No!

Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death is a 1969 semi-autobiographic science fiction-infused anti-war novel by Kurt Vonnegut.

The story is told in a non-linear order by an unreliable narrator (he begins the novel by telling the reader, "All of this happened, more or less"). Events become clear through flashbacks and descriptions of his time travel experiences. In the first chapter, the narrator describes his writing of the book, his experiences as a University of Chicago anthropology student and a Chicago City News Bureau correspondent. He also mentions his research on the Children's Crusade and the history of Dresden.

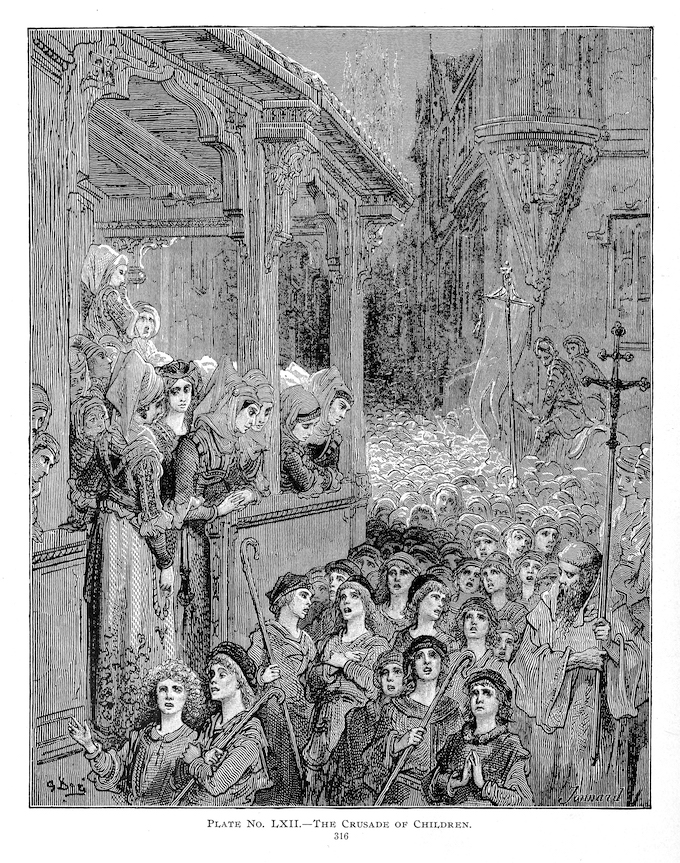

Gustave Doré illustrates this failed popular crusade by European Christians to establish a second Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem in the Holy Land, said to have taken place in 1212. The traditional narrative is likely conflated from a mix of factual and mythical events, which include the preaching of visions by a French boy and a German boy, an intention to peacefully convert Muslims in the Holy Land to Christianity, bands of children marching to Italy, and children being sold into slavery in Tunis. The crusaders of the real events on which the story is based left areas of Germany, led by Nicholas of Cologne, and Northern France, led by Stephen of Cloyes.

Dresden becomes a focal point in the novel, in both space and time and included in his visit to Cold War-era Europe with his wartime friend Bernard V. O'Hare. Dresden has a long history as the capital and royal residence for the Electors and Kings of Saxony, who for centuries furnished the city with cultural and artistic splendour, and was once by personal union the family seat of Polish monarchs. The city was known as the Jewel Box, because of its baroque and rococo city centre.

The controversial American and British bombing of Dresden in World War II towards the end of the war killed approximately 25,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and destroyed the entire city centre.

Kurt Vonnegut's plot centres on the character of Billy Pilgrim, who is captured by the German Army and survives the Allied firebombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war, an experience which Vonnegut himself lived through as an American serviceman. The work has been called an example of "unmatched moral clarity" and "one of the most enduring anti-war novels of all time".

Reversals in time/space?

This is a trailer for the 1972 film version of the novel. Vonnegut's character Billy Pilgrim is an American man from the fictional town of Ilium, New York, and believes that he was held at one time in a geodesic dome housing an alien zoo on a planet he calls Tralfamadore. There he meets Montana Wildhack, a beautiful young model who is abducted and placed alongside Billy in the zoo on Tralfamadore. She and Billy develop an intimate relationship and they have a child. She apparently remains on Tralfamadore with the child after Billy is sent back to Earth. Billy sees her in a film showing in a pornographic book store when he stops to look at the science fiction Kilgore Trout novels sitting in the window. Her unexplained disappearance is featured on the covers of magazines sold in the store. And, most importantly as a feature of the disjointed narrative Billy has experienced time travel.

There is a famous scene in Slaughterhouse Five in which Billy watches a war movie in reverse:

It was a movie about American bombers in the Second World War and the gallant men who flew them. Seen backwards by Billy, the story went like this:

American planes, full of holes and wounded men and corpses took off backwards from an airfield in England. Over France a few German fighter planes flew at them backwards, sucked bullets and shell fragments from some of the planes and crewmen. They did the same for wrecked American bombers on the ground, and those planes flew up backwards to join the formation.

The formation flew backwards over a German city that was in flames. The bombers opened their bomb bay doors, exerted a miraculous magnetism which shrunk the fires, gathered them into cylindrical steel containers, and lifted the containers into the bellies of the planes. The containers were stored neatly in racks. The Germans below had miraculous devices of their own, which were long steel tubes. They used them to suck more fragments from the crewmen and planes. But there were still a few wounded Americans, though, and some of the bombers were in bad repair. Over France, though, German fighters came up again, made everything and everybody as good as new.

