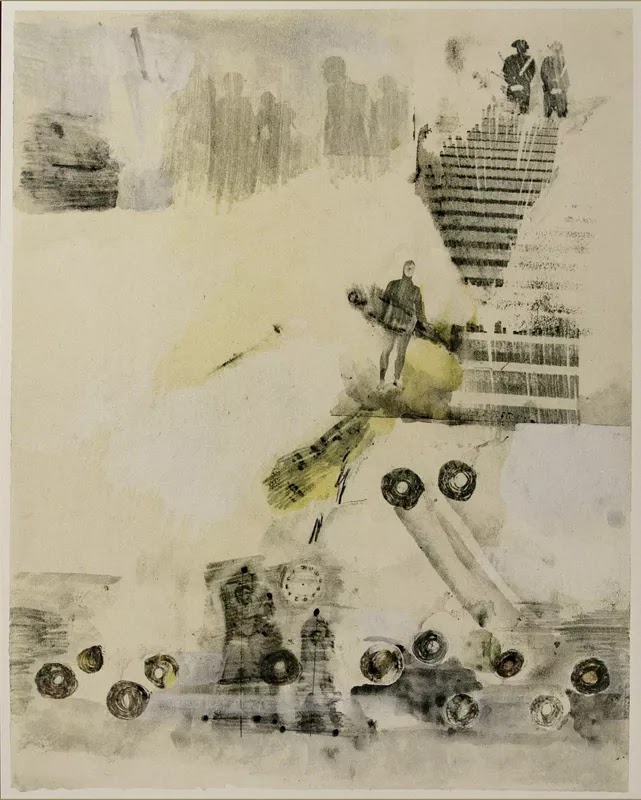

Canto XXVIII: Circle Eight, Bolgia 9, The Sowers of Discord:

The Sowers of Religious and Political Discord Between Kinsmen, from the series of Thirty-Four Illustrations for Dante’s Inferno by Robert Rauschenberg (1959-60).

Just Stop Oil pissing off rich people

DeSmog have a guide to the occupants of 55 Tufton Street and neighbouring proprties in Westminster, London, located just outside of the Westminster Abbey precinct. It was built by Sir Richard Tufton during the 17th century. Today it hosts a number of right-leaning lobby groups and thinktanks. As a result, the street name is most often used as a metonym for these groups.

As one of many targets for Just Stop Oil performative direct actions Tufton Street represents a lobbying network that is both sinister and extreme when it comes economic policy and climate crisis denial. Tufton Street is not so much about "rich people" as it is a centre for disinformation funded to defend the interests of global super-capital in the United States mobilising right-wing and anti-democratic ideological ordure.

Martin Rowson of the Guardian on the IPCC’s bleak report on the planet’s future – cartoon

The Westminster building located at 55 Tufton Street is home to a small but influential network of libertarian, pro-Brexit thinktanks and lobby groups, including the UK‘s principal climate science denial group, the Global Warming Policy Foundation. The building itself is owned by Richard Smith, a businessman whose company HR Smith Group supplies electronic systems to the aviation industry. Smith is also a former trustee of the pro-Brexit Politics and Economics Research Trust founded by former Vote Leave and Taxpayers’ Alliance CEO Matthew Elliott. While he keeps a low profile, Smith is perhaps best known for flying former Prime Minister David Cameron to his home in Shobdon, Herefordshire, in 2007. Smith donated to the official Vote Leave campaign, previously located at the same Tufton Street address. Many of the groups meet monthly to discuss “strategy and tactics”, according to an openDemocracy investigation, while Brexit campaign whistleblower Shahmir Sanni has accused nine of the organisations of running a coordinated campaign for a “hard Brexit” by agreeing on a “single set of right-wing talking points.” The building is home to several groups that either spread misinformation about climate science or lobby against government action to reduce emissions.

The Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF) exists to combat what it describes as “extremely damaging and harmful policies” designed to tackle climate change and regularly publishes reports rejecting the scientific consensus on the issue. It was founded in the run-up to the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009 by former Conservative Chancellor Lord Nigel Lawson. Several of the GWPF‘s members and funders are affiliated with other groups located at 55 Tufton Street.

Civitas is an educational charity and publisher specializing in health, education, welfare, and economics. The thinktank has published reports arguing against policies to tackle climate change, including a 2013 report by current Energy Editor of the GWPF John Constable. It claimed a shift to renewable energy would mean “more people would be working for lower wages in the energy sector, energy costs would rise, the economy would stagnate, and there would be a significant decline in the standard of living.” Sir Alan Rudge, an advisor to the GWPF, and Lord Nigel Vinson, a GWPF funder, are both trustees. The group has been criticised by Transparify for its “opaque” operations.

The TaxPayers’ Alliance is a free-market pressure group and thinktank formed in 2004 by Matthew Elliott to campaign for a low tax society. It advocates the removal of various measures designed to reduce emissions, including the Climate Change Levy. In 2016 the TaxPayers’ Alliance, along with US climate science denying lobby groups the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI) and the Heritage Foundation, held a free trade event at the Conservative Party Conference. The group was, as of November 2015, a member of the Cooler Heads Coalition, a climate science denial umbrella group run by the CEI, but is no longer listed on its website. The Taxpayers’ Alliance belongs to an international coalition of anti-tax, free-market campaign groups called the World Taxpayers Associations. Other members include the Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance, Americans for Tax Reform, the Austrian Economics Center and the Canadian Taxpayers’ Federation.

The New Culture Forum is a right-wing thinktank working to change cultural debates it believes are dominated by “the left.” According to the ConservativeHome blog, Matthew Elliott serves as an advisor to the forum, while Michael Gove, former UK Environment Secretary, has spoken at its events. Its founder and Director is Peter Whittle, former UKIP leader in the London Assembly and former Culture and Communities Spokesperson (2014-2018) and Deputy Leader (2016-2017) for the party.

57 Tufton Street, the building next door to 55 Tufton street also houses several other like-minded thinktanks.

The Centre for Policy Studies is a free market thinktank, co-founded by Margaret Thatcher in 1974, five years before she was elected Prime Minister. Lord Vinson was another co-founder of the organisation and subsequently served as Director. It regularly publishes work by climate science denier and anti-renewables advocate Rupert Darwall and runs the CapX news and comment website, which has published numerous articles by GWPF members criticising clean energy. Ahead of the UK‘s adoption of the Climate Change Act in 2008, it published a report casting doubt on climate science and arguing that energy policy should be based on long-term energy security rather than emissions reduction. The group is chaired by the billionaire financier and Conservative donor, Michael Spencer, with Sir Graham Brady, Chair of the 1922 Committee of backbench Conservative MPs, acting as Deputy Chair. More recently the group has published a series of essays from Conservative politicians which called on the party to show leadership in tackling climate change and argued in favour of a carbon border tax.

Down the road at 11 Tufton Street the address is occupied by Public First, a PR firm which aims to help its clients “understand and influence public opinion through research and targeted communications campaigns”, crafting “policy ideas that Governments can realistically apply to difficult issues”, according to its website.

The company was founded by James Frayne, a Conservative political strategist who has held roles at other PR companies such as Westbourne Communications and Portland Communications, as well as having worked as Campaign Director at the Tufton-based Taxpayers’ Alliance and as Director of Policy and Strategy at the right-leaning thinktank Policy Exchange.

Natascha Engel, former Labour MP known for her strong pro-fracking stance, became a Partner at the firm in July 2019, leading the company’s “infrastructure and regulation” division.

At 2 Lord North Street, just around the corner from Tufton Street is Lord North Street, which is home to the Institute of Economic Affairs.

The Institute of Economic Affairs is a free-market think-tank and “educational charity” founded in 1955 by the late Sir Anthony Fisher and Lord Harris with the mission “to improve understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society by analysing and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems.” Trustees linked to 55 Tufton Street organisations include Lord Vinson, Neil Record, and Michael Hintze. The IEA has received significant amounts of funding from anonymous donors through DonorsTrust, as well as yearly donations from oil giant BP, as revealed by Unearthed in 2018. It has also taken donations from tobacco companies.

