliance on hospitality and tourism. The industries account for half of the business rates that fund public services in Liverpool.Rotheram and six civic leaders said Merseyside’s public finances were at breaking point and needed a “comprehensive package of financial support” from the Treasury.

The pandemic has exposed the structural and systemic social and health inequalities across the economies of a world dominated by global capitalism

Across England, the stark geographical concentrations of Covid-19 cases in areas of economic and social deprivation expose north south divides of long standing.

Niamh McIntyre and Josh Halliday report for the Guardian on some troubling data (The 1 Oct 2020) under the headline:

Covid cases doubled under most local lockdowns in England

Niamh McIntyre and Josh Halliday write under the subheading:

Exclusive: Confusing rules blamed for rise in infections in 11 of 16 towns and cities under long-term restrictions

Coronavirus cases have doubled in the majority of English cities and towns that are subject to long-term local lockdowns, Guardian analysis has found, amid growing concern that restrictions are confusing and done “on the cheap”.

In 11 out of 16 English cities and towns where restrictions were imposed nine weeks ago, the infection rate has at least doubled, with cases in five areas of Greater Manchester rising faster than the England average in that time.

In Wigan, cases have risen from seven per 100,000 residents to 102 in that period. Leicester is the only one of the 16 areas to record fewer cases than when the measures were implemented.

The findings will raise concerns after Prof Chris Whitty, the chief medical officer for England, said the government’s strategy was to limit the virus to regional hotspots. “If everybody follows the guidance, then we could actually contain it within the areas it is [now] in the way that happened to some degree in Italy and Spain,” he said at a press conference on Wednesday.

On Thursday, more than 2 million people in Merseyside, Warrington and Teesside were told they were to be banned by law from mixing with other households indoors. However, the mayor of Middlesbrough, Andy Preston, said he would not accept the measures because they were based on “factual inaccuracies and a monstrous and frightening lack of communication, and ignorance”. He added: “As things stand, we defy the government and we do not accept these measures.”

Scientists, MPs and local leaders said the growing patchwork of local measures – which now cover about 20 million people, nearly a third of the UK population – had failed to bring down coronavirus rates, in part because the rules were unclear.

There is concern that large parts of the country could be left with tighter restrictions for months after George Eustice, the environment secretary, said measures would only be lifted when local infection rates were “more in line with the national trend”.

Analysis shows that 28 areas of England, comprising nearly 9 million people, have double the country’s average infection rate of 55 cases per 100,000 people, including Leeds, Manchester, Bradford and Liverpool.

Sir Chris Ham, a former chief executive of the King’s Fund thinktank, said the figures showed that the government must “redouble its efforts in generating public support for restrictions and using a wide range of community leaders to do so”.He said case numbers were not falling because the lockdown rules were too “complex and confusing”, there was a lack of support for people self-isolating, and the test-and-trace system was “still not working well enough”.Using Public Health England data, the analysis measured the increase in case rates since restrictions were introduced in each area until the week ending 20 September. It excluded lower-tier local authorities and areas where lockdowns had been introduced in the previous two weeks.Cases in Wigan, Bolton and Bury had roughly quadrupled since restrictions were imposed on 31 July, a significantly faster rise than in the rest of England.The rise in cases is now affecting hospital wards. The number of admissions from Covid has nearly doubled in Greater Manchester since the measures were introduced, rising from 25 a day in the first week of August to 49 earlier this week. The number of Covid patients in intensive care in the area has jumped from 12 to 41.While it is not possible to know how high case numbers would have risen if no action had been taken, scientists said that if the aim was to bring down infection rates, local lockdowns had failed.Boris Johnson cited Luton on Wednesday as an example of local lockdowns working. Although its cases did fall when restrictions were imposed, allowing it to be released from the measures within days, they have since started rising and are now above their original level.Cases in most places continued to rise after lockdown restrictions were imposed

Guardian graphic. Source: Public Health England Surveillance reports. Note: Stockport and Wigan had restrictions lifted and subsequently reimposed, but this is not represented due to a time lag in PHE data. Parts of Bradford and Blackburn with Darwen also had lockdowns lifted and reimposed, not shown due to some parts of these areas being in lockdown consistently

Dr David Strain, a senior clinical lecturer at the University of Exeter and an honorary NHS consultant, said he believed another national lockdown was a “very realistic possibility” due to the failure to stamp out the disease before autumn. “The lack of clarity about what the rules are is a big part of the problem. We need very good, clear and consistent messaging across the board that we should minimise the spread by creating exclusive social bubbles.”

Andy Burnham, the mayor of Greater Manchester, said ministers had tried to contain the virus “on the cheap” by introducing local restrictions without a significant package of financial support for businesses, residents and local authorities.He said he would not want the rules to be tightened further in Greater Manchester; rather, they needed to be “more consistent”. “There is still a feeling that local restrictions only achieve so much and actually it’s only going to be anything [imposed] nationally that bring cases back down again,” he said.Matt Hancock, the health secretary, on Thursday announced a £7m payment for councils in affected areas, while some local authorities, such as Bolton, have been allowed to hand out up to £1,500 per business every three weeks. But local leaders described this as a “drop in the ocean”, calling instead for an extension of the furlough scheme for businesses in lockdown areas.

Looking to the future . . .

. . . and misrepresenting the past?

The image above is of Another Place on Crosby beach in Sefton, Merseyside, and some of the sculptural works by Antony Gormley that were installed here as a temporary commission by Lewis Biggs, then director of Liverpool Biennial, back in 2005, but still here, in situ by popular demand. In the background a wind farm, off the Sefton and Wirral coastline of Liverpool Bay, is clearly visible in the photo.

Offshore wind . . .

. . . and the windbag!

Boris Johnson's speech to the "virtual" Conservative party conference

Q. What did Boris Johnson's conference speech really mean?

So runs the headline for an analysis of the Conservative conference 2020 by Peter Walker, political correspondent for the Guardian (Tue 6 Oct 2020).

Boris Johnson’s speech at Conservative conference drew on a number of themes, and was as notable for what it did not talk about as what it did. Here were the main ideas, and the arguments behind them.