When the bombers got back to their base, the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating night and day, dismantling the cylinders, separating the dangerous contents into minerals. Touchingly, it was mainly women who did this work. The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground, to hide them cleverly, so they would never hurt anybody ever again.

Using the Situationist technique of détournement a method in the SI's own words, that involves:

"[t]he integration of present or past artistic productions into a superior construction of a milieu. In this sense there can be no situationist painting or music, but only a situationist use of those means. In a more elementary sense, détournement within the old cultural spheres is a method of propaganda, a method which reveals the wearing out and loss of importance of those spheres."

Re:LODE Radio applies this technique to a general and false assumption in popular culture and politics that we have all the time in the world.

We do NOT!

The visual sequence in this video uses edited clips from the film Koyaanisqatsi, also known as Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out of Balance, that run backwards in time and just like in Billy's war film are seen in reverse.

This 1982 American experimental non-narrative film directed and produced by Godfrey Reggio with music composed by Philip Glass and cinematography by Ron Fricke consists primarily of slow motion and time-lapse footage of cities and many natural landscapes across the United States. The visual tone poem contains neither dialogue nor a vocalised narration: its tone is set by the juxtaposition of images and music. Reggio explained the lack of dialogue by stating "it's not for lack of love of the language that these films have no words. It's because, from my point of view, our language is in a state of vast humiliation. It no longer describes the world in which we live." In the Hopi language, the word koyaanisqatsi means "life out of balance".

The chosen clips, as edited in "reverse" mode, include the "creation" of urban fabric as a reversal of "demolition" and the "destruction" of trade and transport infrastructure. This edit includes the earliest footage Reggio and Fricke chose to shoot. Filming had begun in 1975 in St. Louis, Missouri using 16 mm film (due to budget constraints, despite the preference to shoot with 35 mm film), and included footage of the demolition of the Pruitt–Igoe housing project. According to "postmodern" architectural historian Charles Jencks its destruction was "the day Modern architecture died", and considered it a direct indictment of the society-changing aspirations of the International school of architecture and an example of modernists' essentially capitalist intentions running contrary to real-world social development. Following this clip, another spectacle "in reverse" shows fossil fuelled vehicles running backwards in their thousands along Californian freeways, sucking in tons of carbon based gases and polluting particulates from the environment as they proceed.

The last sequences in this edit show a thermo-nuclear test "in reverse", that sucks all the dust and radioactive fallout into a tiny ball of bright light, and followed by a slow motion detail of an explosion that creates a multi-storey building out of dust, broken glass and rubble.

The chosen sound track is the James Bond theme song "We Have All the Time in the World" sung by Louis Armstrong. Its music was composed by John Barry, with lyrics by Hal David and is a secondary musical theme in the 1969 Bond film On Her Majesty's Secret Service, the title theme being the instrumental "On Her Majesty's Secret Service", also composed by Barry. The song title is taken from Bond's final words in both the novel and the film, spoken after the death of Tracy Bond, his wife. Armstrong was too ill to play his trumpet, so it was played by another musician. Barry chose Armstrong because he felt he could "deliver the title line with irony". The instrumental version of the theme reappears twice in the 2021 James Bond film No Time to Die, in addition to the lyrical variation being played at the beginning of the closing credits.

If only it was possible to turn back time, so as in the video edit, the myriad sources of greenhouse gases over the last 250 year period, from the outset of a European capitalist industrial revolution, would instead become the source of carbon capture.

Meanwhile, in real time, the fossil fuel industries and associated vested interests, maintain the continued extraction and burning of fossil fuels as if they had all the time in the world to destroy the habitability of the planet for all of the world's biodiversity.

Q. How do these fossil fuel vested interests continue to get away with activities that threaten the UN promise to limit the rise in global heating to 1.5 and save the planet?

A. Political interests that support the privatisation of profit and the loss of habitat worldwide?

Re:LODE Radio consistently reflects on the consequences of the globalisation of the capitalist system on the experiences of people along the LODE Zone Line. Today's post is prompted by the occasion of the launch of the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), made up of the world’s leading climate scientists, setting out the final part of its mammoth sixth assessment report on Monday.

The Guardian headline for Fiona Harvey's report (Mon 20 Mar 2023) says it all:

Act now or it's too late

This was a front page story for the printed edition of the Guardian two days ago, but the headline story in the "mosaic" of stories colliding on this dateline of Tuesday 21 March 2023 was something else.

Scientists issue 'final warning' on climate is for Re:LODE Radio a story that represents an existential challenge to the entirety of humanity and the biosphere. Meanwhile the front page of the Rupert Murdoch's UK's Sun newspaper (not read so much in Liverpool) has a very different agenda.

This story is an example of a general vested interests and populist pushback on the urgent need for a responsible government response to the UK's £27bn roadbuilding strategy that will have to be redrawn to take account of environmental commitments, as the government has admitted, and as a result of a victory by climate change campaigners who sought a judicial review back in July 2021.

The Guardian headline for Gwyn Topham's report (Wed 14 Jul 2021), runs:

UK government admits it must review £27bn roads policy to account for climate

‘Fundamental changes’ to travel patterns due to the pandemic and environmental goals prompted rethink of spending on roads

The "point" that needs to be made now is that this "review" was prompted by climate activists in the face of a government abdicating its responsibility to make necessary changes to its policy. As the Guardian report says:

The government’s transport decarbonisation plan, published on Wednesday, pledged to review the national networks national policy statement, which outlined a strategy of major spending on roads.

The plan said that the “fundamental changes” brought to travel patterns by the pandemic as well as climate commitments had prompted the decision, although the government had faced a potentially difficult legal battle after court documents showed that the transport secretary, Grant Shapps, had resisted officials’ advice to review the roads policy.