23 Great Smith Street houses the Adam Smith Institute, a libertarian thinktank founded in 1977 to promote free-market ideas. It has published numerous articles and reports casting doubt on climate science and downplaying the potential of alternatives to fossil fuels, calling solar power in Britain an “impossible dream.” The group has also taken donations from tobacco companies. Co-founder and Director Eamonn Butler sits on the Economic Advisory Board of the now dormant Tufton Street organisation Global Vision.

40 Great Smith Street accommodates Open Europe, a Eurosceptic thinktank that has been accused of stoking anti-EU sentiment in the UK media. In 2010, the Economist described it as a “political campaign outfit” made up of a team of young researchers who “translate and link to stories that show the EU in a bad light, in a daily press summary that has very wide circulation among political reporters.” In 2014, it published a report criticising EU renewable energy targets which it said should be dropped “immediately”, recommending that the EU should “suspend its micromanaging energy policy-prescriptions.” In February 2020, it became part of the thinktank Policy Exchange, where its team will lead a new “Britain in the World Unit.”

The Sowers of Discord?

In Dante's poem The Divine Comedy, Hell is depicted as nine concentric circles of torment located within the Earth; it is the "realm ... of those who have rejected spiritual values by yielding to bestial appetites or violence, or by perverting their human intellect to fraud or malice against their fellowmen".

This detail of a drawing by Botticelli shows one of the Bolgia, or"Evil Ditches", in the Eighth Circle of Hell, called Malebolge. This is the Ninth Bolgia, where the Sowers of Discord are hacked and mutilated for all eternity by a large demon wielding a bloody sword; their bodies are divided as, in life, their sin was to tear apart what God had intended to be united; these are the sinners who are "ready to rip up the whole fabric of society to gratify a sectional egotism". The souls must drag their ruined bodies around the ditch, their wounds healing in the course of the circuit, only to have the demon tear them apart anew.

If only?

Meanwhile . . .

. . . two Just Stop Oil protesters who scaled a bridge on the Dartford Crossing, forcing police to close it to traffic, have been sentenced to more than two and a half years each for causing a public nuisance.

Helena Horton and agencies reported for the Guardian (Fri 21 April 2023) under the headline:

Just Stop Oil protesters jailed for Dartford Crossing protest

Under the subheading "Morgan Trowland and Marcus Decker scaled bridge over River Thames, forcing police to stop traffic", she writes:

Morgan Trowland, 40, and Marcus Decker, 34, used ropes and other climbing equipment to scale the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge, which links the M25 between Essex and Kent across the River Thames, in October last year. The police closed the bridge to traffic, causing gridlock.

Trowland was sentenced to three years in prison, while Decker received two years and seven months. Spokespeople from the activist group said these were the longest sentences for peaceful climate protest in British history.

Judge Collery KC handed down the sentence, commenting that it was a strict punishment because he wanted to deter copycat actions. Both defendants were unanimously found guilty of causing a public nuisance.

Collery said: “You have to be punished for the chaos you caused and to deter others from copying you.” The judge said Trowland, who has six previous convictions relating to protests, had a “leading role”. Decker had one previous protest-related conviction.

He told the pair “[you] plainly believed you knew better than everyone else”, adding:

“In short, to hell with everyone else.

“By your actions you caused this very important road to be closed for 40 hours,” the judge said, noting that the disruption affected “many tens of thousands, some very significantly”.

Lawyers for the men told the court they did not plan to take part in any similar climate actions in future, but the judge said he saw “no signs” the defendants were “any less committed to the causes you espouse than before”.

The prosecutor Adam King said the bridge was closed from 4am on 17 October last year to 9pm the following day, with jams forming as traffic was forced to use the tunnels under the Thames instead.

Other climate activists criticised the sentence. An Extinction Rebellion spokesperson told the Guardian: “This is absolutely devastating news. These men took incredibly courageous action to raise the alarm on the greatest crisis of our time and they should be celebrated for their bravery, not thrown in prison and brushed under the carpet.

“The majority of the UK public wants what they’re asking for, urgent and far-reaching action on the climate and ecological emergency, and this news today is a slap in the face to everyone in the UK and globally who are being impacted by climate change right now.”

Speaking outside the courtroom, Stephanie Golder, a JSO spokesperson, said: “Just Stop Oil will not be deterred by these draconian sentences. Where they imprison one of us, 10 more will take their place. When they imprison 10 of us, 100 will stand to take their place.”

The activists plan more actions from Monday next week, including “slow marches” to disrupt traffic around London.

Since the Just Stop Oil campaign began on 1 April 2022, more than 2,000 people have been arrested and 138 have spent time in prison. There are currently two Just Stop Oil and five Insulate Britain activists serving time in prison for actions taken with the campaigns.

Sectional egotism?

When it comes to Hell it is unlikely we will find Morgan Trowland and Marcus Decker anywhere among the circles of Hell, let alone in the Evil Ditches of the Eighth Circle of Hell.

On the other hand it might be expected to find Judge Collery KC in the evil ditch reserved for Hypocrites in the sixth Bolgia:

"The Poets escape the pursuing Malebranche by sliding down the sloping bank of the next pit. Here they find the hypocrites listlessly walking around a narrow track for eternity, weighted down by leaden robes. The robes are brilliantly gilded on the outside and are shaped like a monk's habit – the hypocrite's "outward appearance shines brightly and passes for holiness, but under that show lies the terrible weight of his deceit", a falsity that weighs them down and makes spiritual progress impossible for them. Friar Catalano points out Caiaphas, the High Priest of Israel under Pontius Pilate, who counselled the Pharisees to crucify Jesus for the public good (John 11:49–50)."

Canto XXIII Hypocrites

This is one of a series of transfer drawings by Robert Rauschenberg that illustrates the thirty-four cantos of Dante’s Inferno. Using John Ciardi’s translation of the poem, Rauschenberg worked with Dante scholar Michael Sonnabend to develop one composition for each of the thirty-four cantos. Combining his own drawings and watercolours with images transferred with a chemical solvent from glossy magazine reproductions, Rauschenberg provided a contemporary context for Dante’s poem.

Don't look down!

Bodycam Footage of the QE2 Bridge "intervention" on 18 October 2022 by Just Stop Oil activists Morgan Trowland and Marcus Decker.

Don’t Look Up!

Don't Look Up is a 2021 American apocalyptic political satire black comedy film written, co-produced, and directed by Adam McKay from a story he co-wrote with David Sirota.

The plot centres on Kate Dibiasky, an MSU doctoral candidate, discovers a previously unknown comet. Her professor Dr. Randall Mindy confirms that it will collide with the Earth in about six months and is large enough to cause a planet-wide extinction event. NASA confirms the findings and their Planetary Defense Coordination Office head Dr. Teddy Oglethorpe accompanies Dibiasky and Mindy to present their findings to the White House.

They are met with apathy from President Janie Orlean and her son/Chief of Staff Jason. Oglethorpe urges Dibiasky and Mindy to leak the news to the media, and they do so on a morning talk show. When hosts Jack Bremmer and Brie Evantee treat the topic frivolously, Dibiasky loses her composure and publicly rants about the threat on national television.

Mindy receives public approval for his looks; conversely, Dibiasky became the subject of negative internet memes. Actual news about the comet's threat receives little public attention and the danger is denied by Orlean's NASA Director Jocelyn Calder, a top donor to Orlean with no background in astronomy.

When news of Orlean's sex scandal with her Supreme Court nominee Sheriff Conlon is exposed, she distracts from the bad publicity by finally confirming the threat and announcing a project to strike and divert the comet using nuclear weapons. The mission successfully launches, but Orlean abruptly aborts it when Peter Isherwell, the billionaire CEO of BASH Cellular and another top donor, discovers that the comet contains trillions of dollars worth of rare-earth elements.

The White House agrees to commercially exploit the comet by fragmenting and recovering it from the ocean, using technology proposed by BASH in a scheme that has not undergone peer review.