CoronavirusWhat he said: “I don’t know about you, but I have had more than enough of this disease that attacks not only human beings, but so many of the greatest things about our country.”The background: Conference speeches tend to be light on detail, and Johnson’s survey of Covid-19 was a particularly blancmange-like mix of jokes about visor-wearing hairdressers dressed “as though they are handling radioactive isotopes” and a sober acknowledgement that the UK has “mourned too many”.The PM was keen to stress his hope for a relatively quick return to a more normal life, and the watching Tory faithful would expect the speech to focus more on optimism than specifics about test-and-trace. But Johnson has previously been bullish about an end to many restrictions by Christmas, which is very obviously not going to happen. There are only so many more times he can get by just on blithe confidence.A post-Covid worldWhat he said: “In the depths of the second world war, in 1942, when just about everything had gone wrong, the government sketched out a vision of the postwar new Jerusalem that they wanted to build. And that is what we are doing now – in the teeth of this pandemic.”The background: Johnson is the latest politician to make this parallel. Ed Miliband summoned up the image of the reforming Clement Attlee government as a model for a green transformation for the economy. The PM was less specific, mainly saying a key goal would be to boost growth. It was notable how he compared this with the last “12 years of relative anaemia” – 10 of which have been under Conservative prime ministers.His own healthWhat he said: “I have read a lot of nonsense recently, about how my own bout of Covid has somehow robbed me of my mojo … I could refute these critics of my athletic abilities in any way they want: arm-wrestle, leg-wrestle, Cumberland wrestle, sprint-off, you name it.”The background: A good rule of thumb about whether criticism of a politician has hit home is how earnestly they rebut it. While Johnson was typically colourful in his language, this section shows how the PM is worried about the impression of someone waylaid by long-term symptoms following his serious brush with Covid-19. This ties into the narrative of a broad-focus leader for the good times struggling with the serious, detailed logistics of a global pandemic, and potentially set to stand down soon. Johnson spoke again how his weight could have exacerbated his symptoms, saying he has now shed almost two stone.Wind power and green issuesWhat he said: “I can today announce that the UK government has decided to become the world leader in low cost clean power generation … and we believe that in 10 years’ time offshore wind will be powering every home in the country.”The background: Perhaps the one real policy idea in the speech, this was the element trailed in advance. While the amounts pledged so far have been dismissed as nowhere near enough for this wind-powered transformation, it is notable in the longer context for a Conservative leader to focus on clean energy, let alone wind turbines, which for years has been an object of derision, even hate, for many in the party.Role of the private sectorWhat he said: “We must be clear that there comes a moment when the state must stand back and let the private sector get on with it … We must not draw the wrong economic conclusion from this crisis.”The background: A general nod to the concerns of the Tory faithful about the massive state response to the coronavirus pandemic and the colossal levels of borrowing this brought. Consider this just a statement of intent, and one which could easily get abandoned amid the tough economic realities of the coming months and years.Culture warsWhat he said: “We are proud of this country’s culture and history and traditions; they literally want to pull statues down, to rewrite the history of our country, to edit our national CV to make it look more politically correct.”The background: Complete with a dismissive mention of “lefty human rights lawyers and other do-gooders”, this was Johnson on what he still sees as strong political ground, contrasting his embrace of tradition with Labour’s supposed metropolitan effeteness on such matters. Whether it hits home is another matter, given Keir Starmer’s embrace of patriotism in his own conference speech, and the Labour leader’s disinclination to dig himself into the trenches on such issues.BrexitWhat he said: “Be in no doubt that they are secretly scheming to overturn Brexit and take us back into the EU.”The background: The dog that did not bark. Aside from this mention of Labour’s supposed – and not actually true – desire to stop Brexit, Johnson barely mentioned the defining issue of the 2019 election. Why? One possibility is the type of Brexit discussion that would thrill the watching membership might also annoy the EU at a crucial time for talks about a departure deal the PM still wants to seal.PoliciesWhat he said: “We will fix the injustice of care home funding, bringing the magic of averages to the rescue of millions” … “explore the value of one-to-one teaching, both for pupils who are in danger of falling behind, and for those who are of exceptional abilities” … “this government is pressing on with its plan for 48 hospitals – count them”.The background: Light on detail even by the standards of conferences speeches, the plan for care homes was, literally, just a sentence, and a particularly opaque one. Similarly, there were no clues about how one-to-one teaching could be funded, or achieved amid an ongoing recruitment shortfall. As of this week we do have some facts about the hospital building programme – that the majority will not happen until as late as 2030, and most projects are rebuilds or new wings.

Build Back Better?

Never mind the bollocks . . .

. . . Boris Johnson has said in his speech to the Conservative party conference that Britain must not return to the status quo after the coronavirus pandemic, promising a transformation akin to the 'New Jerusalem' the postwar cabinet pledged in 1945.The prime minister also mounted a robust defence of the private sector, saying 'free enterprise' must lead the recovery and that he intended to significantly roll back the extraordinary state intervention that the crisis had necessitated.

The wartime government of Winston Churchill was a coalition government with the politically and technocratically skilful and competent Labour party ministers in the cabinet. The capacity and capability of the state will always outperform 'free enterprise', as clearly evident today with the so-called "NHS" Test and Trace fiasco, and which is a private enterprise driven disaster.

The 1945 Labour landslide election result made it possible for the founding of the National Health Service and the beginning of the implementation of universal social security measures that, more recently, have been stripped away by a Conservative government and its policy of ten years of austerity, the bedroom tax and the failure of "universal credit".

When it comes to a new Jerusalem, whoever came up with the concept knows it could prove a useful lead in to recent culture war territories. Re:LODE Radio references the recent opportunistic distraction, by distraction, from distraction, of the sung, or unsung, last night of the Proms.

William Blake's PREFACE to Milton

We do not want either Greek or Roman Models if we are but just & true to our own Imaginations

The date of the printing plate of William Blake's "Preface" to the "Prophetical" illuminated bookwork Milton is 1804, although the work was published four years later in 1808. It is from this page of text that the text of And did those feet in ancient time first appears. It follows a preface text full of Blake's anger and "unpleasantness" (a positive quality in Blake according to T. S. Eliot), an invective against the establishment of his own time. Boris Johnson, a man without qualities, typically apes the "classic" pose with his "posh quotes", something that Blake would detest and deride, as the false interpretation of the "classics". This is a continual theme in Blake's work.

Today this text is best known as the lyric of the hymn "Jerusalem", with music written by Sir Hubert Parry in 1916. The famous orchestration was written by Sir Edward Elgar, composer of "Land of Hope and Glory".

The Composer of 'Land of Hope and Glory' Would Have Hated Everyone Buying It Today, says Jack Davies (26 August 2020) writing on Vice. He suggests that today "Edward Elgar's composition has become the latest battleground in the reactionary right's culture wars, but the man himself was totally at odds with the British society that has come to venerate him".

Stewart Lee, as usual, cuts through the influence machine of a Conservative Rightwing Aided by the Press (or CRAP), with this Opinion piece, published just over a month ago (Sun 6 Sep 2020) in the Observer New Review, and headlined: The divided land of 'woke' and Tory, and with the subheading: The rightwing press is practised at poisoning our politics with confected outrage

Writing last weekend on the scandal surrounding the Proms’ absence of patriotic songs, the former minister of fun David Mellors opined, “the person I feel most sorry for is Edward Elgar”, the composer of Land of Hope and Glory. Not black Britons offended by Rule, Britannia!’s references to slaves; not black Britons annoyed by people taking offence on their behalf; and not the blameless female Finnish conductor suffering death threats for, in Mellors’s words, “uttering a load of woke nonsense about Black Lives Matter”. No. Who’s the most oppressed minority in the world today? Dead, white, male Victorian composers! And Laurence Fox!!