The pledge means that the Department for Transport will abandon its legal defence in one of the two cases brought by the Transport Action Network (Tan). The campaigners are likely to be awarded costs.

The Guardian report continues, quoting Chris Todd, director of Tan:

The road strategy was written in 2014, before the UK’s legal commitment to net-zero and its latest carbon budget. The plan said that “it is right that we review it in the light of these developments, and update forecasts on which it is based to reflect more recent, post-pandemic conditions, once they are known.”

Chris Todd, director of Tan, said the promised review was a step in the right direction but expressed concern that action would be more important than words: “It vindicates our two legal challenges of Grants Shapps’s previous refusals to re-examine this outdated roads policy in the past 12 months. However, it won’t necessarily deliver the change needed.

“Without a suspension of the sections linked to climate change, while the review is carried out, carbon emissions will continue to be dismissed when assessing new roads. It is also unlikely that a review will happen very quickly when urgent action is required in this area.”

A second case brought by Tan – a parallel challenge to the Roads Investment Strategy (RIS2), which funds the £27bn policy – was heard in the high court last month, and a judgment is expected in the next few weeks.

“Without a cut to RIS2 funding and soon, the roads programme will continue pulling us in the wrong direction, undermining the ambition in this plan,” Todd added. “Just talking about using our cars less is not enough to achieve change when the government is spending billions on new roads, increasing traffic and congestion and driving climate change.”

The decarbonisation plan was published on the same day that a further consultation was launched to build the controversial £8bn Lower Thames Crossing.

So much for the UK government’s legal commitment to net-zero!

Since 2021 things are getting worse.

THE CURRENT SITUATION

National Highways and the Department for Transport (DfT) are preparing another round of funding for motorways and trunk roads from 2025 – 2030. This will be set out in the third Road Investment Strategy (RIS3) and could be as much as £40bn, with a substantial chunk of this allocated to building bigger roads. This is despite motorists preferring a focus on better maintenance and less disruptive roadworks. Against this, active travel and buses, in particular, are being starved of the funding needed.

In contrast, the Welsh Government recently announced that it will curtail harmful road building. New roads will still be built, but only if they pass four tests. The Scottish Government has also published a plan to achieve a 20% reduction in car kilometres by 2030.

Transport made up 24% of all carbon emissions in the UK in 2020. Most of this was from road transport. By law the UK’s emissions must be net zero by 2050, but we have some even more challenging targets to meet before then, set out in 5-yearly carbon budgets and our commitments under the Paris Agreement. While Wales and Scotland are making strides to reduce car use, England has its foot firmly on the accelerator and increasingly looks out of touch.

Lisa Hopkinson from Transport for Quality of Life, also giving evidence to MPs, said the fact that new roads generate traffic has been known for around 100 years. Yet still this gets ignored even though it means that building new roads will make it harder for the Government to reduce emissions quickly enough. This risks contributing to more extreme weather events, impacting on the economy.

As Edmund King, AA President, said at the Transport Committee hearing “Most people accept that we largely have the roads we need to get from A to B”. This then begs the question:

Q. Why is the Government still obsessed with building so many new roads, many of which make little or no sense, economically or environmentally?

(As if we had all the time in the world!)

A. Vested interests?

From the local to the global and back to the "real time" existential challenge right NOW . . .

The IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report

On the UN IPCC webpages you will find:

CLIMATE CHANGE 2023: Synthesis Trailer

On 20 March 2023 following the launch of the IPCC Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report the Secretary-General of the United Nations, António Guterres, delivered this address.

What António Guterres says is the truth, but some other truths are clearly unsaid, and only implied, perhaps offering some clues as to how to effectively drill down into the reality of what amounts to an urgent existential crisis. How will this report be received and acted upon by fossil fuel and other capitalist free market vested interests?

For example: Is there a problem with the "by 2050" zero carbon target?

As a result of COP21 the Paris Agreement's long-term temperature goal was determined to keep the rise in mean global temperature to well below 2 °C (3.6 °F) above pre-industrial levels, and preferably limit the increase to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), recognising that this would substantially reduce the effects of climate change. The target date of 2050 arises from the aim that emissions should be reduced as soon as possible and reach net-zero by the middle of the 21st century.

However, the agreement says that to stay below 1.5 °C of global warming, emissions need to be cut by roughly 50% by 2030, representing an aggregate of each country's nationally determined contributions.

The negotiations in Paris almost failed because of a single word when the US legal team realised at the last minute that "shall" had been approved, rather than "should", meaning that developed countries would have been legally obliged to cut emissions: the French solved the problem by changing it as a "typographical error". At the conclusion of COP21, on 12 December 2015, the final wording of the Paris Agreement was adopted by consensus by the 195 UNFCCC participating member states and the European Union.

On 22 September, President Xi Jinping announced in a video address to the UN general assembly that China would aim to become “carbon neutral” before 2060 – Beijing’s first long-term target. In so doing it joins the European Union, the UK and dozens of other countries in adopting mid-century climate targets, as called for by the Paris agreement.

While China's long term target 2060 kicks the target further down the timeline this a target more likely to be met, as China leads the world in the very clean technologies that make Xi’s plans feasible, at the same time as being currently responsible for 28% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, more than the United States and the European Union combined.

The Climate Action Tracker's latest published information on recent updates since 2022 of nationally determined contributions show that only five countries have submitted stronger NDC targets. Along the LODE Zone Line only Australia, along with four others, submitted a stronger NDC target. The UK, India and Indonesia did not increase their ambition.