Orlean sidelines Dibiasky and Oglethorpe while hiring Mindy as the National Science Advisor. Dibiasky tries to mobilize public opposition to the scheme but gives up under threat from Orlean's administration.

Mindy becomes a prominent voice advocating for the comet's commercial opportunities and begins an affair with Evantee.

World opinion is divided among people who believe the comet is a severe threat, those who decry alarmism and believe that mining a destroyed comet will create jobs, and those who deny that the comet even exists.

When Dibiasky returns home to Illinois, her parents kick her out of the house and she begins a relationship with a young man named Yule, a shoplifter she meets at her retail job.

After Mindy's wife confronts him about his infidelity, she returns to Michigan without him. Mindy questions whether Isherwell's technology will be able to break apart the comet, angering the billionaire.

Becoming frustrated with the administration, Mindy finally snaps and rants on live television, criticizing Orlean for downplaying the impending apocalypse and questioning humanity's indifference.

Cut off from the administration, Mindy reconciles with Dibiasky as the comet becomes visible from Earth. Mindy, Dibiasky, and Oglethorpe organize a protest campaign on social media, telling people to "Just Look Up" and call on other countries to conduct comet interception operations.

At the same time, Orlean starts an anti-campaign telling people, "Don't Look Up,". Orlean cuts Russia, India, and China out of the rights for the comet-mining deal, so they prepare their own joint deflection mission, only for their spacecraft to explode.

As the comet becomes larger in the sky, Orlean's supporters start turning on her administration. The BASH's attempt at breaking the comet apart goes awry and everyone realizes that humanity is doomed.

Isherwell, Orlean, and others in their elite circle board a sleeper spaceship designed to find an Earth-like planet, inadvertently leaving Jason behind. Orlean offers Mindy two places on the ship, but he declines, choosing to spend a final evening with his friends and family.

As expected, the comet strikes off the coast of Chile, causing a worldwide disaster and triggering an extinction-level event. The shockwave strikes Mindy's house, killing everyone inside.

In a mid-credits scene, the 2,000 people who left Earth before the comet's impact land on a lush alien planet 22,740 years later, ending their cryogenic sleep.

They exit their spacecraft naked and admiring the habitable world. Orlean is suddenly killed by a bird-like predator, one of a pack that surrounds the planetary newcomers.

In a post-credits scene, back on Earth, it is revealed that Jason managed to survive the impact. He records himself, declaring himself the "last man on Earth" and saying to "like and subscribe".

So says Miranda Whelehan in a Guardian opinion piece (Wed 13 Apr 2022).

"I wanted to sound the alarm about oil exploration and the climate crisis, but Good Morning Britain just didn’t want to hear."

I hadn’t seen the 2021 satirical film Don’t Look Up when I went on Good Morning Britain on Tuesday. I was there on behalf of Just Stop Oil – a group that has been engaging in direct action by blockading oil terminals. We’re demanding that the UK government ends all new oil licences, exploration and consent in the North Sea. It’s a simple message that’s in line with science.

But the simplicity of our demands seemed to annoy my interviewer, Richard Madeley. “But you’d accept, wouldn’t you, that it’s a very complicated discussion to be had, it’s a very complicated thing,” he said. “And this ‘Just Stop Oil’ slogan is very playground-ish isn’t it? It’s very Vicky Pollard, quite childish.” I then proceeded to talk about the recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which confirmed that it is “now or never” to avoid climate catastrophe. But they didn’t seem to care.People were quick to point out the parallels with a key scene in Don’t Look Up, when Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence’s characters, both astronomers, go on a morning talkshow to inform the public about a comet that’s heading to Earth, potentially leading to an extinction-level event. The newsreaders don’t care about what they have to say: they prefer to “keep the bad news light”.Now that I’ve watched the film, I understand the references people have been making. The worst part is that these presenters and journalists think they know better than chief scientists or academics who have been studying the climate crisis for decades, and they refuse to hear otherwise. It is wilful blindness and it is going to kill us.The response to the interview on social media has been very supportive, but we need to translate that support into action. If the thousands of people on Twitter who disagree with Madeley’s approach joined the actions of Just Stop Oil, the possibilities for change would be endless. When the interview finished, I tried to speak more to Ranvir Singh and Madeley to stress how serious this is; Madeley just told me to be quiet and watched the weather presenter.My fear is that they will only understand the reality of the climate crisis when it is on the doorstep, perhaps when the floodwater is uncontrollably trickling into their homes, or when they can no longer find food in the supermarkets. Maybe then the brutal reality of losing a “livable planet” means would actually sink in. Maybe then the journalists, presenters and climate delayers would think: “Oh, maybe we should have listened, done something.” And, of course, it will be too late.Given the government’s inaction, which I believe will be judged as criminal in the near future, there are no longer any options left than to take clear direct action in the form of civil resistance. Some of my best friends are now preparing for their next action. This will be their fourth in 12 days, perhaps also leading to their fourth time sleeping in a police cell. They are between 20 and 23. They have degrees and jobs. They should be enjoying their final weeks at university and preparing to celebrate their graduation; instead, they are putting their bodies in the way to grind the distribution of oil to a halt. No matter what the government or the media say, these are good people who are terrified for their future. They are refusing to just sit by while their government pours more fuel on their dreams and lets them go up in smoke.Civil resistance is really not about protests or marches, it is about responding to a situation beyond our worst nightmares. At Cop26, the people who run things effectively confirmed that they were going to let billions of the poorest people on this planet die in order to keep business as usual going.Well, to that we say no. We will not continue as generations have before and allow our actions today to have devastating consequences on those tomorrow. It is time to break that cycle and stand up for what is right. “If governments are serious about the climate crisis, there can be no new investments in oil, gas and coal, from now – from this year.” That is a direct quote from Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency. He said that last year. Time has quite literally run out. It only takes one quick search on the internet to see what is happening. Somalia. Madagascar. Yemen. Australia. Canada. The climate crisis is destroying lives already and will continue to unless we make a commitment to stop oil now.Miranda Whelehan is a student and campaigner with the Just Stop Oil coalition

Sowers of discord?

Fleet Street's last dinosaur of climate change denial is The Daily Telegraph as critiqued in this Commentary by Bob Ward on 23 April, 2021 produced by The London School of Economics and Political Science and the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

The leader writers at The Daily Telegraph have demonstrated once again that their deeply ideological opposition to climate change policy makes them an unreliable source of information on the topic.