I felt sorry for Elgar too. In 1998, I worked with Keith Harris, the ventriloquist famous for Orville the Duck. But Harris told me he now hated “that bloody bird”, regarding it as an albatross even though it was a duck. By 1918, according to unsubstantiated “diary” extracts published in the Daily Mail in 2018, Elgar hated Land of Hope and Glory too, writing, “I went to the Coliseum and they played Land of Hope and Glory not once, but twice; the whole audience joined in. I could not. I regret very profoundly how this song has become an anthem to war… I am awfully tired of it.” Elgar would have been delighted to see his piece abandoned, just as Harris would have liked to see his puppet duck dismembered by a puppet fox, perhaps Basil Brush, violent when drunk. I hope Elgar and Harris, haunted by their Frankingsteins, can comfort each other in heaven somehow.

I read of Mellors’s misguided sympathies in last weekend’s Mail on Sunday, in the Coach and Horses in Pinvin, Worcestershire. I had walked the Malvern hills alone on my final Covid summer expedition, Elgar undulating on my iPod, saturating the landscape he loved. I tried to understand the Great Proms Patriotism Scam, a turbo-charged Brexit era version of the Great Winterval Hoax of 1997-1999, when the rightwing press falsely claimed Birmingham city council would chemically castrate any white people who wished anyone a Merry Christmas. The Winterval Hoax later featured in the Leveson inquiry into newspaper ethics, an Elastoplast on a severed artery. The Tory press poisons our discourse as deliberately as Russia poisons politicians. Both escape justice.

Building Jerusalem?

Re:LODE Radio supposes that Boris Johnson's version of building back a better Jerusalem will prove more PR than effort and achievement, and unlikely to echo the ambitions of the nineteenth century urban renewal programmes as set out in Tristram Hunt's Building Jerusalem.

For Boris Johnson, Jerusalem, the hymn that isn't a hymn, or the best national anthem we have never had, has got nothing to do with William Blake, but everything to do with English, and NOT British, exceptionalism. And it's "pie in the sky" when we are all gone.

John of Patmos watches the descent of New Jerusalem from God in a 14th-century French tapestry

According to the curious mythology surrounding this text is that Blake's poem was supposedly inspired by the apocryphal story that a young Jesus, accompanied by Joseph of Arimathea, a tin merchant, travelled to what is now England and visited Glastonbury during his unknown years. This improbable occurrence emerges in mythology created in the period of British imperial ascendancy, as has been identified and questioned by A.W. Smith, who concluded that "that there was little reason to believe that an oral tradition concerning a visit made by Jesus to Britain existed before the early part of the twentieth century".

For Blake the poem's theme is linked to the Book of Revelation (3:12 and 21:2) describing a Second Coming, wherein Jesus establishes a New Jerusalem.

In the most common interpretation of the poem, Blake implies that a visit by Jesus would briefly create heaven in England, in contrast to the "dark Satanic Mills" of the Industrial Revolution. Blake's poem asks four questions rather than asserting the historical truth of Christ's visit. Thus the poem merely wonders if there had been a divine visit, when there was briefly heaven in England. The second verse is interpreted as an exhortation to create an ideal society in England, whether or not there was a divine visit.

A green and pleasant land?

William Blake lived in London for most of his life, but wrote much of Milton while living in the village of Felpham in Sussex.

Blake's poem offers an inevitable interpretive contrast for a modern reader between dark Satanic mills on one side, and a green and pleasant land on the other, full of green pastures and overlooked by clouded hills. Blake's Satanic mills may well have been linked to the fate of the Albion Flour Mills in Southwark, the first major factory in London. This rotary steam-powered flour mill, engineered by Matthew Boulton and James Watt, could produce 6,000 bushels of flour per week.

The factory could have driven independent traditional millers out of business, but it was destroyed in 1791 by fire, perhaps deliberately. London's independent millers celebrated with placards reading, "Success to the mills of Albion but no Albion Mills."

Opponents referred to the factory as satanic, and accused its owners of adulterating flour and using cheap imports at the expense of British producers. A contemporary illustration of the fire shows a devil squatting on the building. The mills were a short distance from Blake's home in Hercules Road, Lambeth. This common interpretation stereotypically casts the modern industrial and urban landscape as an image of hell, and the green pasture as the fields of heaven.

In the late eighteenth century the green and pleasant land of England was rife with conflict, poverty and injustice, as a result of landowners enclosing common land by acts of "their parliament", and the consequences of an agrarian revolution that swept away hitherto sustainable livelihoods on the land. There was a dark side to the landscape.

Detail from Manchester from Kersal Moor, by William Wyld, 1852

But these days mapping "Toryland" is no longer a simple matter, and neither is it obvious that industrial cities are a natural "Labour heartland". It's complicated.

Green fields and the 'red wall'

Across the LODE Zone pathway from Liverpool to Hull, when it comes to uninformed and presumptuous political stances, the usual stereotypes won't do. It is complicated. The "red wall", also referred to as Labour heartlands and Labour's red wall, is a term used in the politics of the United Kingdom to describe a set of constituencies in the Midlands, Yorkshire, North East Wales and Northern England which historically tended to support the Labour Party. The term was coined in 2019 by pollster James Kanagasooriam. When viewed on a map of previous results, the block of seats held by the party resembled the shape of a wall, coloured red, which has traditionally been used to represent Labour.

2017 election results and the red wall

The red wall metaphor has been criticised as a generalisation. Lewis Baston argues that the "red wall" is politically diverse, and includes bellwether seats which swung with the national trend, as well as former mining and industrial seats which show a more unusual shift.

In 2014, political scientist Matthew Goodwin and Robert Ford documented the erosion by UKIP of the Labour-supporting working-class vote in Revolt on the Right.

In the 2017 UK General Election, the Conservatives lost seats overall, but did gain six previously safe Labour seats in the Midlands and North: NE Derbyshire, Walsall North, Mansfield, Stoke-on-Trent South, Middlesbrough South & East Cleveland and Copeland (held from the 2017 Copeland by-election). In 2019, the Conservatives increased their majority in the seats previously gained.

Conservative gains across the LODE Zone in the 2019 UK General Election

Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage has suggested prior support of many northern Labour voters for UKIP and the Brexit Party made it easier for them to vote Conservative.

In the 2019 general election, the Conservative Party gained 48 seats net in England. The Labour Party lost 47 seats net in England, losing approximately 20% of its 2017 general election support in red wall seats. All of these seats voted to leave the EU by substantial margins, and Brexit appears to have played a role in these seat changes.

Voters in Bolsover and swing voters of the type thought to be typified by Workington man cited Brexit and the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn as reasons why they chose not to vote Labour. Labour lost so much support in the red wall in some seats, like Sedgefield, Ashfield and Workington, that even without the vote increase for the Conservatives, the Conservatives would have still have taken those seats.

Labour’s lost working-class voters have gone for good

So Chris Bickerton asserts in his Opinion piece for the Guardian (Thu 19 Dec 2019) following the UK General Election.

Chris Bickerton writes under the sub heading:

British politics post-Brexit will be no kinder to a party that has taken supporters for granted, particularly in the north

This is an extract from Chris Bickerton's Opinion piece:

Is the Labour party dying? It’s a question that commentators have asked since the devastating election defeat last week. But in fact, as a party of working-class self-representation, Labour is already dead.

Throughout much of the 20th century, there were parts of northern England where jobs came with firm expectations about Labour party membership. Labour, the unions and the nonconformist churches were the great social institutions of 20th-century working-class politics. Secularisation in the 1960s saw the decline in the role of the church. Then the unions were dismantled in the 1980s. Now the Labour party, as we once knew it, is gone. Constituencies that had been held by Labour almost since the modern two-party system was born – such as Don Valley and Wakefield – have voted in the Tories.

Change does not happen overnight. The roots of the present defeat take us back several decades. Labour’s dramatic victory of 1997 was built upon a shift in the composition of the Labour vote: more middle class, more concentrated in the home counties. In the 2000s, Ukip’s rise was widely seen as a threat to the Tory vote. But as Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin documented so well in Revolt on the Right, Ukip was also starting to erode the working-class Labour vote. It shifted from its origins as an anti-EU party, criticising instead the government’s commitment to an open labour market and its embrace of EU free movement rules. Lacking real debate within Labour, the immigration issue became a symbolic one for voters, exemplifying the detachment of the London leadership from grassroot concerns.

But all is NOT lost . . .

. . . it's complicated though.

Modern, multicultural and surprisingly liberal: this is the real 'red wall'

So says John Harris in his Opinion column for the Guardian Journal (Sun 4 Oct 2020).

Opinion illustration for John Harris: Matt Kenyon for the Guardian

John Harris writes:

The election of 2019 and the political climate surrounding it now feel like relics of a different age. But one of the key elements of those distant weeks has stuck around: the concept of the red wall, a byword for the post-industrial places in the Midlands, the north of England and north Wales that were once solidly loyal to Labour but now have new Conservative MPs.

In the Guardian, Keir Starmer’s speech to Labour’s virtual conference was framed as urging “red-wall voters to ‘take another look at Labour’”. Last week, protests by north-east Tory MPs about Covid restrictions were characterised as a “red wall revolt”, while government plans to abolish district councils boiled down to an attempt to “shore up the red wall”.

For anyone curious about our new politics, there is the pollster Deborah Mattinson’s recent book Beyond the Red Wall, the fascinating story of encounters with voters in three such places.

Starmer and his people may be determined to revive Labour’s bond with these areas, but elsewhere on the political left, there is unease about the red wall’s sudden centrality. In some people’s view, Labour’s new attempt to begin a conversation with voters there by emphasising family and patriotism – themes Starmer returned to in Sunday’s interview with the Observer – risks “pandering”. There are suggestions that some former Labour heartlands are so reactionary that progressive politics should simply accept their loss and move on. These views reflect a received wisdom in our politics since the referendum of 2016: the idea of an England supposedly split clean in two.

We all know the drill by now. Urban places are held to be liberal, future-facing and welcoming of immigration and cultural diversity. By contrast, the red wall and provincial England are supposedly authoritarian, nostalgic, monocultural and bigoted. This perhaps handily positions a sizable share of the country to the Tory side of a culture war, which recent reports suggest will be based around everything from alleged BBC bias to trans rights, to shipping asylum seekers around the world.

Such provocations may demonstrate that politics has irrevocably changed, and voters have permanently realigned – and if that’s true, Starmer’s efforts to calm things down and appeal to people on either side of an unbridgeable divide will probably be doomed.

Yet, as the old David Bowie song goes, this is not America, and the red wall is far from a Trumpian redoubt of hard-right politics. Its new relationship with Boris Johnson’s Tory party feels tentative and provisional, as was evident in plenty of the conversations I had with Labour-Conservative switchers last December and embodied by an exchange with a man in Stoke-on-Trent who had just backed the Tories for the first time in his life, just before the polls closed. How did it feel, I wondered. His face screwed into a grimace. “Not good,” he said.

People had – and still have – a sense of the Labour party being distant and condescending (Mattinson’s book captures people in red-wall constituencies seeing Labour as a party of “naive and idealistic middle-class students … arrogant kids boasting degrees but lacking life experience”), and biting disdain for Jeremy Corbyn. And when it came to Brexit, there was also a moral sense of an agreement that had not been honoured. “We voted three years ago, and it’s still not happened,” a man in the Nottinghamshire former mining town of Worksop told me. His wife then chipped in: “What’s the point in having a democratic country if they’re not going to listen to the word of the voters?”

Told to make a choice, people had done so, and then watched as the winning option failed to materialise. Such was the incisive appeal of “Get Brexit done”: the fact that someone heeded the call does not automatically put them in the same ethical and political category as, say, Nigel Farage.

Red-wall areas are not really the hidebound, reactionary places of some people’s imagination. Many large places there – Walsall, Wolverhampton, Stoke-on-Trent, Bolton, Bury – are diverse and, in their own way, quintessentially modern. As they do everywhere else, attitudes in such places vary according to age, but the liberalising transformations that have changed society – on race, gender and sexuality – since the 1960s are often clear, even among people others might see as being stuck in the past. As Sunder Katwala, the director of the thinktank British Future, puts it: “The social conservatives of 2020 are probably as or more liberal as the social liberals of 1990.” Whatever has happened recently in the red wall, he warns against interpreting it as a backlash “against modern life and all of the gains of social liberalism in the last half-century”.

Yes, people in such places voice anxieties and resentments about immigration and the benefits system. These views clearly fed into the vote to leave the EU and some people’s recent support for the Conservatives, and they can sometimes be ugly and nasty. But these opinions are often impossible to disentangle from such on-the-ground issues as housing shortages and pitiful work opportunities. This is not to deny the existence of straight-up racism and other prejudices; the point is that most human beings are more open and accepting than they are often given credit for, and focused on the daily grind rather than furores that might be convulsing social media.

A recent quote on the Vice website from a newly elected Tory MP speaks volumes: “There’s an interesting view by some within the party that red-wall seats will automatically not be as pro-LGBT. That’s nonsense. People in red-wall seats in general just want to be allowed to get on and live their damn lives … and they want everyone else to live their lives freely.”

On the other side of England’s divide, cities are equally full of nuance. It is worth remembering that in the 2016 referendum, a third of Asian voters supported leave (among black voters, the figure was 27%). Three-quarters of people who belong to an ethnic minority say they have a strong British identity (a trait they share with white non-graduates, and which is less prevalent among white left-leaning graduates). It is easy to ignore the social conservatism of many black and Asian voters, and the fact that some of them may be as open to certain narratives about family and country as white people.

Everywhere, complexities abound. When I was a reporter, the first interviewee I ever recorded talking about latter-day immigration “opening the floodgates” was a senior Muslim community figure in Leicester. In the buildup to the referendum, the place that convinced me leave might win was Handsworth in Birmingham, where South Asian businesspeople talked about voting for Brexit in terms of national and personal self-reliance. Of course, there was no implication of any affinity with the nativist right. But again, what people said highlighted the fact that values and attitudes are more mixed up than some accounts of stark, binary divisions suggest.

Given that basic fact, it should not be hard to conceive of a left-leaning politics that begins to speak to people on the various sides of our national divides, not least after the pandemic has so vividly exposed Britain’s deep social and economic inequalities, and the decades wasted by leaving them unchecked. The red wall is not lost to the Tories, nor as distant from the rest of the country as we might think. If we want rid of this grim government, moreover, our estrangements and divisions demand not to be accepted, but healed.

John Harris reviewed Deborah Mattinson's recent book Beyond the Red Wall in this Book of the day book review on Politics books for the Guardian, along with Tom Hazeldine's The Northern Question (Thu 24 Sep 2020).

This is an extract from John Harris's review, with particular reference to Beyond the Red Wall:

Deborah Mattinson’s Beyond the Red Wall is all about life and politics in the latter kind of place. As a pollster who once worked for Gordon Brown, she specialises in focus groups, and her latest book is centred on what people have gathered to tell her in Stoke-on-Trent, Darlington and Accrington. Somewhat inevitably, her narrative gives the impression of someone flitting in and out of such places, but her material is both fascinating and sobering – full of loss, resentment and the sense of politics suddenly being turned upside down. Contrary to Kanagasoorium’s suggestion about the degradation of memory, moreover, it implies that the north-south divide might denote something not just cultural, but almost philosophical: the difference between people who want to live with a kind of future-facing weightlessness, and those connected to the industrial past, and proud of it.

According to the people Mattinson gathers together, Labour is now a party of the south, simultaneously the representative of “losers and scroungers”, but also “naïve and idealistic middle-class students … arrogant kids boasting degrees but lacking life experience”. It is telling, too, that the party is seen by some as “Keeping everyone down and dependent on them”: not a force that addresses inequality, but one that sustains it, in its own political interests.

What do the people she calls “Red Wallers” want? Mattinson summarises the views of two men in Accrington, who want to “shift power north and end the north–south divide: make the Northern Powerhouse really happen; get all industries working together” and “bring investment back into this part of the world again”. This suggests the basis of potential agreement with the more socially liberal voters who represent Labour’s new core support, but the book also details what would get in the way – chiefly, a string of grimly familiar views about immigration and the benefits system. In March this year, Mattinson assembled in a Manchester hotel a group of people split between “Red Wallers” and “Urban Remainers”: despite regular outbreaks of consensus, wildly divergent values were expressed. Yet what her account perhaps fails to grapple with are the political complexities around age. Her most voluble subjects seem to be well over 30, and you occasionally wonder if Labour’s Red Wall woes might be eased by the simple passage of time.

Boris Johnson receives warm reviews during Mattinson’s conversations in the Tories’ new territories. “He’s said that he’ll get Brexit done, that he’ll end the north-south divide, and now, that he’ll deal with this Coronavirus thing,” an unnamed resident of Darlington tells her. “We’ll see, but he seems pretty confident to me, and I like that in him.” What an era of north-south tensions has led to, it seems, is not just politics being transformed, and an expression of popular affinity with a man whose middle name is De Pfeffel, but a huge expectations problem. If I were a Tory reading those words, I would feel more than a frisson of fear.

Promises, expectations, delivery?

PM pledges to to transform country in keynote address to Conservative party conference

Jessica Elgot, Deputy political editor at the Guardian reports on Boris Johnson's transformative vision for the United Kingdom (Tue 6 Oct 2020). She writes in her report of Johnson's view that:

“The UK economy had some chronic underlying problems: long-term failure to tackle the deficit in skills, inadequate transport infrastructure, not enough homes people could afford to buy – especially young people – and far too many people, across the whole country, who felt ignored and left out, that the government was not on their side. And so we cannot now define the mission of this country as merely to restore normality.”

Reiterating his pledge to recruit 20,000 new police officers, Johnson criticised the legal profession, saying his government would stop the criminal justice system from being “hamstrung by what the home secretary would doubtless, and rightly, call the lefty human rights lawyers and other do-gooders”.

Though Johnson underlined how he expected the private sector to be at the forefront of the economic recovery, his speech outlined many new public spending commitments – including the introduction of one-to-one teaching for both gifted and struggling students, as well as the overhaul of social care.

“We will fix the injustice of care-home funding, bringing the magic of averages to the rescue of millions,” he said. “Covid has shone a spotlight on the difficulties of that sector in all parts of the UK, and to build back better we must respond; care for the carers as they care for us.”

However, he said free enterprise would be at the heart of future growth, a key theme of previous Johnson speeches, and sounded an early warning about the extent of state intervention on schemes such as furlough. He said Rishi Sunak had “done things that no Conservative chancellor would have wanted to do except in times of war or disaster”.

“There comes a moment when the state must stand back and let the private sector get on with it,” he said. “We must not draw the wrong economic conclusion from this crisis.”

He said the state would help the private sector by “becoming more competitive, both in tax and regulation”.

The prime minister also set out plans briefed by Downing Street overnight to power every home in the UK with offshore wind energy within a decade, a move he said would create “hundreds of thousands, if not millions of jobs” in the next decade.

He added that the UK would “become the world leader in low-cost, clean power generation – cheaper than coal and gas”, comparing its offshore wind resources to Saudi Arabia’s oil wealth.

Johnson was a prominent critic of wind power during his career as a columnist, and joked in his speech that “some people used to sneer at wind power 20 years ago and say that it wouldn’t pull the skin off a rice pudding”, a phrase he himself used.

Downing Street said the initial investment would rapidly create about 2,000 construction jobs and enable the sector to support up to 60,000 jobs directly and indirectly by 2030 in ports, factories and the supply chains.

In a nod to Tory backbenchers who have threatened to vote down any future curbs on freedoms because of the pandemic, Johnson said he hoped there would be no more restrictions on daily life by the time of the next Conservative conference in 2021.

“I don’t know about you, but I have had more than enough of this disease that attacks not only human beings but so many of the greatest things about our country – our pubs, our clubs, our football, our theatre and all the gossipy gregariousness and love of human contact that drives the creativity of our economy,” he said.

Labour’s deputy leader, Angela Rayner, said: “The British people needed to hear the prime minister set out how he and his government will get a grip of the crisis. Instead we got the usual bluster and no plan for the months ahead.

“We end this Conservative conference as we started it: with a shambolic testing system, millions of jobs at risk and an incompetent government that has lost control of this virus and is holding Britain back.”

Green and pleasant land V.2

For Boris Johnson to deliver on his Green promise to power all UK homes via offshore wind by 2030, the UK government . . .

. . . will need to spend £50bn

Jillian Ambrose and Fiona Harvey report for the Guardian on the future costs of Boris Johnson's pledge on his wind generated energy target (Tue 6 Oct 2020). They write under the subheading:

Aurora Energy Research calculates investment would have to quadruple capacity

Boris Johnson’s bold new vision for offshore wind to power every home in the UK by 2030 would require almost £50bn in investment and the equivalent of one turbine to be installed every weekday for the whole of the next decade.

The huge investment, calculated by Aurora Energy Research, an Oxford-based consultancy, would increase the UK’s offshore wind power capacity by four times what it is today, to reach 40GW by 2030.

The wind energy industry has become one of the country’s most prized industrial success stories. In the past 10 years the capacity of the UK’s offshore turbines has grown from 1GW to almost 10GW at the start of 2020, and building costs have been driven down by almost two-thirds.

The government’s new plan has emerged as central to Britain’s aim to “build back better” after the coronavirus crisis towards its 2050 climate goals. But the prime minister’s green agenda will still need to clear multiple hurdles to prove that the promise of billions in investment and much-needed green jobs can be delivered.

Keith Anderson, the chief executive of Scottish Power, one of the largest investors in Britain’s renewable energy industry, said there is “no shortage of capital or investor appetite in offshore wind” but the pace and scale of the industry’s growth will depend on the government’s ability to grant new seabed licences and project contracts at record speed.

The government plans to attract investment from the private sector through a major contract auction next spring, which will also include support for onshore wind and solar power projects for the first time in four years. This upcoming auction alone could secure more than £20bn of investment and create 12,000 jobs, mainly in the construction sector, according to RenewableUK.

“I am absolutely confident that the industry can achieve this,” said Anderson. “My only nervousness is that people will start to see the 40GW as a cap. We should achieve that, and power past it. We are going to need far more clean electricity.”

The government is under pressure to produce a programme of measures that will show the UK is taking its net-zero target seriously, as host nation of the crunch UN climate talks, Cop26, which have been postponed by a year because of Covid-19.

So far, the only sizeable green measure in the chancellor’s rescue plan has been a £3bn scheme for home insulation. Even with the push to offshore wind, that still leaves a lot to be done to reach net zero.

Lady Brown of Cambridge, deputy chair of the Committee on Climate Change, said: “If we’re to reach net zero UK emissions by 2050, we’ll need to see similarly bold commitments to cut emissions from our buildings, industry, transport and land.”

There are also doubts about whether the green jobs the government says will accompany the offshore wind expansion will materialise. At least 60% of the “content” of offshore wind farms will be made in the UK, the government has promised.

Sue Ferns, from the trade union Prospect, said the prime minister’s desire to kickstart a green jobs revolution has been set out before, but “the reality has never quite matched up”.

“There is a long way to go,” she said. “The number of green jobs is still below 2014 levels despite repeated promises from the government, partly due to particular supply chain jobs being created overseas. If the prime minister’s plan for wind is to have anywhere near the promised impact on jobs then it needs a credible plan for a functional UK supply chain.”

The government’s £160m investment in upgrading the UK’s ports to manage the size of a new generation of mega-turbines will help to create supply chain hubs in port communities which face economic decline.

Nick Molho, executive director of the Aldersgate Group, said the “much-needed commitment to invest in port infrastructure” should be matched by “a clear focus on low-carbon skills” to help to grow domestic supply chains and create jobs in the sector.

But Britain will need to move fast to catch up after the head start clinched by its European neighbours, according to Dennis Clark, a 40-year North Sea oil and gas veteran who chaired Offshore Group Newcastle, a supplier to oil platforms.

Clark said the companies building offshore wind farms currently in the UK were sourcing the high-value end of their supply chain from their own countries, including Spain and Norway, and from low-cost countries such as Dubai, where working conditions and standards were lower

“We have missed out on tens of thousands of jobs, which have gone overseas,” he said. “Brexit gives us the opportunity to change that.”

History matters . . .

This painting, titled The Boyhood of Raleigh by John Everett Millais, and first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1871, is referenced throughout the Re:LODE project, as it encapsulates what it came to epitomise in the culture of heroic imperialism in late Victorian Britain, and in British popular culture up to the mid-twentieth century.

The painting depicts the young, wide-eyed Walter Raleigh and his brother sitting by the beach and sea wall at Budleigh Salterton on the Devonshire coast. He is listening to a story of life on the seas, told by an experienced sailor who points out to the sea.

Q. To what object does this index finger point?

A. Black history matters!

This indexical sign, this indexicality, points to English history too, with exactly the same exceptionalist tonality as Boris Johnson continues to use, one hundred and forty nine years later, when he made historical asides in his virtual conference speech.

Dan Bloom of The Daily Mirror reports (Tue 6 Oct 2020):

Boris Johnson awkwardly attacks Boris Johnson's past comments in conference speech

Boris Johnson has launched a somewhat surprising attack on Boris Johnson for "forgetting the history of the UK".

The Prime Minister, who has written books on Churchill and Shakespeare, slammed the Prime Minister for pooh-poohing wind farms.

He will declare in today's Tory conference speech: "I remember how some people used to sneer at wind power, twenty years ago, and say that it wouldn’t pull the skin off a rice pudding.

"They forgot the history of this country. It was offshore wind that puffed the sails of Drake and Raleigh and Nelson, and propelled this country to commercial greatness."

Fortunately, the PM doesn't need to cast his eye back 20 years to find someone "sneering" at wind power.

Only seven years ago, he himself told LBC Radio: " Labour put in a load of wind farms that failed to pull the skin off a rice pudding. We now have the opportunity to get shale gas - let's look at it."

Shale gas is better known as fracking and is furiously opposed by environmental campaigners, who say it is damaging and polluting.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak was unable to explain the contradiction when he was challenged on the PM's 2013 comments on LBC Radio.

He said: "I don’t know about then. The difference now is wind power, we know it’s clean, but it’s also now cheap and affordable, and it’s something we're very good at in this country. We can be a global leader in it. It can be a brand new industry for us, create lots of jobs."

Forgetting English history?

The wind that puffed the sails of Drake and Raleigh, puffed the sails of Drake's second cousin too, the pioneering English naval commander and administrator, privateer and an early promoter of English involvement in the Atlantic slave trade, John Hawkins.

Sir John Hawkins is considered to be the first English trader to profit from the Triangle Trade, based on selling supplies to colonies ill-supplied by their home countries, and their demand for African slaves in the Spanish colonies of Santo Domingo and Venezuela in the late 16th century.

His first voyage of 1562-63 followed Hawkins receiving a commission from Queen Elizabeth I which allowed him to privateer. England was not at war with Spain, but the commission allowed Hawkins to plunder the Spanish fleet for loot.

Hawkins formed a syndicate of wealthy merchants to invest in trade. In 1562, he set sail with three ships to Sierra Leone where he captured 300 slaves, and took them to the plantations in the Americas where he traded the slaves for pearls, hides, and sugar.

The trade was so prosperous that on his return to England the Crown supported additional voyages and granted Hawkins a coat of arms.

Detail of The Slave Trade by Auguste François Biard, 1840

By the 1690s, the English were shipping the most slaves from West Africa. Following The Acts of Union 1707, with Scotland becoming part of a British state, the Atlantic slave trade and the Triangular Trade system became a foundation of a British economy.

The first side of the triangle was the export of goods from Europe to Africa. A number of African kings and merchants took part in the trading of enslaved people from 1440 to about 1833. For each captive, the African rulers would receive a variety of goods from Europe. These included guns, ammunition, alcohol, Indigo dyed Indian textiles, and other factory-made goods. The second leg of the triangle exported enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas and the Caribbean Islands. The third and final part of the triangle was the return of goods to Europe from the Americas. The goods were the products of slave-labour plantations and included cotton, sugar, tobacco, molasses and rum.

The British maintained this position during the 18th century, becoming the biggest shippers of slaves across the Atlantic. It is estimated that more than half of the entire slave trade took place during the 18th century, with the British, Portuguese and French being the main carriers of nine out of ten slaves abducted in Africa. At the time, slave trading was regarded as crucial to Europe's maritime economy, as noted by one English slave trader: "What a glorious and advantageous trade this is ... It is the hinge on which all the trade of this globe moves."

The financial agreements and transactions that took place in Lloyds Coffee House in London to mitigate risks, both maritime and commercial, and were important for individual voyages, led to the insurance and reinsurance market and the founding of Lloyds of London. Investors mitigated risk by buying small shares of many ships at the same time. In that way, they were able to diversify a large part of the risk away. Between voyages, ship shares could be freely sold and bought.

By far the most financially profitable West Indian colonies in 1800 belonged to the United Kingdom. After entering the sugar colony business late, British naval supremacy and control over key islands such as Jamaica, Trinidad, the Leeward Islands and Barbados and the territory of British Guiana gave it an important edge over all competitors; while many British did not make gains, a handful of individuals made small fortunes.

This advantage was reinforced when France lost its most important colony, St. Domingue, to a slave revolt and the Haitian Revolution in 1791, and then supported revolts against its rival Britain, in the name of liberty after the 1793 French revolution. Before 1791, British sugar had to be protected to compete against cheaper French sugar.

After 1791, the British islands produced the most sugar, and the British people quickly became the largest consumers. West Indian sugar became ubiquitous as an additive to Indian tea. It has been estimated that the profits of the slave trade and of West Indian plantations created up to one-in-twenty of every pound circulating in the British economy at the time of the Industrial Revolution in the latter half of the 18th century.

Black history is British history

Less than a week into Black History Month in the United Kingdom Boris Johnson is either forgetting his English history, or, his version of English history is incomplete. Or, it is the continued peddling of an ideological construction, originally formulated in the nineteenth century, a fake history to validate British colonialist triumphalism, and providing grist to Johnson's political, and possibly satanic, mill.

A good reason for Re:LODE Radio to reference the Millais painting The Boyhood of Raleigh, is to "point" to some of the origins of this constructed history, a tip of an iceberg though it may be, in a present era where echoes of "Empire" have merged with a fake version of national identity, and a mass fake memory syndrome, driven by a constructed "pattern of feeling" through the worst kind of nostalgia.

The painting was influenced by an essay written by James Anthony Froude on England's Forgotten Worthies, which described the lives of Elizabethan seafarers. Froude's historical writing was characterised by its dramatic rather than scientific treatment of history, somewhat akin to the bluster some associate with the faux history Boris Johnson peddles in today's Brexit inspired culture wars.

Later in life, James Anthony Froude turned to travel, particularly through the British colonies, visiting South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and the West Indies.

From these travels, he produced two books, Oceana, or, England and Her Colonies (1886) and The English in the West Indies, or The Bow of Ulysses (1888), which mixed personal anecdotes with Froude's thoughts on the British Empire. Froude intended, with these writings, "to kindle in the public mind at home that imaginative enthusiasm for the Colonial idea of which his own heart was full.".

However, these books caused great controversy, stimulating rebuttals and the coining of the term Froudacity by Afro-Trinidadian intellectual John Jacob Thomas, who used it as the title of, Froudacity. West Indian fables by J. A. Froude explained by J. J. Thomas, his book-length critique of Froude's - The English in the West Indies. This work of 1889 was a breakthrough for Trinidad's Black intelligentsia, where Thomas countered Froude’s attack on the black population of the West Indies and thereby demolishing Froude's odious opinions. It attracted international attention and Thomas became established as an author of scholarship and ability.

According to Cedric Robinson in his study, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (1st ed., London: Zed Books, 1983. 2nd ed., Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), Thomas had a discernible impact on the evolution of Trinidad's Black intelligentsia. His work made possible the approaches to Trinidadian radical traditions that was crystallized in the lives of figures like C.L.R. James, Claudia Jones, and Eric Williams, among others.

Millais's painting was also probably influenced by a contemporaneous biography of Raleigh, which imagined his experiences listening to old sailors as a boy. Millais travelled to Budleigh Salterton to paint the location.

Millais's sons Everett and George modelled for the boys. The sailor was a professional model. Millais' friend and biographer, the critic Marion Spielmann, stated that he was intended to be Genoese. He also argues that the sailor is pointing south towards the "Spanish main".

The possible Genoese connection points to the history that must be told of how maritime exploration and so-called "discovery" was realised on one hand by Genoese mariners, and on the other by Genoese bankers who financed the Spanish wars, the Reconquista, and the Conquistador led colonial conquests. This is the beginning of capitalist expansion on a global scale.

On the eve of Black History Month (Wed 30 Sep 2020) the Guardian published this Exclusive:

Labour leader marks Black History Month with call for diverse school curriculum

The story appears in the Guardian print edition on the first day of Black History Month, Thursday 1 Oct 2020.

Heather Stewart, Political editor for the Guardian, reports:

The Labour leader, Keir Starmer, is to call for schoolchildren to be taught more about Britain’s black history, to help them reach “a full understanding of the struggle for equality”.

As he marks the start of Black History Month by visiting the Museum of London with the shadow equalities minister, Marsha de Cordova, Starmer will join calls for the curriculum to be made more diverse.

“This month we celebrate the huge achievements of Black Britons and the Black community. But Black British history should be taught all year round, as part of a truly diverse school curriculum that includes and inspires all young people and aids a full understanding of the struggle for equality,” he said, in pre-released remarks.

“While some schools are already doing this, the government should ensure all students benefit from a diverse curriculum.”

Research by the education charity Teach First found that pupils could complete their GCSEs and leave secondary school without having studied a single literary work by a non-white author.

The debate over whether the curriculum sufficiently reflects the role of BAME Britons and the diverse nature of society has been raging for many years.

The Macpherson report into the murder of Stephen Lawrence, published in 1999, asked that “consideration be given to amendment of the national curriculum aimed at valuing cultural diversity and preventing racism, in order better to reflect the needs of a diverse society”.

More than 20 years on, the Windrush “lessons learned” review suggested, “the Windrush scandal was in part able to happen because of the public’s and officials’ poor understanding of Britain’s colonial history, the history of inward and outward migration, and the history of black Britons”.