The trouble with targets

To quote from the Abstract of the paper Will China achieve its 2060 carbon neutral commitment from the provincial perspective? the authors Li-Li Sun, Hui-Juan Cui and Quan-Sheng Ge say:

The aggregated carbon emissions at provincial level show that China can achieve its carbon emission peak of 9.64–10.71 Gt before 2030, but it is unlikely to achieve the carbon neutrality goal before 2060 without carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS). With high CCUS development, China is expected to achieve carbon neutrality in 2054–2058, irrespective of the socio-economic scenarios. With low CCUS development, China's carbon neutrality target will be achieved only under the accelerated-improvement scenario, while it will postpone to 2061 and 2064 under the continued-improvement and the business-as-usual scenarios, respectively.

However, faith and reliance on things like the implementation of future programmes of carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS) distracts from the need to:

Act now or it's too late!

While writing this post an opinion piece on the Guardian website by Rebecca Solnit, a Guardian US columnist, was published (Fri 24 Mar 2023). Her latest book, edited with Thelma Young Lutunatabua, is Not Too Late: Changing the Climate Story from Despair to Possibility.

The piece is worth quoting in full. The headline and subheading run:

Forget geoengineering. We need to stop burning fossil fuels. Right now

Pie-in-the-sky fantasies of carbon capture and geoengineering are a way for decision-makers to delay taking real action

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, one of which dropped this week, are formidably researched and profoundly important, but they mostly reinforce what we already know: human-produced greenhouse gases are rapidly and disastrously changing the planet, and unless we rapidly taper off burning fossil fuels, a dire future awaits.

The message is far from hopeless – “Mainstreaming effective and equitable climate action will not only reduce losses and damages for nature and people, it will also provide wider benefits,” said the IPCC chair, Hoesung Lee, in the press release. “This Synthesis Report underscores the urgency of taking more ambitious action and shows that, if we act now, we can still secure a liveable sustainable future for all.”

But “act now” means taking dramatic measures to change how we do most things, especially produce energy. The people who should be treating this like the colossal emergency it is keep finding ways to delay and dilute a meaningful response. Fossil fuel is hugely profitable to some of the most powerful individuals and institutions on Earth, and they influence and even control a lot of other people.

To say that is grim, but there’s also a kind of comedy in the ways they keep trying to come up with rationales to not do the one key thing that climate organizers, policy experts, activists and scientists have long told them they must do: stop funding fossil fuels, stop their extraction, stop their burning and speed the transition away from their use.

As perhaps the most powerful person to swim against their tide, the United Nations secretary general, António Guterres, said yesterday, we must move toward “net-zero electricity generation by 2035 for all developed economies and 2040 for the rest of the world” and establish “a global phase-down of existing oil and gas production compatible with the 2050 global net-zero target”. All the other actions that help the climate – including protecting forests and wild lands, rethinking farming, food, transportation and urban design – matter, but there is no substitute or workaround for exiting the age of fossil fuel.

The IPCC tells us that “[e]very increment of global warming will intensify multiple and concurrent hazards. Deep, rapid, and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions would lead to a discernible slowdown in global warming within about two decades, and also to discernible changes in atmospheric composition within a few years.” Later in the report, the scientists declare, “Projected CO2 emissions from existing fossil fuel infrastructure without additional abatement would exceed the remaining carbon budget for 1.5C.” That translates to: what we’re already extracting and using is already too much to keep to the temperature threshold set in Paris.

As climate communicator Ketan Joshi put it on Twitter, “People who make decisions about the pace of climate action and fossil fuel reliance are not behaving like they’re pulling the lever on the next few thousand years of Earth.”

They come up with endlessly creative ways to continue extracting and using fossil fuel. One of their favorites is to make commitments that can be punted off to the future, which is why one recent climate slogan is “delay is the new denial”. Another is to pretend that they are somehow still looking for a good solution and once they find it they will be very happy to use it. A holy grail, a hail Mary pass, a magic bullet, a miracle cure – or just a distracting tennis ball that too many journalists, like golden retrievers, are happy to chase.

That was clear when Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory announced its nuclear-weapons-related fusion breakthrough last winter, which the Bulletin of the Atomic Physicists noted had “at best, a distant and tangential connection to power production”. But many news stories latched on to it as if we were waiting for some miraculous solution when the solutions already exist and just need to be scaled up. It was as if they were selling us a dream of a lifeboat eventually reaching our shipwreck when viable lifeboats are all around us.

Dr Jonathan Foley, who heads Project Drawdown, joked that “fusion is here now. Look up in the sky.” The sun gives us far more energy than we can ever possibly use, now that solar panels let us convert some of that to electricity.

Among the worst of the excuses for not doing the one thing we must do is carbon capture, which has absolutely not worked at any scale that means anything and shows no sign of so doing on a meaningful scale in the near future. But while it is dangled as a possibility, it creates a justification to keep burning fossil fuel. So does geoengineering, which along with posing many kinds of disruptions is a way to compensate for continued emissions from burning things rather than stop burning them. These centralized hi-tech solutions seem to appeal to technocrats and beneficiaries of large corporations and centralized power, who perhaps don’t like or don’t comprehend the decentralization of power coming from sun and wind.

The decision-makers here often seem like a patient who, when told by a doctor to stop doing something (smoking, say, or maybe mainlining drain cleaner), tries to bargain. All the vitamins and wheatgrass juice on Earth won’t make toxic waste into something nontoxic, and all these excuses and delays and workarounds and nonexistent solutions don’t replace what the IPCC tells us: stop burning fossil fuel.