Many of Britain’s national newspapers now accept the causes and potential consequences of climate change, including, belatedly, most of the right-leaning titles. But there is one remaining dinosaur which, like The Spectator magazine, desperately clings to climate change denial: The Daily Telegraph.Over the past few years, the newspaper, for which I worked very briefly as a science reporter during the 1990s, has published at regular intervals inaccurate and misleading polemics about climate change in its Comment section and its leading articles.Some of these have continued the newspaper’s longstanding rejection of the scientific evidence for climate change, including an infamously daft article in 2006 which claimed that global warming stopped in 1998.More recently it has promoted ‘lukewarmer’ climate change denial, reluctantly accepting the basic physics of the greenhouse effect, but still promoting the myth that climate change will not have much of an adverse impact.These have included an error-filled leading article in June 2019 which plagiarised, from prolific ‘lukewarmer’ Dr Bjorn Lomborg, bogus figures about the economics of the UK’s plans to cut its greenhouse gas emissions.This week The Daily Telegraph published a leading article that was also critical of the UK Government’s efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions. But it was full of sloppy errors and false arguments, revealing that the newspaper’s leader writers still do not know what they are writing about.The article was prompted by the UK Government’s announcement this week that it would accept the advice of the UK Climate Change Committee and legislate a Sixth Carbon Budget that would mean our annual emissions will be cut by 78 per cent by 2035 compared with 1990.It was widely welcomed as a bold move by Boris Johnson’s Government as it seeks to lead by example ahead of the 26th session of the Conference of Parties (COP26) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, due to be held in Glasgow, Scotland, in November.But the Telegraph’s leading article chose to snipe instead. Its final paragraph states: “When ministers grandstand in order to demonstrate their green credentials they make little mention of the bills to be paid. They need to be more honest with the voters who will be asked to pay for these pledges.”I agree that the Government should be honest about the significant investments that are required to achieve the UK’s target of reducing its annual emissions to net zero by 2050. But the Telegraph’s article was not honest in addressing this issue.Detailed analysis by the independent experts at the Climate Change Committee for the Sixth Carbon Budget found that annual investments to realise net zero emissions will need to rise from about £10 billion in 2020 to about £50 billion by 2050. These are large sums, but equivalent to less than 1 per cent of the UK’s projected GDP over this period.The Committee’s calculations also show that much of this investment will be balanced by savings, mainly by avoiding the expensive import of fossil fuels. It estimated that, for instance, electrification of the UK’s road transport would save the country over £20 billion a year by 2050.The Committee’s report concludes: “By 2050, aggregate operating cost savings will be similar to the annual investment requirements for the Net Zero transition.” And these calculations do not include the huge economic benefits of avoided climate change impacts and other severe consequences of fossil fuel use, such as local air pollution. However, none of these economic benefits are mentioned in the Telegraph’s article. It is not clear whether this was the result of ignorance or dishonesty.The article included several other factual errors. It stated: “A parliamentary report says replacing gas boilers with green alternatives could cost homeowners up to £25,000.” There has been no parliamentary report that makes such a claim. There was a letter on 21 December 2020 from Philip Dunne, the Chair of the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee, to Kwasi Kwarteng, the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, which addressed the cost of heat pumps and measures to make homes more energy efficient so that they do not waste as much heat. The letter stated: “The Northern Housing Consortium told us it will cost an average privately owned household £19,300 for retrofit and £5,000 for a heat pump.” These retrofits include new radiators, insulation and underfloor heating.However, the response from Lord Callanan, the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, indicated that the costs would be much lower. His letter stated: “Some homes will inevitably require upgrades to the heat distribution system for a heat pump to operate effectively, which could cost between £500-£1,500, but most homes in the UK are technically suitable for a heat pump with no improvements to the fabric efficiency of the building. That being said, lowering heat losses by investing in energy efficiency will improve the performance of a heat pump and reduce the overall cost of heating.”Of course, this information was ignored by the writer of the Telegraph article. The newspaper has never shown much enthusiasm for measures that would improve the energy efficiency of the UK’s homes, even though it would save its readers significant sums of money from wasted heat.The article also stated: “New boilers are to be phased out within just 12 years and 600,000 heat pumps installed.” This is plain wrong. The Government set a target in November 2020, as part of the ‘The Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution’, to increase the number of heat pump installations every year to 600,000 by 2028. There are no plans to phase out gas boilers in the UK’s 29 million homes “within just 12 years”. The Climate Change Committee did point out in its advice to the Government about the Sixth Carbon Budget that its ‘Balanced Pathway’ assumes no new gas boilers will be installed after 2033, unless they can be converted to run on electricity or hydrogen.The leader writer could have avoided these mistakes by reading the article by Telegraph Environment Editor, Emma Gatten, who reported the correct information just a few pages further forward in the same edition of the newspaper.The article contained one further mistake. It stated: “Boris Johnson has agreed with his advisers that carbon dioxide should be cut by 78 per cent by 2035 compared with 1990 levels. The previous target was a 68 per cent cut by 2030.” Again, this exposes a fundamental lack of understanding. The 68 per cent reduction in annual emissions by 2030 is not “a previous target” but instead is a separate commitment made by the UK in its ‘nationally determined contribution’ to the Paris Agreement, which was announced on 12 December 2020. Unlike the Sixth Carbon Budget, it does not include the UK’s contribution to international aviation and shipping, but both targets are consistent with each other and with the goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050.All these inaccurate and misleading claims appeared in a leading article that was less than 300 words in length. It demonstrates either huge incompetence or dishonesty, and a remarkable contempt for the newspaper’s readers.

The Telegraph published this video "Driver blocked by Just Stop Oil threatened with fine for beeping horn at protesters" on Dec 14 2022.

Who are the "sectional egoists" in this video?

The Telegraph frames the video to make a series of negative points about Just Stop Oil, but the footage itself reveals a more nuanced reality. This is the Telegraph's text on YouTube:

- Police asked Just Stop Oil to do them a "favour" by ceasing to block the road of nine cancer patients on their way to hospital.

- In their latest rush hour chaos, the eco group blockaded four lanes of traffic as they marched slowly for 90 minutes along the A503 in north London on Wednesday morning.

- A transport carrier with nine cancer patients inside was stuck in the mass gridlock for at least 30 minutes, as drivers again clashed with police for refusing to arrest the group.

- It was only allowed to pass when the driver told the dozens of police officers strolling alongside and behind the group that they were running late for crucial appointments.

The Sowers of Discord in the eighth circle of Hell

Bolgia 9 by William Blake 1824-27

Inferno XXVIII, 103-42. Still in the ninth chasm of the eighth circle, Dante and Virgil are shown with Bertrand de Born on the left, now holding out his head like a lantern, and Mosca de' Lamberti, raising the stumps of his handless arms. Bertrand de Born had set Henry II of England against his son, while Mosca de' Lamberti's murder of Buondelmonte had begun the conflict between the Guelph and Ghibelline factions in Florence.

Extinction Rebellion - Sectional egoists?

At the beginning of 2023 Extinction Rebellion announced it would temporarily;

move away from disruptive tactics

Robert Booth, Social affairs correspondent for the Guardian reported (Sun 1 Jan 2023) that the climate protest group says temporary shift will;‘prioritise relationships over roadblocks’

He writes:

The climate protest group Extinction Rebellion is shifting tactics from disruptions such as smashing windows and glueing themselves to public places in 2023, it has announced.

A new year resolution to “prioritise attendance over arrest and relationships over roadblocks”, was spelled out in a 1 January statement titled “We quit”, which said “constantly evolving tactics is a necessary approach”.

The group admitted the move would be controversial. Other environmental protest groups, such as Just Stop Oil, have stepped up direct actions, notably throwing paint at art masterpieces.

New legal restrictions on protests were introduced by the government after a wave of direct actions by climate protesters closed motorways and other infrastructure. The introduction of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act in 2022 gave police greater powers to restrict protests that cause disruption. The new public order bill is due to introduce offences of “locking on” and “interference with key national infrastructure”, which can both be punishable by imprisonment. There could be new “serious disruption prevention orders” targeting protesters “determined to repeatedly inflict disruption on the public”.

Activists with XR, which launched in 2018, became known for civil disobedience, from planting trees on Parliament Square to superglueing themselves to the gates of Buckingham Palace. Some smashed windows at bank headquarters and at News UK, the publisher of the Sun and Times newspapers. But the group became disliked by more people than liked, according to polling by YouGov.

“In a time when speaking out and taking action are criminalised, building collective power, strengthening in number and thriving through bridge-building is a radical act,” the group said.

“XR is committed to including everyone in this work and leaving no one behind, because everyone has a role to play. This year, we prioritise attendance over arrest and relationships over roadblocks, as we stand together and become impossible to ignore.”

Meanwhile, dire warnings about global heating continue: 2022 was the warmest on record in the UK, the Met Office has said, and the 10 warmest years on record have all occurred since 2003. The UN secretary general, António Guterres, has warned: “We are headed for economy-destroying levels of global heating.”

XR is calling for 100,000 people to “leave the locks, glue and paint behind” and surround the Houses of Parliament on 21 April.

“What’s needed now most is to disrupt the abuse of power and imbalance, to bring about a transition to a fair society that works together to end the fossil-fuel era,” the XR statement read. “Our politicians, addicted to greed and bloated on profits, won’t do it without pressure.”

The government has said that “over recent years, guerrilla tactics used by a small minority of protesters have caused a disproportionate impact on the hard-working majority seeking to go about their everyday lives, cost millions in taxpayers’ money and put lives at risk”.

XR also called for greater collaboration between different protest groups while admitting this may be “uncomfortable or difficult”.