Marsha de Cordova

De Cordova said: “The Black Lives Matter movement shone a light on racism in the UK and around the world. One way for the government to act would be to ensure that young people learn about Black British history, colonialism and understand Britain’s role in the transatlantic slave trade. Black history is British history.”

Starmer called on Boris Johnson to do more to tackle racial inequalities at Wednesday’s prime minister’s questions.He highlighted in particular the fact that black mothers are five times more likely to die in pregnancy and childbirth than their white counterparts. He called the statistic “truly shocking” and urged the prime minister to launch an inquiry.Johnson replied: “This government has launched an urgent investigation into inequalities across the whole of society, and we will certainly address them in a thoroughgoing way, and I am amazed that he seems ignorant of that fact.”The prime minister was referring to the recent launch of his commission on race and ethnic disparities.Starmer’s spokesman later described that response as “disappointing and dismissive”, adding: “We do hope he will take this issue seriously.”Starmer has faced calls from some on the left of his party to take a more vocal stance on BAME issues since the death of George Floyd at the hands of US police gave fresh impetus to the Black Lives Matter movement.He was photographed with his deputy, Angela Rayner, taking a knee in solidarity with campaigners but made clear he didn’t agree with some of the actions taken in the campaign’s name – including toppling the statue of slaveowner Edward Colston in Bristol.He said at the time: “Stepping back, that statue should have been taken down a long, long time ago. We can’t, in 21st-century Britain, have a slaver on a statue.”

But he insisted: “It shouldn’t have been done in that way, completely wrong to pull a statue down like that. That statue should have been brought down properly, with consent, and put, I would say, in a museum.”He also expressed regret for referring to Black Lives Matter as a “moment”, which critics had said meant he thought it was a passing phase instead of a sustained movement.Labour has been treading carefully on “culture war” issues, which Downing Street hopes will help Johnson to draw a dividing line with Starmer’s party and help the Tories hold on to “red wall” seats.

Forgotten histories . . .

This plaque is to be found along the LODE Zone Line between Liverpool and Hull, on the outskirts of Rochdale. It was created by BBC History and is one of twenty placed around the world for the series Black and British: A Forgotten History.

This plaque commemorates the Rochdale millworkers who supported the struggle against slavery during the American Civil war and located by the Cotton Famine Road in 2016.

The cotton industry that fuelled the mills and factories of Britain’s industrial revolution came directly from the American South – produced through the labour of nearly two million African slaves.

Slavery may have been made illegal across the British Empire in 1833, but economically Britain was dependent on it. This contradiction between British morality and Britain’s economic interests came into stark relief in 1861 with the American Civil War.

The Northern states and the Southern states went into battle over the issue of slavery. The North established a Naval blockade on the Southern cotton trade and the free flow of cotton from the Mississippi valley came to an abrupt halt.

For the previously productive workers of Britain’s cotton industry this was a social and economic disaster. Lancashire was soon in the grip of what became known as ‘the cotton famine’. By the end of 1862, a total of 485,444 were receiving some form of poverty relief. The Northern states even sent food aid.

Detail from the engraving 'The cotton famine -group of mill operatives at Manchester' from the Illustrated London News, published 22 November 1862

The British government remained officially neutral. And some in Britain even found ways to break the northern blockade on cotton. But not everyone put their own interests first. One mill town was determined to do what was right. Rochdale.

Rochdale had a long history of working class radicalism. It had been one of the hot beds of the abolitionists and the anti-slavery movement.

This plaque commemorates the Rochdale mill workers who supported the struggle against slavery during the American Civil War. It is located by a road still called today what it was known as then – "Cotton Famine Road".

The road was cut across the landscape by unemployed workers from Lancashire in a public works scheme – a response to the humanitarian crisis that was unfolding in the region.

The Confederate States had hoped that distress in the European cotton manufacturing areas (similar hardships occurred in France), together with distaste in European ruling circles for Yankee democracy would lead to European intervention to force the Union to make peace on the basis of accepting secession of the Confederacy.

After Union forces had repulsed a Confederate incursion at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation. Slavery had been abolished in the British Empire by the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 three decades earlier after a long campaign, so the Unionists believed that all the British public would now see this as an antislavery issue rather than an anti-protectionism issue and would pressure its government not to intervene in favour of the South.

Many mill owners and workers resented the blockade and continued to see the war as an issue of tariffs against free trade. Attempts were made to run the blockade by ships from Liverpool, London and New York. 71,751 bales of American cotton reached Liverpool in 1862. Confederate flags were flown in many cotton towns.On 31 December 1862, a meeting of cotton workers at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, despite their increasing hardship, resolved to support the Union in its fight against slavery. An extract from the letter they wrote in the name of the Working People of Manchester to His Excellency Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America says:... the vast progress which you have made in the short space of twenty months fills us with hope that every stain on your freedom will shortly be removed, and that the erasure of that foul blot on civilisation and Christianity – chattel slavery – during your presidency, will cause the name of Abraham Lincoln to be honoured and revered by posterity. We are certain that such a glorious consummation will cement Great Britain and the United States in close and enduring regards.— Public Meeting, Free Trade Hall, Manchester, 31 December 1862.On 19 January 1863, Abraham Lincoln sent an address thanking the cotton workers of Lancashire for their support,... I know and deeply deplore the sufferings which the working people of Manchester and in all Europe are called to endure in this crisis. It has been often and studiously represented that the attempt to overthrow this Government which was built on the foundation of human rights, and to substitute for it one which should rest exclusively on the basis of slavery, was unlikely to obtain the favour of Europe.Through the action of disloyal citizens, the working people of Europe have been subjected to a severe trial for the purpose of forcing their sanction to that attempt. Under the circumstances I cannot but regard your decisive utterances on the question as an instance of sublime Christian heroism which has not been surpassed in any age or in any country. It is indeed an energetic and re-inspiring assurance of the inherent truth and of the ultimate and universal triumph of justice, humanity and freedom.I hail this interchange of sentiments, therefore, as an augury that, whatever else may happen, whatever misfortune may befall your country or my own, the peace and friendship which now exists between the two nations will be, as it shall be my desire to make them, perpetual.— Abraham Lincoln, 19 January 1863

Black history is a global history, and a testament to international solidarity between people, regardless of race!

Tank and the Bangas & Friends - What The World Needs Now

Black and British: A Forgotten History is the four-part BBC Television documentary series, written and presented by David Olusoga and first broadcast in November 2016, that instigated the placing of the Cotton Famine Road plaque.

This BBC History series documents the history of Black people in Great Britain and its colonies, starting with those who arrived as part of the Roman occupation, and relates that history to modern Black British identity.

As part of each programme, commemorative plaques - twenty in all - honouring the people discussed, were erected. In reviewing the series for The Guardian, Chitra Ramaswamy wrote:

Olusoga excavates our shared heritage with humanity and verve. One of his main messages is that remembrance is a political act. And in a present as tumultuous as ours, facing a future as uncertain as it gets, we need to look to the past more than ever. History never seemed so prescient.