Move fast. Step it up. Now. Which brings us back to something that climate organizers have told us for a long time and the new report brings home. We know what to do, and we have the solutions we need to do it, so the biggest problems are political. They’re banks, politicians, financiers and the fossil fuel industry itself. We don’t need any magic technology to defeat them, just massive civil society willpower set in motion.

“delay is the new denial”

Distraction from distraction by distraction?

Boris Johnson's future or the future habitability of the planet? For the UK tabloid the Daily Mail the choice is clear from its front page yesterday.

When it came to it the UK's disgraced ex PM Boris Johnson's performance at today's House of Commons privileges committee was a complete shambles.

Meanwhile in yesterdays Daily Mail the pothole crisis on Britain's roads pushes the agenda from any consideration of the global challenges the entire planet faces with global heating to the local and individual impact of potholes.

Meanwhile, the cost of living crisis for many in the richest countries, the United States, the European Union and the UK, driven by market forces in the fossil fuelled energy sector means oil companies can guarantee continued receipt of government subsidies and new licences to explore for and extract new oil and gas fields. People struggling on the bread/and energyline in the world's richest economies have little power, or capacity to challenge this situation because those living a precarious existence from week to week experience a "feverish present-mindedness".

To quote from Samuel Moyn's book review of Poverty, By America by Matthew Desmond (published by Allen Lane) in Society books (Wed 22 Mar 2023):

Sociologists, Desmond charges, have shied away from “empirical studies of power and exploitation”. Politicians and well-meaning observers have wrung their hands without facing the “uncomfortable” possibility that the poor remain so because the wealthier want it that way.

The brilliance of Poverty, By America lies in Desmond’s account of how government and social policy act in ways commensurate with his class-war thesis. Its texture is provided by effective storytelling, which illustrates that poverty has become a way of life, “a relentless piling on of problems”. Living paycheck to paycheck means a precarious existence and “feverish present-mindedness” for people near the margin of daily survival.

One cause is a labour market that forces workers to help companies achieve profits while underpaying them, simply because they can. Desmond shows that the American economy has increasingly allowed business to enjoy power to coerce people into earning less for doing more. He insists he’s not a Marxist – though he writes that raising the spectre of exploitation always makes him sound like he is. Yet Desmond’s argument foregrounds precisely the extraction of surplus value that Marxists describe. The changing nature of work opportunities in America, along with the collapse of union density in the last 50 years, mean the forces of capitalism are winning. “Capitalism is inherently about workers trying to get as much, and owners trying to give as little, as possible,” Desmond observes – and poverty endures because the first group has lost many battles against the second.

And if an American ideology that harps on personal responsibility forbids direct government payments to poor people, Desmond documents how the state offers tax breaks that systematically benefit the rich (and, he might have added, corporations too). Compared with European welfare states, the US is no less generous towards its citizens – but only if they are wealthy enough. “The biggest beneficiaries of federal aid,” Desmond writes, “are affluent families.” Even when it does not privilege the privileged so glaringly, it does so in effect: the richer you are, the likelier you are to hire an accountant and get away with paying less. As a result, “a trend toward private opulence and public squalor has come to determine not simply a handful of communities, but the whole nation”. Why? Because “we like it”.

In the global context even the very poor (per person) in countries such the United States and Russia generate a carbon footprint at a much faster rate than other primary regions. The result?

Burn Baby Burn! Because "we like it"!

This potentially hellish scenario is set out in the Guardian's Environment editor Damian Carrington's analysis of the IPCC report (Mon 20 Mar 2023):

Humanity at the climate crossroads: highway to hell or a liveable future?

Damian Carrington writes:

After a 10,000-year journey, human civilisation has reached a climate crossroads: what we do in the next few years will determine our fate for millennia.

That choice is laid bare in the landmark report published on Monday by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), assembled by the world’s foremost climate experts and approved by all the world’s governments. The next update will be around 2030 – by that time the most critical choices will have been made.

The report is clear what is at stake – everything: “There is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all.”

“The choices and actions implemented in this decade [ie by 2030] will have impacts now and for thousands of years,” it says. The climate crisis is already taking away lives and livelihoods across the world, and the report says the future effects will be even worse than was thought: “For any given future warming level, many climate-related risks are higher than [previously] assessed.”

“Continued emissions will further affect all major climate system components, and many changes will be irreversible on centennial to millennial time scales,” it says. To follow the path of least suffering – limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C – greenhouse gas emissions must peak “at the latest before 2025”, the report says, followed by “deep global reductions”. Yet in 2022, global emissions rose again to set a new record.

The 1.5C goal appears virtually out of reach, the IPCC says: “In the near-term, global warming is more likely than not to reach 1.5C even under a very low emission scenario.” A huge ramping up of work to protect people will therefore be needed. For example, “extreme sea level events” expected once a century today will strike at least once a year by 2100 in half of all monitored locations.

However, the faster emissions are cut, the better it will be for billions of people: “Adverse impacts and related losses and damages from climate change will escalate with every increment of global warming.” Every tonne of CO2 emissions prevented also reduces the risk of true catastrophe: “Abrupt and/or irreversible changes in the climate system, including changes triggered when tipping points are reached.”

The report presents the choice humanity faces in stark terms, made all the more chilling by the fact this is the compromise language agreed by all the world nations – many would go further if speaking alone. But it also presents the signposts to the path the world should and could take to secure that liveable future.

Amid the maze of detail set out in the thousands of pages of supporting documents, three of these signposts stand tallest. First is that the climate crisis is fundamentally a crisis of injustice: “The 10% of households with the highest per capita emissions contribute 34-45% of global consumption-based emissions, while the bottom 50% contribute 13-15%.” The climate emergency cannot end without addressing the inequalities of income and gender for the simple reason that “social trust” is required for “transformative change”.