“The conditions for change in the UK have never been more favourable – it’s time to seize the moment,” it said. “The confluence of multiple crises presents us with a unique opportunity to mobilise and move beyond traditional divides.

“No one can do this alone, and it’s the responsibility of all of us, not just one group … As our rights are stripped away and those speaking out and most at risk are silenced, we must find common ground and unite to survive.”

Unite to survive! Can't say fairer than that!

Gustave Doré who famously illustrated Dante's Inferno depicts the "Sowers of Discord" (1866) in the eighth circle of Hell.

In his series of images titled London: A pilgrimage, Gustave Doré depicts the common occurrence of a traffic jam on Ludgate Hill (1872). These days, and for some time now, the Dartford Crossing has been an accident hotspot, causing extensive traffic disruption as in the example of a lorry crash causing delays of up to 45mins in the image below.

Frequent delays motorists have learned to accept as "normal"!

The Dartford crossing is the busiest in the United Kingdom, with an average daily use of around 160,000 vehicles. The crossing has high levels of congestion, especially at peak times - with high levels of air pollution impacting neighbouring Thurrock and Dartford.

The crossing is the busiest in the United Kingdom, with an average daily use of around 160,000 vehicles. The crossing has high levels of congestion, especially at peak times - with high levels of air pollution impacting neighbouring Thurrock and Dartford.

Pollution levels around the Dartford Crossing have been excluded from government air quality assessments because it was classed as a "rural" road, the BBC discovered (26 March 2017).

Despite carrying 50 million vehicles a year, the status meant nitrogen dioxide recordings were not reported to the EU.

Consisting of the Dartford Tunnel and QEII Bridge, the crossing - officially known as the A282 - connects the M25 north and south of the River Thames. It has now been reclassified.

In a letter obtained by the BBC, government minister Therese Coffey conceded the error.

Dr Coffey - responsible for improving air quality on behalf of the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) - said: "The A282 in Dartford does not appear in the national air quality plan for nitrogen dioxide because it was classified as rural and was, therefore, excluded from Defra's air quality modelling assessment."

She added that the Department for Transport (DfT), which is responsible for road classification, confirmed the rural status "was incorrect".

However, the DfT told the BBC it was Defra that designated the A282 as a rural road.

The error was only recognised because Dartford Borough Council noticed the stretch of road was not included in the government's National Air Quality plan.

For 15 years the council has carried out its own air quality measurements, and each year the area around the crossing has been above the EU's target for nitrogen dioxide.

It said it passed the data to Defra, but no action was taken.

Councillor Keith Kelly, the council's head of transport and infrastructure, said the revelation was "shocking" as for years key pollution data was not seeing the light of day.

He added he was "hugely concerned" about the state of people's health because, despite the crossing being labelled as an A road, the eight lane dual-carriageway was effectively a "motorway running through the middle of our town".

The road, according to Highways England, is routinely "full to capacity". It is "one of the least reliable sections of the UK's road network" and "congestion at the crossing quickly backs up to affect local roads".

Public Health England has estimated Dartford has one of the highest percentage of deaths that can be attributed to long-term exposure to particulate air pollution in Kent.

Particulates are the deadliest form of air pollution due to their ability to penetrate deep into the lungs and blood streams unfiltered.

Thurrock, at the northern end of the crossing, has the highest estimated percentage in the East of England.

Defra has now promised to include the data "in any future assessments reported to the EU".

Because the design capacity has been exceeded, the crossing is subject to major traffic congestion and disruption, particularly when parts are closed because of accidents or bad weather. Though the government was adamant that the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge should be designed to avoid closure due to high winds, the bridge has nevertheless had to close on occasions. On 12 February 2014, during the winter storms, it was closed owing to 60-mile-per-hour (97 km/h) winds, and again on the evening of 13–14 February 2014.

Extreme weather events

The high winds during the winter storms that closed the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge on the Dartford crossing in February 2014 were extreme weather events, but not necessarily the result of climate change and global heating. However, in a warming world such storms could lead to extreme weather events resulting in catastrophic consequences compared to temporarily closing the QE II bridge.

Storm Ulysses (26-27 February 1903) was probably the most severe to affect Ireland since the Night of the Big Wind, with an estimated 1000–3000 trees uprooted in Phoenix Park, Dublin. Following a stormy period between the 18–26 which saw several depressions pass close by to the west coast of Ireland. The storm's low pressure was estimated at 975 mb (28.8 inHg) (Lamb, 1991). A quote from Ulysses by James Joyce is likely based on the aftermath of this storm - "O yes, J.J. O'Molloy said eagerly. Lady Dudley was walking home through the park to see all the trees that were blown down by that cyclone last year and thought she'd buy a view of Dublin."

A recent study of this event by the University of Reading and the National Centre for Atmospheric Science using modern forecasting to analyse paper records shows both the severity of event – and how much worse consequences would be today due to climate change and global heating.

Kevin Rawlinson reports on the results of this study in the Guardian (Mon 24 Apr 2023). He writes:

It was a storm sufficiently severe to rip up thousands of trees, leave several people dead and to warrant a mention in James Joyce’s novel Ulysses – subsequently taking its name from there.

However, it is not until now that researchers have been able to say that the 1903 tempest whipped up winds of a force seen less than once a century – making Storm Ulysses one of the worst ever seen.“We knew the storm we analysed was a big one, but we didn’t know our rescued data would show that it is among the top four storms for strongest winds across England and Wales,” said Prof Ed Hawkins, a climate scientist at the University of Reading and the National Centre for Atmospheric Science.His research team has analysed paper records of the historic extreme weather event – which would have resulted in gusts in excess of 100mph in some areas – digitised them and applied modern weather forecasting methods. “This study is a great example of how rescuing old paper records can help us to better understand storms from decades gone by. Unlocking these secrets from the past could transform our understanding of extreme weather and the risks they pose to us today,” Prof Hawkins said.The consequences if it were repeated in future would be much worse than they were in 1903 due to the effects of the climate crisis, Hawkins said. He told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme: “We can translate these past events into a modern context, in our warmer world. So, for example, we know that sea levels have already risen around our coastlines, so the storms that happened in the past would today be more damaging, because the storm surge around our coasts will be higher.“Also, because we live in a warmer world, our atmosphere is warmer and more humid, and so has more moisture in it. And so the storms will rain more than they would have done in the past.“We can understand how the risks are changing through time as the world is warming from understanding these past events.”The researchers said many storms that occurred before 1950 were left unstudied because billions of pieces of data exist only on paper. For their study, they looked at Storm Ulysses which heavily damaged infrastructure and ships when it passed across Ireland and the UK between 26 and 27 February 1903. They compared that with independent weather observations, such as rainfall data, as well as photographs and contemporaneous written accounts.Hawkins said he planned to apply the method to other historical storms. “We have lots of diaries and handwritten records in the UK and Ireland, going back well into the 1800s, which cover lots of these other storms and other extreme events that we had in the past. And so reconstructing those storms in the past will also be a very valuable initiative that we’re pursuing.”

Along the LODE Zone Line in Australia, Graham Readfearn, an environment reporter for Guardian Australia, covers an alarming story about scientists concern over the world’s ocean surface temperature as it hits a record high, warning of more marine heatwaves, leading to increased risks of extreme weather events across the planet (Sat 8 Apr 2023).

A global map using data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration showing areas in orange and red where temperatures have been above the long-term average.

Graham Readfearn reports:

The temperature of the world’s ocean surface has hit an all-time high since satellite records began, leading to marine heatwaves around the globe, according to US government data.

Climate scientists said preliminary data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa) showed the average temperature at the ocean’s surface has been at 21.1C since the start of April – beating the previous high of 21C set in 2016.“The current trajectory looks like it’s headed off the charts, smashing previous records,” said Prof Matthew England, a climate scientist at the University of New South Wales.Three years of La Niña conditions across the vast tropical Pacific have helped suppress temperatures and dampened the effect of rising greenhouse gas emissions.But scientists said heat was now rising to the ocean surface, pointing to a potential El Niño pattern in the tropical Pacific later this year that can increase the risk of extreme weather conditions and further challenge global heat records.Dr Mike McPhaden, a senior research scientist at Noaa, said: “The recent ‘triple dip’ La Niña has come to an end. This prolonged period of cold was tamping down global mean surface temperatures despite the rise of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.“Now that it’s over, we are likely seeing the climate change signal coming through loud and clear.”La Niña periods – characterised by cooling in the central and eastern tropical Pacific and stronger trade winds – have a cooling influence on global temperatures. During El Niño periods, the ocean temperatures in those regions are warmer than usual and global temperatures are pushed up.According to the Noaa data, the second-hottest globally averaged ocean temperatures coincided with El Niño that ran from 2014 to 2016.

The data is driven mostly by satellite observations but also verified with measurements from ships and buoys. The data does not include the polar regions.

More than 90% of the extra heat caused by adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels and deforestation has been taken up by the ocean.A study last year said the amount of heat accumulating in the ocean was accelerating and penetrating deeper, providing fuel for extreme weather.England, a co-author of that study, said: “What we are seeing now [with the record sea surface temperatures] is the emergence of a warming signal that more clearly reveals the footprint of our increased interference with the climate system.”Measurements from the top 2km of the ocean show the rapid accumulation of heat in the upper parts of the ocean, particularly since the 1980s.Dr Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist and distinguished scholar at the US National Center for Atmospheric Research, said observations showed the heat in the tropical Pacific was extending down to more than 100 metres.He said that heat would have knock-on effects for the atmosphere above, creating more heat, adding energy to weather systems and causing marine heatwaves.Dr Alex Sen Gupta, an associate professor at the UNSW Climate Change Research Centre, said satellites showed that on the ocean surface, temperature rises had been “almost linear” since the 1980s.

“What’s been surprising is that the last three years have also been really warm, despite the fact that we’ve had La Niña conditions,” he said. “But it is now warmer still and we are getting what looks like record temperatures.”

Sen Gupta is part of an international team of scientists studying marine heatwaves – which are classified by his group as an area of the ocean where temperatures are in the top 10% ever recorded for that time of year for at least five straight days.Current observations show moderate to strong marine heatwaves in several regions, including the southern Indian Ocean, the south Atlantic, off north-west Africa, around New Zealand, off the north-east of Australia and the west of Central America.“It’s unusual to see so many quite extreme marine heatwaves all at the same time,” said Sen Gupta.While marine heatwaves can be driven by local weather conditions, studies have shown they have increased in frequency and intensity as the oceans have warmed – a trend forecast to worsen with human-caused global heating.Hotter oceans provide more energy for storms, as well as putting ice sheets at risk and pushing up global sea levels, caused by salt water expanding as it warms.Marine heatwaves can also have devastating effects on marine wildlife and cause coral bleaching on tropical reefs. Experiments have also suggested that warming oceans could radically alter the food web, promoting the growth of algae while lowering the types of species that humans eat.Prof Dietmar Dommenget, a climate scientist and modeller at Monash University, said the signal of human-caused global heating was much clearer in the oceans.“Obviously we’re in a fast-warming climate and we’re going to see new records all the time. A lot of our forecasts are predicting an El Niño.“If this happens, we’ll see new records not just in the ocean but on land. This data is already suggesting we’re seeing a record and there could be more coming later this year.”Fire and floods associated with extreme weather events caused by global heating!

Along the LODE Zone Line in Australia a repeat of bushfires, as in this one around Nowra during the so-called black summer, prompted experts to hope that a predictive picture of the fire situation and its impact on health and the economy will aid prevention strategies.

Melissa Davey, Medical editor for Guardian Australia, reported at the beginning of 2023 (Sun 1 Jan 2023) that experts predict:

More than 2,400 lives will be lost to bushfires in Australia over a decade

She writes:

In the decade to 2030, more than 2,400 lives will be lost to bushfires in Australia, with healthcare costs from smoke-related deaths tipped to reach $110m, new modelling led by Monash University suggests.

The lead health economist with the university’s Centre for Medicine Use and Safety, Associate Prof Zanfina Ademi, who headed the analysis, said it was important to get a predictive picture of the bushfire situation in Australia and its impact on health and the economy.“This will underline preventive investment strategies to mitigate the incidence and severity of future bushfires in Australia,” she said.The black summer bushfires in 2019-20 saw almost 20m hectares of land burnt and 34 lives lost directly. One analysis estimated 417 excess deaths resulted from longer-term consequences of the fires and smoke exposure.Ademi said it was unclear what the health and economic burden of bushfires in the future may be. She and her team constructed a model that simulated follow-up of the entire Australian population yearly from 2021 to 2030, capturing bushfire deaths and years of life lived. The population in the model was updated each year by considering births, deaths and net inward migration.The impact of bushfires on gross domestic product over this period totalled $17.2bn, the model predicted, while 2,418 lives would be lost to bushfires. The model made conservative predictions, as it assumed no changes to GDP over the time period given uncertainty regarding inflation in the current economic climate.The model also did not estimate the health burden of bushfire smoke due to non-physical conditions, such as mental health, nor the burden borne by community-based healthcare services, and did not capture the impact on GP consultations nor the increased dispensation of medications for respiratory conditions. The costs of devoting healthcare resources away from other conditions was also not considered.“Even based on conservative assumptions, the health and economic burden of bushfires in Australia looms large,” the paper, published in the journal Current Problems in Cardiology, concluded.“Human-induced climate change is increasing the likelihood of catastrophic wildfires. This underscores the importance of actions to mitigate bushfire risk.”Ademi said measures such as improved fuel reduction and prescribed burning practices would be crucial to reduce health and economic burdens. While individual action was important, such as reducing fuel around property, adhering to total fire bans and reconsidering living in areas likely to be affected by fire – which she said for many people was not a “choice” – these individual actions were not enough to mitigate risk.“We need urgent involvement of government to speed up implementation of green and sustainable technologies, and we need to use collective actions at our disposable for effective social change,” she said.Dr Arnagretta Hunter, a cardiologist and Human Futures Fellow at the Australian National University, said there were many opportunities to change the trajectory of increasingly severe health and environmental impacts due to fires.“It’s not a recipe for despair,” Hunter said.“We should be empowered to see the opportunities for change that will actually make our lives better, and to harness community-based collaboration to prepare for things that haven’t happened before.“The air that we breathe, the food that we eat, the water that we need, the prices that we pay, the loss of housing, the loss of community, all these things are connected and directly impact our health and wellbeing. Especially with the change of government this year we are seeing opportunities again to discuss all of this and to reinvest in health and climate change. There’s a lot of things that are changing in the landscape.“I think what has been most powerful is that we can actually say ‘climate change’ out loud now, it’s losing its political, partisan power, and we can now acknowledge the science and discuss it intelligently and robustly, engaging our community in that discussion. And that’s an extraordinarily important part of how we prepare.”

Floods

In 2022 devastation for 33 million people in Pakistan came as catastrophic levels of rainfall, caused by global heating, resulted in the inundation of vast areas of the country.

From 14 June, through to October 2022, floods in Pakistan killed 1,739 people, and caused ₨ 3.2 trillion ($14.9 billion) of damage and ₨ 3.3 trillion ($15.2 billion) of economic losses. The immediate causes of the floods were heavier than usual monsoon rains and melting glaciers that followed a severe heat wave, both of which are linked to climate change.

On 25 August, Pakistan declared a state of emergency because of the flooding. The flooding was the world's deadliest flood since the 2020 South Asian floods and described as the worst in the country's history. It was also recorded as one of the costliest natural disasters in world history.The Pakistan floods of 2022 were ‘made up to 50% worse by global heating’ according to a study by scientists published 14 September 2022 by World Weather Attribution, concluding that the climate crisis is likely to have significantly increased rainfall and made future floods more likely.This study was flagged in the Guardian by the Environment correspondent Fiona Harvey (Thu 15 Sept 2022). She writes:

The intense rainfall that has caused devastating floods across Pakistan was made worse by global heating, which has also made future floods more likely, scientists have found.Climate change could have increased the most intense rainfall over a short period in the worst affected areas by about 50%, according to a study by an international team of climate scientists.The floods were a one in 100-year event, but similar events are likely to become more frequent in future as global temperatures continue to rise, the scientists said.The scientists were not able to quantify exactly how much more likely the flooding was made by the climate crisis, because of the high degree of natural variability in the monsoon in the region. However, they said there was a 1% chance of such heavy rainfall happening each year, and an event such as this summer’s flooding would probably have been much less likely in a world without human-induced greenhouse gas emissions.Friederike Otto, senior lecturer at the Grantham Institute for climate change and the environment at Imperial College London, said that the “fingerprints” of global heating could be clearly seen in the Pakistan floods, which were in line with what climate scientists had predicted for extreme weather.“We can say with high confidence that [the rainfall] would have been less likely to occur without climate change,” she said. “The intensity of the rainfall has increased quite a bit.” Historical records had shown heavy rainfall increasing dramatically in the region since humanity had started pouring greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, the scientists found.Otto added: “Our evidence suggests that climate change played an important role in the event, although our analysis doesn’t allow us to quantify how big the role was. This is because it is a region with very different weather from one year to another, which makes it hard to see long-term changes in observed data and climate models.”

About a third of Pakistan has been affected by the flooding, with water covering more than a tenth of the country after more than three times the average rain fell in August. Nearly 1,500 people have died and 33 million people have been affected, with 1.7m homes destroyed.

For the country as a whole it was the wettest August since 1961, and for the two southern provinces of Sindh and Balochistan the wettest on record, with about seven to eight times as much rain as usual.While the increased rainfall was influenced by the changes to the climate, local factors also played a role in the flooding and its impacts. For instance, forests in the region have been cut down over many decades, and mangrove swamps removed, while human-made dams, irrigation and other changes to the watercourses have also had an impact on natural flood patterns. Poor infrastructure, such as homes flimsily built in places prone to flooding, has also meant more people suffering as a result of the floods.Ayesha Siddiqi, assistant professor at the department of geography at Cambridge University, said: “[Flooding] has hit places where local socio-ecological systems were already pretty compromised. This disaster was the result of vulnerability constructed over a number of years, and should not be seen as an outcome of one single event.”Pakistan faces a cost of at least $30bn in damages, with the loss of food crops alone coming to about $2.3bn, a particularly heavy burden at a time of rising food prices around the world. About 18,000 sq km of cropland have been ruined, including about 45% of the cotton crop, one of Pakistan’s key exports, and about 750,000 livestock have been killed.The report on the Pakistan floods came from World Weather Attribution, a grouping of scientists from around the world who try to discern the influence of human-caused climate change on extreme weather events. They analyse such events in real time to produce quick responses on whether climate change has influenced extreme weather, a process that used to take years.Previous studies have found that climate change exacerbated the heatwaves in India, Pakistan and the UK earlier this year, and floods in Brazil. WWA found last year that the heatwave in the Pacific north-west region of the US would have been “virtually impossible” without climate change.A recent analysis by the Guardian revealed the extent to which the climate crisis is “supercharging” weather events, with devastating consequences.Otto said that countries meeting this November for the Cop27 UN climate conference in Egypt should take note of the extreme weather the world has seen this year and in recent years. “The lesson is that this will become more likely, probably a lot more likely. Becoming more resilient is very important.”Good COP! Bad COP!

The UN environment programme announced on 22 NOV 2022 that COP27 in Sharm El Sheikh had ended with the promise of an historic loss and damage fund.

Good COP

In negotiations that went down to the wire over the weekend, countries reached a historic decision to establish and operationalize a loss and damage fund, particularly for nations most vulnerable to the climate crisis.

The agreement was struck early Sunday morning as leaders concluded talks at the two-week-long United Nations Climate Conference (COP27).While many details remain to be negotiated, the fund is expected to see developing countries particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of the climate crisis supported for losses arising from droughts, floods, rising seas and other disasters that are attributed to climate change.While the negotiated text recognized the need for financial support from a variety of sources, no decisions have been made on who should pay into the fund, where this money will come from and which countries will benefit. The issue has been one of the most contentious on the negotiating table.Adapting to the climate crisis — which could require everything from building sea walls to creating drought-resistant crops — could cost developing countries anywhere from US$160-US$340 billion annually by 2030. That number could swell to as much as US$565 billion by 2050 if climate change accelerates, found UN Environment Programme’s (UNEP’s) 2022 Adaptation Gap Report.“This COP has taken an important step towards justice,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres on Sunday.

Bad COP

While many praised the creation of the fund, many also worried not enough was done at COP27, held in the Egyptian resort town of Sharm El Sheikh, to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) responsible for the climate crisis.Here is a closer look at the other key takeaways from the conference and what they could mean for the future of climate negotiations.Countries failed to decisively move away from fossil fuelsCountries repeated the “phase-down-of-coal” phrase featured in last year’s agreement at COP26 in Glasgow. While the final text does promote renewables, it also highlights “low emission” energy, which critics say refers to natural gas - still a source of GHG emissions.There were continued concerns about rising emissionsThe key result of the climate COPs is the final agreement, which is deliberated by delegates from almost 200 countries. This is usually the focus of intense negotiations, and this year was no exception, with talks lasting until Sunday morning. The final agreement did mention “the urgent need for deep, rapid and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions” to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, the most ambitious goal of the Paris Agreement. Yet there were concerns that no real progress was made on raising ambition or cutting fossil fuel emissions since COP26. That was considered bad news for a rapidly warming world.The Emissions Gap Report 2022, released by UNEP just before COP27, painted a bleak picture, finding that without rapid societal transformation, there is no credible pathway to a 1.5°C future. For each fraction of a degree that temperatures rise, storms, droughts and other extreme weather events become more severe.Why Not Just Stop Oil?

When Morgan Trowland and Marcus Decker used ropes and other climbing equipment to scale the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge, which links the M25 between Essex and Kent across the River Thames, in October last year, they intended that the police close the bridge to traffic, causing gridlock.

Why?

Because without rapid societal transformation, there is no credible pathway to a 1.5°C future. For each fraction of a degree that temperatures rise, storms, droughts and other extreme weather events become more severe, according to The Emissions Gap Report 2022, released by UNEP just before COP27.

For attempting to draw society's attention to this bleak picture Trowland was sentenced to three years in prison, while Decker received two years and seven months. These were the longest sentences for peaceful climate protest in British history.

Four days of peaceful activism led by Extinction Rebellion fail to elicit pledge from the UK government to ban new oil and gas projects.

Sandra Laville of the Guardian reports (Mon 24 Apr 2023):

After four days of peaceful demonstrations, climate activists gathered in Parliament Square as a deadline for the government to act to end all new fossil fuel projects was reached.

The actions involved a wide range of groups, including Extinction Rebellion, Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, as well as the Christian climate coalition, with thousands gathering for Earth Day in London on Saturday.The former archbishop John Sentamu was refused access to the Shell headquarters in London as he tried to deliver a letter to its chief executive, Wael Sawan. Police were present as he tried to hand over his message.Lord Sentamu said it was the most arrogant experience he had ever had. “Climate change is the greatest insidious and brutal indiscriminate force of our time. The people suffering the most have done the least to cause it,” he said in a message in support of the climate protests taking place over the weekend.“That is why continuing to search for new sources of fossil fuels, despite explicit warnings against this from the International Energy Agency, is such an offence against humanity.”The series of actions culminated on Monday with people gathering outside parliament as a deadline for the government to meet the climate demands approached.XR was demanding that by 5pm ministers agree to stop new fossil fuel projects – including halting the more than 100 new oil exploration licences being offered to companies – the first set of licences offered since 2019-20.They also want to see the setting up of emergency climate assemblies as part of a citizen-led democracy to put an end to the fossil fuel generation.After the deadline passed, the XR co-founder Clare Farrell vowed the organisations involved would step up their campaigning.“The government had a week to respond to our demands and they have failed to do so,” she said. “Next we will reach out to supporter organisations to start creating a plan for stepping up our campaigns across an ecosystem of tactics that includes everyone from first-time protesters to those willing to go to prison.”An XR spokesperson said more than 200 organisations were involved in the coalition and the support would only grow. “We have to unite to survive like never before as this government pursues increasingly repressive tactics.”The naturalist and TV host Chris Packham addressed the crowds over the weekend to make a rallying call for every last person who cares about the planet to join the community of activists.He spoke just hours after two men who scaled a bridge on Dartford Crossing as part of the Just Stop oil actions were jailed for three years and two years seven months in a sentence condemned by XR as a “slap in the face” to everyone in the UK and globally who was being affected by climate change.Judge Collery KC, who handed down the sentence, said it was designed to deter copycat actions.Morgan Trowland, 40, and Marcus Decker, 34, were convicted of public nuisance for scaling the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge, which links the M25 between Essex and Kent across the River Thames, in October.Ministers had not responded to the XR demands by Monday afternoon, as demonstrators prepared to encircle parliament.

Focussed and unfocussed anger?

Gustave Doré who famously illustrated Dante's Inferno depicts the fifth circle of Hell, the swampy, stinking waters of the river Styx where the actively wrathful fight each other viciously on the surface of the slime, while the sullen (the passively wrathful) lie beneath the water, withdrawn,"into a black sulkiness which can find no joy in God or man or the universe". At the surface of the foul Stygian marsh, Dorothy L. Sayers writes, "the active hatreds rend and snarl at one another; at the bottom, the sullen hatreds lie gurgling, unable even to express themselves for the rage that chokes them".

Road rage?

Focussed anger directed toward climate crisis protesters features in a number of video clips found on print media hosting channels on YouTube.

Road rage is not an official mental disorder, however, the behaviours typically associated with road rage can be the result of a disorder known as intermittent explosive disorder.

Intermittent explosive disorder (sometimes abbreviated as IED) is a behavioural disorder characterised by explosive outbursts of anger and/or violence, often to the point of rage, that are disproportionate to the situation at hand (e.g., impulsive shouting, screaming or excessive reprimanding triggered by relatively inconsequential events). Impulsive aggression is not premeditated, and is defined by;

a disproportionate reaction to any provocation, real or perceived.

As a working definition, road rage may be described as a constellation of thoughts, emotions, and behaviours that occur in response to;

a perceived unjustified provocation while driving.

A number of nonspecific psychological factors may contribute to road rage, as well. These include;

the tendency to displace anger and attribute blame to others.

Are these clips reflective of the attitude of the consumers or the producers. Or is it just more "clickbait" monetised to sell advertising?

Hypocrite lecteur, — mon semblable, — mon frère!(Hypocrite reader! — My twin! — My brother!)This is a famous line found in Charles Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal, a modern "evil ditch" in a modern "Inferno", where the accusation of hypocrisy (Eighth circle of Hell, and Bolgia 6) is pointedly addressed to the reader: Au LecteurThe last verse of the poem runs:C'est l'Ennui! L'oeil chargé d'un pleur involontaire, II rêve d'échafauds en fumant son houka. Tu le connais, lecteur, ce monstre délicat, — Hypocrite lecteur, — mon semblable, — mon frère!And has been translated many times with different emphases. This is a translation of the last three verses by Eli Siegel."But among the jackals, the panthers, the bitch-hounds, The apes, the scorpions, the vultures, the serpents, The monsters screeching, howling, grumbling, creeping, In the infamous menagerie of our vices,There is one uglier, wickeder, more shameless! Although he makes no large gestures nor loud cries He willingly would make rubbish of the earth And with a yawn swallow the world;He is Ennui! — His eye filled with an unwished-for tear, He dreams of scaffolds while puffing at his hookah. You know him, reader, this exquisite monster, — Hypocrite reader, — my likeness, — my brother!"My consumers, are they not my producers?

Interestingly, it is evident in many of these encounters that the long suffering protesters do not come across as particularly aggressive when subjected to various forms of abuse.

Q. Pissing off the public?

A. Yes

But in this clip the heartfelt emotion being communicated is;

anguish!

When it comes to abuse, the line was crossed when the Hertfordshire police abused their powers in unlawfully arresting journalists at a Just Stop Oil protest on the M25.

Damien Gayle reported for the Guardian on the targeting of journalists by police in Hertfordshire during November 2022 (Wed 21 Dec 2022). He writes under the subheading:

Exclusive: Force says it falsely imprisoned photographer covering M25 climate action

A regional police force has admitted it unlawfully arrested and violated the human rights of a photographer who was held while covering climate protests on the M25.

Ben Cawthra was one of four journalists arrested by Hertfordshire constabulary while covering protests by Just Stop Oil last month. Supporters of the climate campaign had climbed gantries to disrupt traffic on London’s orbital motorway.A previous investigation, commissioned by the Hertfordshire force, concluded “police powers were not used appropriately” in making the arrests, but stopped short of admitting they were unlawful.Now, after Cawthra began legal action, Hertfordshire constabulary have admitted their officers acted unlawfully by arresting him and violated his right to free speech, and the force has accepted liability for false imprisonment over his detention.Cawthra’s lawyer, Jules Carey, of Bindmans, said the case represented an important clarification of the principle of freedom of the press. “It is vital to the health of a democracy that journalists can work without fear of arrest or detention by the police,” he said.“We welcome the prompt admission by the chief constable of Hertfordshire that Mr Cawthra’s arrest and detention for 16 hours was unlawful and constituted a false imprisonment, and we strongly support the recommendation that all public order officers undertake the College of Policing/National Union of Journalists’ training, which explains the rights of reporters and photographers during public order situations.”On 7 November, Cawthra, a director of the picture agency London News Pictures, who has been a photojournalist for two decades, drove to Hertfordshire after becoming aware that protests on the M25 were planned by Just Stop Oil, according to a letter before action sent to the Hertfordshire constabulary.After spotting police officers lying in wait in an unmarked car close to the town of London Colney, Cawthra parked his car and stationed himself nearby on a public footpath on a bridge overlooking the motorway.From his vantage point, he saw and began taking photographs of a man climbing a gantry. As more police began to arrive, an officer came over and asked Cawthra to stay where he was.“Mr Cawthra responded to say that he was on a public footpath, and that he had the right to leave at any point, though he said that he would comply with the officer’s request,” the letter saidThe officer then asked to see Cawthra’s press ID. However, the officer did not call the number on the card to confirm his credentials, and instead asked to see his driving licence, as Cawthra continued to photograph the protest.Minutes later, the officer returned and arrested Cawthra on suspicion of conspiracy to cause a public nuisance. He was taken to Hatfield police station and held for 16 hours.Two other journalists were arrested that day, and a third the next day. Outrage grew after Charlotte Lynch, an LBC reporter, went public about her arrest, leading to criticism from ministers and human rights organisations.

Amid the outcry, Hertfordshire constabulary asked an outside force to review the circumstances around the arrests. The investigation concluded frontline officers had been directed to arrest journalists by their seniors, without developing sufficient grounds to do so.

Cawthra and the other arrested journalists have already received a letter of apology from the Hertfordshire chief constable, Charlie Hall. But now, after the legal action, the force will pay Cawthra compensation for his unlawful detention. He has also called on the police to ensure officers complete training on the rights of journalists during public order situations.A Hertfordshire constabulary spokesperson said: “The chief constable has apologised to the journalists arrested in connection with the matter of policing M25 protests, and he had asked for a review, which was undertaken by Cambridgeshire constabulary. The recommendations made in the review regarding learning have been accepted.“Our officers acted in good faith throughout, but mistakes were made. The police do not wish to comment any further on individual cases which are under legal consideration.“The police force is committed to protecting the public and businesses in carrying out their lawful activities.”

Rich Felgate says this footage shows his and Tom Bowles's arrests on Monday (7 October) on a footbridge over the M25.