The second signpost is that any new fossil fuel developments are utterly incompatible with the net zero emissions required. “Projected CO2 emissions from existing fossil fuel infrastructure without additional abatement would exceed the remaining carbon budget for 1.5C,” the report says.

Put plainly, that means the oil, gas and coal projects already in operation will blow our chance of limiting heating to 1.5C, unless some are shut down early or fitted with carbon capture technology that is yet to be proven to work at scale.

The third signpost points to the technology and finance that we need:“Feasible, effective, and low-cost options for [emissions cutting] and adaptation are already available.” Solar and wind power, energy efficiency, cuts in methane emissions and halting the destruction of forests are the key ones.

The report does not shy away from the daunting scale of the choices we need to make: “The systemic change required to achieve rapid and deep emissions reductions and transformative adaptation to climate change is unprecedented in terms of scale [and] near-term actions involve high up-front investments.”

The money is key but, the report says, “there is sufficient global capital to close the global investment gaps” if barriers to the redirection of financial flows are overcome. Furthermore, it says, the costs of climate action are clearly lower than the damages climate chaos will cause.

But there is also a gaping climate policy gap, between what is in place and what is needed: “Without a strengthening of policies, global warming of 3.2C is projected by 2100.” That is the “highway to hell”.

Three decades of IPCC warnings, mostly ignored, have brought us to the climate crossroads. As we stand there, perhaps this is the simplest way to state the choice set out by the IPCC for the world’s political and corporate leaders: what price a “sustainable and liveable future for all”?

2025 NOT 2050!

Focus on achievable carbon emission reduction targets by the mid century, 2050/2060 will lead to disaster. What is required is action right now.

To follow the path of least suffering – limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C – greenhouse gas emissions must peak “at the latest before 2025”, the report says, followed by “deep global reductions”. Yet in 2022, global emissions rose again to set a new record.

For the LODE and Re:LODE project the world landscape along the LODE Zone Line leads to multiple critical positions. As previously noted in the Climate Action Tracker's latest published information on recent updates since 2022 of nationally determined contributions show that only five countries have submitted stronger NDC targets. Australia was one of these nations, however Australian government policies are way off target for following the path of least suffering – limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C – greenhouse gas emissions must peak “at the latest before 2025”, the report says, followed by “deep global reductions”.

Adam Morton's Climate crisis opinion piece in Guardian Australia sets out the necessary policy changes for the Australian government (Tue 21 Mar 2023). The headline and subheading for this opinion piece runs:

The latest IPCC report makes it clear no new fossil fuel projects can be opened. That includes us, Australia

The politics is fraught but what we do as the world aims to limit global heating to 1.5C matters

Adam Morton writes:

There is a simple line in the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that quickly cuts through the Australian debate over the future of coal and gas.

It is based on physics and maths, and has been agreed by representatives from most of the world’s governments, who spent the past week in Switzerland thrashing out the wording of a synthesis document that brings together everything established on the subject over the past eight years.

It is this: greenhouse gas emissions from existing fossil fuel infrastructure is more than enough to push the world beyond 1.5C of global heating compared with pre-industrial times. Obviously enough, it tells us that no more fossil fuel sources can be opened if the world is serious about living up to its commitments and avoiding a significantly worsening climate crisis.

This is not a fringe position. It is a mainstream, globally agreed fact that is supported by nearly 200 countries, including Australia. But it is clearly at odds with the claims by the climate change minister, Chris Bowen, among others, that it would be “irresponsible to start placing bans on traditional energy supply like coal and gas”.

The politics is fraught as hell, but we need to acknowledge that the 1.5C goal matters – and that what Australia does matters. On a recent count, it was the third biggest fossil fuel exporter and the 14th biggest national emitter.

The 1.5C goal was agreed in the landmark 2015 Paris agreement and has been reinforced by global leaders several times since. The latest IPCC report stresses what missing it would mean.

At 1.1C of heating, the world is already experiencing more emissions-linked climate damage – worsening heatwaves, bushfires, storms and droughts – than was expected. Hitting 1.5C will escalate those extreme events. More people will die or have their lives wrecked by disasters, and species and natural systems that have existed for millennia will be lost.

From there it gets worse. Every fraction of a degree matters. As the director of Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Prof Johan Rockström, said this week with admirable understatement: “There is a growing recognition that 2C is dangerous.”

Bowen made the case as well as anyone has in an interview with Guardian Australia at the Cop27 climate talks in Egypt last year, when he argued: “If we’re not trying to keep to 1.5C then what are we here for?”

If Australian politics were not still shellshocked by the climate wars, that might be the question dominating parliamentary debate this week. Instead, negotiations continue in the background between Labor and the Greens over the safeguard mechanism, which is meant to cut industrial emissions, and what to do about new coal and gas proposals. Government forecasts suggest several major new fossil fuel mines will open in the years ahead, some of them “carbon bombs” likely to add substantial amounts to global emissions.

In the next few days it should become clearer whether the Labor and Greens can find middle ground that each can claim as a win: the government by saying it has not breached its election commitments and got its climate policy through, and the Greens by saying it has extracted concessions that will make it harder to develop fossil fuels and ensure emissions don’t increase.

The IPCC report shows that if we are serious we should turn the debate on its head. Given we can’t switch off fossil fuels overnight (and nobody is arguing we can) but must limit their use ASAP, the question should be: how much of them do we need to get where we want to be as cleanly and rapidly as possible?

On coal, a research brief by the Parliamentary Library, commissioned by the Greens, suggests existing mines could be enough to meet local demand until the country’s failing old coal plants are shut and replaced. If so, great.

On gas, the government – and others – need to stop conflating local demand with the desire for multinational companies to reap profits until well after 2050 by opening vast new fields for export. As the independent senator David Pocock said on Tuesday, the much-hyped shortfall forecast for local gas supply is a political construction: about three-quarters of what we extract is exported. That can be redrawn if there is political will.

We will need gas for longer than coal, but the amount used in manufacturing and as a back-up on the east coast electricity grid is a tiny fraction of what we already extract. Homes and businesses will need to be electrified. How about we be methodical, work out an estimate of how much gas we need and go backwards from there?

On exports, we need a more sophisticated conversation that avoids falling quickly into bad faith arguments about what is happening in China (which isn’t as clear as you might think). This should acknowledge where Australian fossil fuels are genuinely needed and on what scale, and where – after an aggressive fossil fuels sales pitch in Asia under the former Coalition government – we are locking in dirty emissions sources ahead of available clean options.

Which brings us to arguably the most important point from the IPCC synthesis report: there are clean options available. In the words of ANU professors and IPCC authors Frank Jotzo and Mark Howden, we are “up the proverbial creek – but we still have a paddle”. If available tech was quickly embraced we could at least halve global emissions by 2030 at a manageable cost.

There is hope for a faster change. Let’s act like it.

Analysis: Contradictory coal data clouds China’s CO2 emissions ‘rebound’ in 2022

Adam Morton's opinion piece has a link to Carbon Brief on what's happening in China.

It's worth quoting the section in this analysis:

China’s climate goals

The reported increases in energy consumption and CO2 emissions mean that China has fallen significantly behind on its climate targets for 2025, as set out in its 14th five-year plan.

Between 2020 and 2025 the country is targeting a 13.5% reduction in energy intensity, its energy use per unit of GDP. It is also aiming for an 18% reduction in energy sector carbon intensity, its CO2 emissions per unit of GDP.

The latest official figures show China’s GDP only grew by 3% in 2022, while energy use increased by 2.9% – including the reported coal surge – and CO2 emissions from energy were up by 2.2%.

This means carbon intensity only fell by 0.8% and energy intensity by 0.1% in 2022. These sluggish improvements come on top of 2021 numbers that included a 4% increase in CO2 emissions and a 4.6% increase in coal consumption.

As a result, China’s CO2 intensity would have to fall rapidly – by 5.1% per year for the next three years – to meet the 14th five-year plan target for 2025.

Even if coal consumption growth in 2022 turns out to be over-reported and is consequently revised down to the levels implied by power and industrial output data, carbon intensity would still need to fall by 4.5% per year over the next three years.

Chinese economists are expecting GDP growth of 6.5–7.0% this year due to the reopening boost and stimulus policies. This leaves space for emissions to grow at the same time as carbon intensity improves, as long as emissions rise more slowly than GDP.

However, GDP growth is expected to come in at closer to 4-5% per year in 2024 and 2025, meaning that CO2 emissions growth will need to nearly stop or even reverse after this year.

While this might seem challenging in light of reopening, it is not a given that China’s recovery from zero-Covid will mean an increase in emissions, beyond a jump in the demand for transport fuels.

For example, consultancy MySteel expects low to no growth in coal demand in 2023. It sees little upside for heavy industry sectors and expects increases in low-carbon energy to cover most of the growth in China’s electricity demand.

The reopening of household consumption, travel and service industries will contribute to economic recovery. Growth in consumption will boost labour-intensive sectors and take care of the political need to create jobs. This could allow the government to unwind the shift to high-emissions sectors that took place during zero-Covid.

Moreover, China’s demographic shift, with declining fertility and working-age population, also means less pressure to create jobs and less demand for new real estate.

China’s leadership says it wants to prioritise household consumption in the economic recovery. The question is whether the growth in consumption will be fast enough to meet the leadership’s hopes for GDP expansion.

The targeted rate of GDP growth was left open in the current five-year plan, which allows more flexibility, but also makes policy harder to anticipate. An even bigger question is whether the moderation of energy-intensive industries that this approach would entail is politically acceptable.

A major challenge for the consumption-led recovery is that consumer confidence in China is closely tied to the property market, as real estate represents a larger share of household wealth than in any other major economy.

Local governments, which would have to provide much of the income support and social safety net to enable an increase in spending, have also seen their finances damaged by the real-estate slowdown. Therefore, the government has been relaxing the policies aimed to rein in real-estate speculation and excessive leverage in the sector.

On the other hand, re-inflating the real-estate market would be hard, even if the government wants to do it, as falling real-estate prices disrupt consumer belief in apartments as a surefire investment. Similarly, the weak state of local government finances restricts the ability to use state-led infrastructure and industrial projects to boost growth.

It is clear that the priority for the government for this year is to revive the economy, regardless of the implications for coal use and emissions. However, a successful consumption-led recovery and continued growth in low-carbon energy deployment could still put the country on track to meet its 2025 climate targets and to peak emissions well ahead of the 2030 deadline.

Note: Bold and italic text is an emphasis applied in this post.

The Juice Media (TJM) is an Australian company that produces contemporary, human rights political and social satire. They are known for their Internet series Honest Government Ads and Juice Rap News. This Honest Government Ad "We're Fine", from September 2 2019 applies now as it did then.

Extinction Rebellion's banner drop on Westminster Bridge on the morning of November 14 2018 still says it all!

Where Extinction Rebellion has NOT gone far enough, according to Natasha Josette, is NOT recognising that "the climate crisis is the result of neoliberal capitalism, and a global system of extraction, dispossession and oppression".

Right now it's not China that needs to be made accountable, it's the fossil fuel conglomerates and their sinister lobbying tactics and disinformation strategies.

Big Oil vs the World

Big Oil vs the World tells the 40 year story of how the oil industry delayed action on climate change. This BBC three-part series features never-before-seen documents, exclusive interviews with industry players, and testimony from leading scientists, politicians and CEOs. The BBC Media Centre sets out the rationale for the series:

As the UK sees record-breaking temperatures and forest fires devastate major areas of Europe, climate change is dominating news headlines. Now, a new BBC series tells the story of how we got here, charting decades of failure to tackle climate change.

Part of the award-winning This World series, Big Oil vs the World is a fascinating look at how oil giants fuelled climate change denial, despite warnings from their own scientists of the risks carbon emissions posed to the planet.

Drawing on thousands of newly discovered documents, the series goes on to chart, in revelatory and forensic detail, how the oil industry then mounted a campaign to sow doubt about the science of climate change, the consequences of which we are living through today.

Part One: Denial

Based on a year of investigative research, part one of the series: Denial tells the story of what the fossil fuel industry knew about climate change more than four decades ago, unveiling a complex campaign of media spin and political lobbying to spread scepticism on climate change.

Speaking in the film, former US Vice-President Al Gore describes the efforts of big oil companies to delay the response to climate change as “the most serious crime of the post-world war two era”.

“I think it's the moral equivalent of a war crime… The consequences of what they've done are just almost unimaginable,” he said.

In the programme, scientists who worked for the biggest oil company in the world, Exxon, reveal the warnings they sounded in the 1970s and early 1980s about how fossil fuels would cause climate change – with potentially catastrophic effects.

Discussing Exxon’s failure to act over the years, Dr Ed Garvey, who joined Exxon’s climate science research team in 1978, says that the company was aware that continuing to burn fossil fuels would mean significant climate impacts in the future.

“it's just squandered time, and we're going to pay for it,” he states.

Former United States Senator Chuck Hagel, who in the late 1990s led the charge in the US Senate against America joining an international agreement to reduce emissions, now says that the oil industry lied and misled him. “It’s cost the country, and it cost the world,” he admits.

‘Denial’ features first-hand accounts from politicians and activists fighting for action on climate change, including former Vice President Al Gore, as well as PR executives, scientists and economists paid by the oil industry.

Part Two: Doubt

Part two, Doubt, charts how the oil industry’s campaign to block action against climate change continued into the new millennium, even as the science grew more certain.

George W. Bush’s former environment chief Christine Todd Whitman explains how industry lobbyists and Vice President Dick Cheney persuaded Bush to reverse his campaign promise to cut emissions.

“It really was a tragedy. I think if President Bush had gone forward with a cap on carbon, it would have made an enormous difference,” she states.

Speaking for the first time on camera, a disaffected former ExxonMobil geoscientist and climate change specialist, Bill Heins, reflects on the disconnect between what the company’s scientists knew, and what the CEO Lee Raymond was saying publicly about climate change.

The film also unravels the story of the Koch Brothers’ extraordinarily successful effort to block President Obama’s early efforts to pass climate change legislation, and subsequent campaign to reshape the Republican Party into one in which climate denialism became the mainstream position of the party.

A lawyer who worked for Kochs through this period speaks on camera for the first time about the campaign, as does Steve Lonegan of the Koch-funded group Americans for Prosperity – who boasts that their effort “put an end to the whole climate change argument. Since then till now, it’s been a dead issue.”

BP’s former CEO Lord Browne tells the story of how BP first broke with the rest of the oil industry in acknowledging the reality of human-caused climate change, and re-branding as ‘Beyond Petroleum’. Accused of greenwashing by both environmentalists and other oil majors, Lord Browne continues to defend his record – although acknowledges that BP’s push into renewables ultimately fell short.

“Looking backwards over the last 25 years, we really have lost a quarter century in what we should have been doing,” Browne states.

Part Three: Delay

The third and final part of the series, Delay, follows the fossil fuel industry up to the present day, and examines recent efforts to hold Big Oil legally accountable for the climate crisis.

Delving into the world of fracking, revealing how big oil companies courted the Obama administration by presenting natural gas as an environmentally-friendly alternative to oil and coal.

Obama climate official Heather Zichal now acknowledges for the first time that the administration did not realise how the natural gas boom would only worsen the climate crisis. She says, “Did it turn out we had it wrong? Absolutely.”

Former ExxonMobil engineer, Dar Lon Chang, speaks for the first time on camera alleging that as the company increased its natural gas operations, it was not sufficiently monitoring methane leaks that were contributing to climate change.

“There wasn't much appetite for management to measure methane leakage because, if they found out there was a problem, they would have to do something about it,” he states.

But the film also speaks with activist Sharon Wilson who has spent more than a decade documenting methane leaks at sites operated by ExxonMobil and other oil and gas companies. Still travelling across the US in 2022, collecting evidence of ongoing leaks, she says: “We can have a future, or we can have oil and gas, but we cannot have both.”

The Kochs did not respond to requests for an interview or statement.

ExxonMobil did not grant any interviews for the series, but told the BBC in a written statement that its ‘public statements about climate change are, and have always been, truthful, fact-based, transparent and consistent with the contemporary understanding of mainstream climate science.’

ExxonMobil said it’s been an industry leader in the effort to reduce methane emissions and has been using advanced technology to detect leaks.

The company says the litigation is ‘baseless’ and ‘without merit’; and ‘there is no truth to the suggestion that ExxonMobil ever misled the public or policymakers about climate change.’

But don't you believe them!

_-_Kurt_Vonnegut.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment