Just Stop Oil!

Two Just Stop Oil activists arrested at Dippy the Diplodocus exhibit in Coventry

Jessica Murray, Midlands correspondent for the Guardian reports (Mon 10 Apr 2023):

Two Just Stop Oil protesters have been arrested after jumping over a barrier surrounding the Dippy the Diplodocus exhibit in Coventry.

Video footage captured the campaigners, named by the environmental group as Daniel Knorr, 21, and Victoria Lindsell, 67, jumping over the fencing before being grabbed by staff at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum at around 10am on Monday.

The pair were subsequently arrested on suspicion of conspiracy to cause criminal damage, with West Midlands police adding that “two large bags of dry paint” were also seized by officers.

The force said protest liaison officers remained at the scene to “keep people safe and limit disruption to a minimum”.

Footage showed staff members in high viz jackets grabbing Knorr’s rucksack and tackling Lindsell during the protest, with one shouting: “Stop it, stop it now. Do you understand?”

The demonstrators both removed their jumpers to reveal white “Just Stop Oil” T-shirts.

As he was led away in handcuffs by police, Knorr was recorded saying: “Kids need to grow up in a world where they’re safe, not where they’re worrying about if there is enough food to eat. Not when they’re watching TV seeing millions of people die in deadly heatwaves.”

Just Stop Oil said the protest was to highlight the threat of new fossil fuels, adding: “the plaster cast is safe; we are not.” In a statement after the arrests, the group said: “Humanity is at risk of extinction, and so is everything we have ever created.

“Our works of art, our favourite novels, our historical buildings and artefacts, our traditions – we’re terrifyingly close to losing everything we value and love. We cannot rely on our criminal government or our cherished institutions to save us.”

The Dippy the Diplodocus exhibit opened in Coventry in February, with the famous dinosaur cast on loan from the Natural History Museum for three years.

West Midlands police said: “A woman, aged 67, and a man, aged 21, have been arrested on suspicion of conspiracy to cause criminal damage and remain in custody for questioning.”

Meanwhile . . .

. . . "New oilfield in the North Sea would blow the UK's carbon budget"

Fiona Harvey, the Guardian's Environment editor, reports on Saturday 1 April 2023 that:

Campaigners say Rosebank, with a potential yield of 500m barrels, would seriously undermine legal commitment to net zero

April 1st? April fools? Fake news . . .

The Guardian newspaper has been famously adept at creating "fake news" stories for April fools day, going back to their most successful April Fool’s joke, San Serriffe on 1 April 1977. On this occasion the Guardian produced a seven-page travel supplement on the tiny tropical republic of San Serriffe, “a small archipeligo, its main islands grouped roughly in the shape of a semicolon, in the Indian Ocean”, which was apparently celebrating 10 years of independence.

Last year on the 1st April 2022 the Guardian ran this story by Mari Tyme:

Tory MPs lobby No 10 to let royal family use seized Russian superyacht

Unfortunately, given the times we are living through, the Guardian coverage of the Rosebank oilfield, and its potential to undermine the UK's legal commitment to meet net zero targets, is NOT "fake news".

Fiona Harvey writes:

A single new oil and gas field in the North Sea would be enough to exceed the UK’s carbon budgets from its operations alone, analysis has shown, as the government considers fossil fuel expansion despite the legally binding commitment to net zero.

Rosebank is the biggest undeveloped oilfield in the North Sea, with the potential to produce 500m barrels of oil, and has already cleared several regulatory hurdles, meaning a decision on its future could come soon.

But analysis by the campaigning group Uplift has shown that the likely emissions just from producing oil from the field would be enough to exceed the share of the UK’s carbon budgets that should come from oil and gas production, from 2028 onwards.

That would mean other sectors of the economy would have to cut their emissions further and faster to enable the UK to stay within its carbon budgets, if the Rosebank field went ahead.

The findings raise further questions over the government’s plans to push ahead with the development of oil and gas despite pleas from scientists and the UN to halt new licences. Ministers are in the midst of a new licensing round for oil and gas in the North Sea, and this is expected to continue despite the net zero strategy. The government’s energy security and net zero strategies, running to more than 1,000 pages, were unveiled on Thursday. They contain a major gamble on carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, which will receive £20bn of government support over 20 years, and which ministers said would allow for continued fossil fuel use.

But scientists told the Observer that using CCS in this way was a dangerous gamble, and that calling off any proposed new development of oil and gas was a safer way to meet the net zero commitment.

The Rosebank field, to be developed by the Norwegian state-owned energy company Equinor, is about three times the size of the Cambo field, which was the subject of intense campaigning before being paused last year.

The emissions from Rosebank’s operations alone – not counting any emissions from burning the oil and gas it is likely to produce – are likely to reach 5.6m tonnes of carbon dioxide, according to analysis by Uplift of the environmental statements provided by Equinor.

This would be enough, when added to the emissions from the operations of existing oil and gas fields, to exceed the amount of emissions that should be allowed to come from the UK’s oil and gas sector, within the UK’s total carbon budget, from 2028.

Counting Rosebank’s likely emissions, oil and gas production would exceed its theoretical share of the UK’s fifth carbon budget, from 2028 to 2032, by about 8%, and exceed its share of the sixth carbon budget, from 2033 to 2037, by about 17%.

The carbon budget is not formally divided up among emitting sectors, but the Committee on Climate Change provides guidelines suggesting that various sectors should stay within approximate limits. By this reckoning, North Sea oil and gas operations should account for only about 4% of the UK’s carbon budgets, which run for five years each and have so far been set out to 2037.

Tessa Khan, executive director of Uplift, said: “This analysis clearly shows what the government has long known but chosen to ignore: that it is impossible to reconcile approving a huge new oilfield like Rosebank with the UK meeting its climate obligations.”

She pointed out that the development could be eligible for £3.57bn in tax breaks under the windfall tax, which hands companies incentives for investing in increased oil and gas production.

“Ministers also know that approving Rosebank will do nothing to lower UK fuel bills and will do very little for UK energy security as most of these reserves will likely be exported. On every level, including legally, Rosebank fails.”

Ed Miliband, Labour’s shadow secretary for climate and net zero, said: “After the miserable failure of ‘green day’ confirmed that the Conservatives will never meet Britain’s energy needs or create the clean jobs of the future, the idea that they are about to throw billions at new fossil fuel exploration shows that they will scandalously waste money on climate vandalism. The evidence is clear: Rosebank will do nothing to cut bills, as the government admit, is no solution to our energy security, and would drive a coach and horses through our climate commitments.”

Grant Shapps, secretary of state for energy security and net zero, said at the launch of the government’s Powering Up Britain strategy on Thursday that a decision on Rosebank was “not on my desk”.

He defended the continued licensing of oil and gas, despite a plea by 700 scientists last week for the UK to halt new development, and the urging of the UN secretary general, António Guterres, for countries to forgo fossil fuel development and reach net zero by 2040.

From bad to worse?

A spokesperson from the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero said: “We are on track to deliver our carbon budgets, creating jobs and investment across the UK while reducing emissions. Our carbon budget delivery plan is a dynamic long-term plan for a transition that will take place over the next 15 years, setting us on course to reach net zero by 2050.”

Liar, Liar - The Castaways (1965)

"Liar, Liar," by 1960s garage rock band The Castaways. Dance performance by The Honey Bees (Mary Ann, Ginger and Lovey) featured on Gilligan's Island.

From San Serriffe to Gilligan's Island

Gilligan's Island was the fictional setting for an American sitcom created and produced by Sherwood Schwartz. It aired for three seasons on the CBS network from September 26, 1964, to April 17, 1967. The series follows the comic adventures of seven castaways as they try to survive on an island where they are shipwrecked. Most episodes revolve around the dissimilar castaways' conflicts and their unsuccessful attempts to escape their plight, with Gilligan usually being responsible for the weekly failures.

From terrible to even worse?

UK insulation scheme would take 300 years to meet government targets, say critics

Jillian Ambrose Energy correspondent writes (Sun 9 Apr 2023) under this subheading:

Exclusive: National Energy Action says progress on energy efficiency is too slow and not well targeted at fuel-poor households

The government’s home insulation scheme would take 190 years to upgrade the energy efficiency of the UK’s draughty housing stock, and 300 years to meet the government’s own targets to reduce fuel poverty, according to industry calculations.

Critics of the Great British Insulation Scheme, which aims to insulate 300,000 homes a year over the next three years, have raised concerns that the plan does not go far enough to reach the 19m UK homes that need better insulation.

The Labour party added that it would fail to address the government’s “disastrous record on heating our homes”: the rate of energy efficiency upgrades is 20 times lower than under the last Labour government.

The UK Business Council for Sustainable Development has calculated that the pace of the new scheme, announced as part of a wide-ranging energy security strategy last week, would take almost 200 years to reach the homes in need of upgrades.

The scheme would take another 100 years to meet the government’s own targets for improving the home energy efficiency of households living in fuel poverty in England alone, according to fuel poverty charity National Energy Action.

“We simply don’t have that long to act,” said Jason Longhurst, chair of the UK Business Council for Sustainable Development.

Matt Copeland, head of policy at National Energy Action, said progress on energy efficiency in the UK had “been far too slow for a decade”, and that the new scheme was “not well targeted at fuel-poor households, who need the most support with their bills”.

He added: “Our own analysis from the most recent set of fuel poverty statistics for England found that it will now take approximately 300 years for the government to hit its statutory target for all fuel-poor homes to reach EPC C – far behind the 2030 deadline.”

A spokesperson for the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero said that “strong progress is being made to insulate homes” and that the government does “not recognise this analysis”.

Entr'acte

"Liar, Liar, Pants on Fire"

Home insulation grants are considered a crucial part of the UK’s plan to become a net-zero-carbon economy by 2050 by making homes more energy-efficient. They would also offer immediate benefits to households by making homes warmer and lowering energy bills. However, the pace of home energy efficiency upgrades has stalled in recent years, leaving almost two-thirds of UK homes in need of better insulation.

The number of UK energy efficiency installations, such as insulating lofts and cavity walls, peaked in 2012 at 2.3m, but under the Conservative government, efficiency programmes were slashed, leading to a slump in home upgrades. By 2021, annual installations were 96% lower, at fewer than 100,000.

Ed Miliband, the shadow secretary of state for climate change and net zero, accused the prime minister, Rishi Sunak, of failing to act despite the sharp rise in home energy bills because of rocketing market prices after the war in Ukraine.

“One of the reasons that energy bills are so high is the Conservatives’ disastrous record on heating our homes. Energy efficiency rates are now 20 times lower than under the last Labour government, but Rishi Sunak is failing to act,” he said.

The Labour party has put forward plans for a large-scale energy efficiency drive to make sure all of the UK’s 27m homes are properly insulated. If elected to government, Labour would aim to upgrade the energy efficiency of 2m households in the first year of a decade-long £60bn scheme that could save households £400 on bills annually.

The party claims that by the end of the decade, 450,000 jobs would be created by installing energy-saving measures such as loft insulation and double glazing, renewable and low carbon technologies.

“Labour’s warm homes plan would upgrade the 19m homes that need it, cutting bills and creating thousands of good jobs for electricians and engineers across the country,” Miliband said.

A government spokesperson said: “The Great British Insulation Scheme will support the installation of energy efficiency measures to around 300,000 homes. It is in addition to the £6.6bn we have committed in this parliament, and the additional £6bn of investment to 2028, to help cut emissions from homes and buildings.”

For a ha'p'orth of tar the boat sank!

Ben Jennings on Rishi Sunak and the ship of state – cartoon in the Guardian Thursday 19 January 2023

From Gilligan's Island to Thorney Island (Westminster)

Thorney Island was the eyot (or small island) on the Thames, upstream of medieval London, where Westminster Abbey and the Palace of Westminster (commonly known today as the Houses of Parliament) were built. It was formed by rivulets of the River Tyburn, which entered the Thames nearby. In Roman times, and presumably before, Thorney Island may have been part of a natural ford where Watling Street crossed the Thames, of particular importance before the construction of London Bridge.

The UK government response to something as straightforward as insulating Britains housing stock, and the "degree of spin" exercised by government spokespersons inhabiting Thorney Island, reveals that they are not interested in reality, or addressing practical solutions, and will avoid accountability for the stark inequalities in UK society at all costs. This political stance is amplified by what may be described in this post as an "island mentality", or what is commonly referred to as the "Westminster bubble".

Outside the "bubble", outside the "echo chambers" of the "anti-woke", extraordinary people have been taking a stand and protesting under the banner of:

Insulate Britain

A series of protests by the group Insulate Britain involving traffic obstruction began on 13 September 2021. The group has blockaded the M25 and other motorways in the United Kingdom, as well as roads in London and the Port of Dover.

The protesters demand that the government improve the insulation of all social housing in the UK by 2025 and retrofit all homes with improved insulation by 2030. Improved insulation of homes would likely reduce the use of fuel, such as natural gases and oil, to adjust the internal temperature, thus improving energy efficiency in British housing and mitigating climate change.

The group has drawn support from some, but condemnation from others, including from individuals within the government.

On 17 November 2021, nine protesters were imprisoned for breaching an injunction against road blockade protests. On 2 February 2022, five protesters were imprisoned for the same reason, with eleven others receiving suspended sentences.

As Insulate Britain began its protests in September 2021 THE CONVERSATION uploaded this article by Ran Boydell, Visiting Lecturer in Sustainable Development, Heriot-Watt University, September 14, 2021.

Five numbers that lay bare the mammoth effort needed to insulate Britain’s homes

Ran Boydell writes:

Environmental activists recently blocked junctions of the M25 – London’s orbital motorway – to protest the glacial pace at which the UK government is tackling carbon emissions and fuel poverty in Britain’s housing stock.

Arguing that the country has “some of the oldest and most energy-inefficient” homes in Europe, the group known as Insulate Britain has vowed to continue campaigning until the government “makes a meaningful commitment to insulate Britain’s 29 million leaky homes”.

The transition to net zero emissions is often framed as a race to make new stuff – such as electric vehicles and wind turbines – as fast as possible. That’s actually the easy part. The hard part will be modifying what already exists – and that includes people’s homes.

Neutralising each home’s contribution to climate change will require a range of installations, including wall insulation, double- or triple-glazed windows, a heat pump or another low-carbon form of heating, and solar panels. Making these changes is known as retrofitting. The idea is to ensure that no home emits greenhouse gases by burning fossil fuels for energy and that, eventually, each home could produce as much energy as it uses.

Sound simple enough? Here are the five numbers that explain just how big a task it really is.

1. 68 million tonnes

About 15% of the UK’s total carbon emissions – 68 million tonnes – comes directly from homes, mostly from boilers burning gas for hot water and space heating. That’s more than the entire agricultural sector at 10%, and many times the 2% from industrial processes, such as cement, steel and chemical manufacturing in 2019.

2. 26 million

Some of the UK’s existing 29 million homes will be demolished by 205O, but it’s estimated that around 26 million will still be around. These will all have to be retrofitted to net zero standard.

To put that another way, about 80% of all the houses that will exist in 2050 are the houses that people are currently living in. Only 20% of the houses will have been built from scratch to net zero standard.

3. £26,000

The cost to retrofit a typical family home to net zero standard is estimated at about £26,000. This is based on an analysis of work by the Climate Change Committee – a body of experts that advises the UK government.

Multiply those 26 million homes by £26,000 and the overall price tag is £676 billion. Averaged over the next 25 years, retrofitting Britain’s homes could amount to £27 billion a year. That is about the same as the entire annual spend on home repairs and maintenance, and more than half as big as the market for new-build homes.

A mass retrofit campaign wouldn’t just be a step-change in the construction industry, it would be an entire additional sector. But it would also be time-limited. Once all existing homes are retrofitted, it will come to an end.

4. 20 years

How quickly savings from an investment repay the initial expense is known as the payback period. In theory, a net zero house could have zero energy bills, as it would save and generate as much energy as it uses. The average annual energy bill is £1,289, so the payback period for a £26,000 retrofit would be just over 20 years.

But the payback period for each individual retrofitting measure tends to be longer. Improving window glazing tends to pay for itself after about 40 years. Roof and wall insulation is even longer at 46 years. Solid wall insulation, which will address the single biggest source of heat loss for older houses, has a payback period of 16 years.

Calculating the payback period for a heat pump is more complicated, as it typically replaces gas in a boiler with electricity. These energy sources have very different cost structures. Currently, the UK has one of the cheapest gas prices in Europe, but one of the most expensive electricity prices.

When considering the financial payback on an investment in energy efficiency, most households will struggle to look beyond five years, perhaps 15 years at most. But considering energy efficiency measures purely in terms of financial payback will never stack up. They must be considered in terms of carbon payback. Carbon payback is how quickly the reduced carbon emissions from daily life in a net zero home take to make up for the carbon emissions that went into making and building all the different parts.

For a home retrofitted to net zero standard, the carbon payback might be about six years. For individual parts it can be even shorter: solar panels have a carbon payback period of just 1.6 years.

Infrastructure, like roads and railways, is the only stuff people build which counts its payback periods in decades. The government needs to think of a mass retrofit programme for our houses in those terms: as critical national infrastructure.

5. 20%

The VAT rate applied to any work on existing homes – whether it’s maintenance, extensions, or retrofitting – is 20%. While there are some exceptions where the rate is reduced to 5%, these are only available to a small range of homeowners, such as those over 60, and only where the works are exclusively for the sake of energy efficiency, rather than as part of a broader home-improvement project. So the use of this rebate is minimal.

For private homeowners who are required to pay for retrofit measures like wall insulation or heat pumps from their own pocket, the so-called “able to pay” market, that 20% VAT might represent more than £4,000 of the estimated £26,000 cost.

By comparison, building a new home is zero-rated for VAT. This creates a financial incentive to demolish and rebuild rather than retrofit.

There have been many attempts to make the government change the VAT rules on this, including a recent one supported by the banking sector, but so far without success.

Decarbonising Britain’s housing stock is a huge challenge, but also a huge opportunity. Kickstarting the home insulation and retrofitting programme will only happen with government support, it is simply not something that normal market mechanisms can drive. Let’s hope public pressure can convince the government to change course fast.

From "even worse" to the catastrophic?

Does a reasonable hope in 2021 turn to understandable despair in 2023?

A sad truth according to Pier Paolo Pasolini.

In response to actions by Insulate Britain and other groups such as Just Stop Oil the UK government has announced its aim to pass through a series of new measures to restrict the ability for groups to disrupt national infrastructure as a form of protest.

An injunction effective on 22 September 2021 and lasting to 21 March 2022 was granted to National Highways. The injunction prohibited demonstrators from "causing damage to the surface of or to any apparatus on or around the M25 including but not limited to painting, damaging by fire, or affixing any item or structure thereto". Protesters who break the injunction will be in contempt of court, which could result in a prison sentence of up to two years or an unlimited fine. However, Insulate Britain figures told The Guardian that they believed an injunction, prosecutions and other legal actions were being delayed by the government until after 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26). A spokesperson said: "We know that our government and institutions purport that we live in a democracy, so they don't want to have 50–100 climate protesters on remand when [the conference] starts". On 17 November 2021, nine protesters were imprisoned: one for six months, six for four months and one for three months. Emma Smart, one of the protestors imprisoned, started a hunger strike after sentencing and was moved to the hospital wing of HMP Bronzefield on the 13th day of her strike.

A "reactionary" reaction?

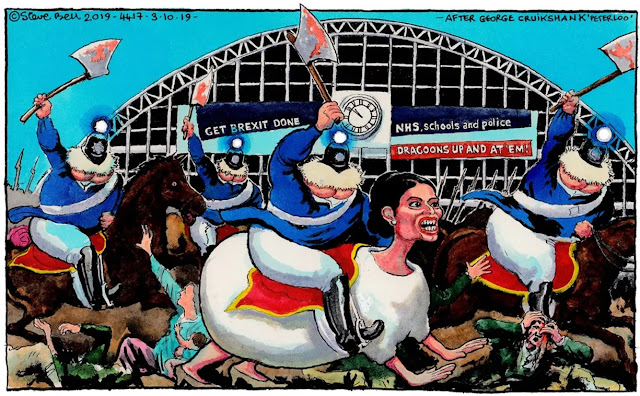

Steve Bell on Priti Patel, the home secretary, and her law and order agenda, with an acknowledgement to George Cruikshanks' cartoon of "Peterloo" (1819).

The Massacre of Peterloo or Britons Strike Home is Cruikshank's take on the charge of the Manchester Yeomanry on the unarmed populace in St. Peter's Fields, Manchester. The yeomanry are depicted as butchers armed with axes reeking with the blood of the victims. In the speech balloon top left it reads:

Down with 'em! Chop em down my brave boys: give them no quarter they want to take our Beef & Pudding from us! ---- & remember the more you kill the less poor rates you'll have to pay so go at it Lads show your courage & your Loyalty

In 2021 figures within the British government, including the Home Secretary Priti Patel, Transport Secretary Grant Shapps and Prime Minister Boris Johnson condemned the protesters' actions. The protests are supported by Green Party MP Caroline Lucas, and House of Lords members Natalie Bennett[ and Jenny Jones. On 4 October, Johnson said that Insulate Britain, who were not "legitimate protesters", were "irresponsible crusties". At the 2021 Conservative Party Conference, Patel announced increased penalties for motorway disruptions, criminalisation of infrastructure disruption and "stop and search" powers for the police. Patel named Insulate Britain specifically in her announcement. The Guardian opposed this policy as it would "remove even more rights from political protesters".

Just over a month ago this troubling story appeared in the Guardian in the aftermath of the trial of three non-violent Insulate Britain activist protesters.

Sandra Laville reporting for the Guardian (Wed 8 Mar 2023) writes under the headline and subheading:

Court restrictions on climate protesters ‘deeply concerning’, say leading lawyers

Three non-violent Insulate Britain activists have been jailed for telling juries why they were protesting

Restrictions placed on non-violent climate protesters who have been tried in criminal courts were part of a “deeply concerning” “pincer movement” narrowing their rights to free expression, leading lawyers have told the Guardian.

Three Insulate Britain activists are serving jail terms for contempt of court for breaching rulings made by a judge that they were not to mention the climate crisis, fuel poverty or the history of the peaceful civil rights movement to juries.

The three – David Nixon, Amy Pritchard and Giovanna Lewis – were jailed after addressing the juries at separate trials to explain their motivation for taking direct action.

They were on trial for public nuisance for taking part in a roadblock in the City of London in October 2021 as part of a campaign by Insulate Britain which says it wants to pressurise the government to insulate UK homes to reduce carbon emissions. Nixon was convicted of public nuisance. The jury failed to reach verdicts in the trial of Lewis and Pritchard and a decision is due on 31 March on whether a retrial will take place.

The rulings were made by Judge Silas Reid at Inner London crown court. Addressing the juries, the judge said the trials were not about climate change, or whether the actions of Insulate Britain and similar organisations were to be applauded or condemned, but whether or not the protesters caused a public nuisance. The defendants’ motivations for acting the way they did had no relevance, he said.

The Guardian understands similar rulings restricting freedom of expression defences available to peaceful protesters have been made at trials in other courts.

Katy Watts, a lawyer at advocacy organisation Liberty, said it was “deeply concerning” to see protesters imprisoned just for mentioning the reason for their actions. “We all have the right to stand up for causes we believe in. But we have seen a kind of pincer movement going on over the scope of convention rights in protest cases, which [is] increasingly narrowing our rights,” she said.

“The way that some protest trials, in particular those involving climate activists, have been managed has interfered with defendants’ rights to freedom of expression.”

Nixon, a care worker from Barnsley, was jailed for eight weeks for contempt of court after trying to explain to the jury at his trial the connection between insulation and tackling the climate crisis. Before being stopped by the judge, he said: “You’ve not been able to hear these truths because this court has not allowed me to say them.”

Nixon said later in court he had found the inability to explain to the jury why he had taken direct action “soul-destroying”. He was told he would serve half of his term in prison.

Reid told him the criminal courts were solely there to establish whether the prosecution had proven the guilt of defendants. “You said the court is not upholding what it is there to uphold,” he said. “You were wrong about that. This court is here to determine whether people have committed crimes.”

Pritchard and Lewis were each jailed last Friday for seven weeks for contempt. Lewis, a councillor from Dorset, told the court why she had breached the judge’s ruling. “There are thousands of deaths every year in the UK from fuel poverty, and thousands of deaths around the world due to climate change. There is no choice but to give voice to truth and to not be silenced,” she said.

Pritchard said: “Lack of political action means that ordinary people have to act.”

But the judge said the women each had disdain for the judicial process and had breached his ruling. “You have each been given the opportunity to apologise. Neither of you took that opportunity,” he said.

“My ruling was made because there was no relevance to the matters that the jury needed to decide. The public have rights as well as protesters.”

Tom Wainwright, a barrister from Garden Court chambers, said the growing concern being expressed at the removal of defences for protesters indicated the law may not have got the position right.

“The concerns raised about people’s ability to explain their motivations, and the consequences when they did, will, I think cause people to look again at this,” Wainwright said.

He went on: “A lot of protest cases all come down to the big question of where the boundary of freedom of expression lies.

“It is not a trump card which overrides the rights of others. A balance needs to be struck and I think it is one of the things a jury is ideally suited to consider.”

Insulate Britain hold a press conference outside the Home Office, London (22/9/2021).

As Extinction Rebellion shifts away from radical action and the UK government restricts the right to protest, the climate movement is asking tough questions. An opinion piece by Jack Shenker (Mon 6 Mar 2023) considers the existential question for climate activists:

Have disruption tactics stopped working?

On a bright, chilly morning in January, seven women – some young, some older, all condemned as guilty by the state – gathered at Southwark crown court.

The group had already been convicted of criminal damage following an Extinction Rebellion (XR) action in April 2021 that involved breaking windows at the headquarters of Barclays Bank: a financial institution responsible for more than £4bn of fossil fuel financing during that year alone. “In case of climate emergency break glass”, read stickers they stuck to the shattered panes. Now they were being sentenced. After a long preamble, the judge eventually handed down suspended terms, sparing the defendants jail for the time being. But he used his closing remarks to condemn their protest as a “stunt” that wouldn’t help to solve the climate crisis. “You risk alienating those who you look to for support,” he warned.

Is he right? Outside the courtroom, that’s a question XR has been pondering for some time. Two months ago, we received an answer of sorts: the movement released a statement on New Year’s Eve, dramatically titled “We Quit”, in which it announced it would “temporarily shift away from public disruption as a primary tactic” and promised that its next major action would “leave the locks, glue and paint behind”. Instead, it called upon anyone concerned about climate change to gather peacefully outside parliament on 21 April as part of a mobilisation that will “prioritise attendance over arrest and relationships over roadblocks”. In response, Just Stop Oil and Insulate Britain – the high-profile environmental action groups that have outflanked XR in recent years when it comes to disruptive public protests – both reasserted their commitment to direct civil resistance.

Debates over the pros and cons of different forms of activism are nothing new within the climate movement; see, for instance, fierce disagreements among supporters of Earth First! – arguably Britain’s first direct action environmental group – over the relative merits of sabotage nearly 30 years ago. What lends this one a particular urgency is the scale and pace of planetary destruction under the status quo (last year, the IPCC issued its “bleakest warning yet” regarding humanity’s future), as well as the specific conjunction of social, political and economic forces in the UK. After 13 years of Conservative rule, multiple and intersecting crises – from low pay and soaring inflation to unaffordable housing and a broken NHS – are engulfing the country, pushing more than a million people on to picket lines.

Rather than tackle the root causes of popular discontent, the government is seeking to criminalise those who give voice to it via new legal restrictions on the right to protest or take industrial action. Against a backdrop of both creeping authoritarianism above and collective fightbacks below, this feels like a moment of real possibility for climate campaigners, albeit one fraught with dangers.

Little wonder, then, that XR’s statement has heightened some existing tensions within the wider environmental movement, a landscape that ranges from militant tunnel-diggers to the philanthropic arm of corporate giants such as Ikea. When it first burst into the public consciousness back in 2018, bringing parts of London to a standstill in a nonviolent riot of music, dance and colour, XR was described in the mainstream press as a radical force, particularly as its political strategy rested on maximising arrests of its supporters. The fruit of its first “rebellion” included a formal declaration by the British parliament acknowledging the climate emergency, but subsequent mass actions delivered diminishing tangible returns and fuelled mounting concerns in some quarters about the nature of the group’s work.

One notoriously ill-advised intervention at London’s Canning Town station in 2019, which resulted in an ethnically diverse and largely working-class group of commuters dragging XR protesters from the roof of a tube train, seemed to visually embody the movement’s blind spots and failure to engage local communities.

In recent years, as prime-time news footage of pink boats at Oxford Circus has been supplanted by shots of protesters blocking the M25 or soup being hurled at (unharmed) Van Gogh masterpieces, other organisations have become the media face of supposedly extreme activism. Many of their supporters were once XR activists who have since broken away; at the same time, other prominent XR figures have moved in the opposite direction, calling for a less confrontational set of tactics that can command the broadest possible support base among the public. On the face of it, XR’s We Quit declaration looks like a big win for the latter, including the former XR spokesperson Rupert Read, who argues against “polarising” forms of activism and now co-directs an incubator dedicated to growing the environmental movement’s “moderate flank”.

The reality is more complicated. In truth, few believe that when it comes to the climate emergency there is a binary choice between radical protests and less confrontational forms of activism. Whether acknowledged or not, the former often depend upon the latter to make themselves and their demands appear more palatable to powerbrokers. There is already evidence of a positive symbiotic relationship between the “extreme” and “moderate” wings of the UK environmental movement, with Just Stop Oil interventions being found to increase public support for Friends of the Earth.

A more salient faultline – and one that runs right through the middle of many climate groups, including XR – concerns what exactly is being named as the enemy here, and therefore what sort of changes are needed to vanquish it. It’s easy enough to recognise that the environment is being devastated by human activity, but who is responsible: is it a generalised failure on the part of an entire species – or the result of specific actors, and specific political and economic systems built to enrich and protect them? If so, can we really expect concessions granted from within those systems to durably and meaningfully change our relationship with the natural world?

This question matters because alongside a healthy diversity of tactics and movement entry points, what the climate struggle needs is a clear, coherent narrative that knits together the many different ways in which those with enormous wealth are dispossessing the rest of us – including their war on the ecosystems that form the basis of our shared survival – and calls out the extractive, undemocratic structures that enable that process.

Yes, there absolutely must be room in the movement for people who would never dream of blocking a road or smashing a window, just as there must be for those willing to take on such risks. But there should be no space here for a “beyond politics” framing of the climate crisis (a slogan often and problematically espoused by XR, though its supporters insist that it has been misunderstood), because that would root the climate struggle in a fundamental lie. Without a compelling story that links rising sea levels with attacks on the right to strike, environmentalists will allow governments and businesses to pursue a slow, inadequate and ultimately ineffective decarbonisation programme.

Researching this article, I’ve spoken to people hailing from very different parts of the environmental movement, and what struck me most was the degree of mutual respect on display, rather than rupture. Rupert Read, for example, had positive things to say about some of Just Stop Oil’s past interventions; Indigo Rumbelow, a co-founder of Just Stop Oil, encouraged anyone who criticises her group’s tactics but supports their cause to join the XR mobilisation on 21 April. “The debate is not between those who want to take ‘moderate’ or ‘radical’ action,” she told me. “It’s between those who are standing by doing nothing at all, and those who are doing something. That’s where the line is drawn.”

The article's author Jack Shenker is a writer based in London and Cairo and a former Egypt correspondent for the Guardian. He is author of Now We Have Your Attention.

Just Stop Oil activists glue their hands to the wall after throwing soup at the Van Gogh painting Sunflowers at the National Gallery in London on 14 October 2022.

Following this Just Stop Oil tomato soup incident a suggestion that The National Gallery in London create a "cordon sanitaire" against potential activist attack with a banner declaring "Just Stop Oil" disregards a long backstory of art museums and questionable sponsorship arrangements.

Whilst the Guardian, in a rare example amongst global media organisations, has shown which side it's on when banning advertising from fossil fuel firms from January 2020, by contrast, management and board members interests among major art museums in the west have long been beneficiaries of funds from "big oil" and "big pharma" to "artwash" their brands and names, regardless of the catastrophic damage they continue to cause, both to the environment and society.

At last, but only recently in May 2022 last year, the National Gallery decided to remove the name of one of its largest donors from its walls, the Sackler family who profited from the opioid epidemic scandal in the US.

Meanwhile, the oil giant BP has directly sponsored the recent exhibition The World of Stonehenge at the British Museum, as well as its current Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt. The British Museum's Chair of the Trustees is George Osborne, the instigator of the Tory governments austerity measures for the UK from 2010 onwards, and until recently an advisor to the world's largest asset manager, BlackRock, with US$10 trillion in assets under management as of January 2022.

Part of the "artwash/greenwash" backstory is the "oil barons" connection to the founding of the Museum of Modern Art NY as a vehicle for their scions to upgrade their social status. In 1939, on the eve of the opening of the new building for the Museum of Modern Art on New York’s 53rd Street, an intrepid museum employee Frances Collins and a friend had concocted an invitation sent to seven thousand distinguished persons to the opening of the “Museum of Standard Oil.” Inside the invitation packet was a small card that read “Oil That Glitters Is Not Gold”. The overt allusion to then MoMA president Nelson Rockefeller’s deep entanglements in the world of oil did not amuse everyone. Collins promptly lost her job. But have things changed since then? Recent protests by Just Stop Oil are more remarkable in that they have been funded in part by an oil heiress. Aileen Getty, a philanthropist whose grandfather was the tycoon J Paul Getty, and who co-founded the Climate Emergency Fund, gifting it a very welcome $1m to be used by activists. But only $1m. Plus ça change!

Bad COP? Worse COP!

"Art-washing", "sports-washing", "green-washing", and now . . .

. . . COP-washing?

The 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference or Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC, more commonly referred to as COP27, was the 27th United Nations Climate Change conference, held from November 6 until November 20, 2022 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. It took place under the presidency of Egyptian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sameh Shoukry, with more than 92 heads of state and an estimated 35,000 representatives, or delegates, of 190 countries attending. It was the fifth climate summit held in Africa, and the first since 2016.

The conference was sponsored by Coca-Cola. Several environmental campaigners suggested this was greenwashing, given the company's contribution to plastic pollution. Coca-Cola is the largest plastic polluter in the world with 1.9 billion consumptions of Coca-Cola products per day around the world. This has led to three million tons of plastic packaging used by the Coca-Cola Company in one year. These plastic bottles are not biodegradable and are fabricated from toxic chemical compounds. For example, plastic Coca-Cola bottles demonstrated high levels of phthalate ester leaching. It is recommended to avoid drinking from plastic bottles that leach these chronic and highly toxic chemicals. Lack of proper disposal causes these bottles to be released into the environment. This has harmful consequences to animals if they ingest plastics and in environments such as degradation into microplastics. Coca-Cola is a multinational litter brand meaning its single-use plastic packaging has various consequences dependent on regional and national plastic regulations and/or laws. The company also has very high water usage despite its water neutrality pledge.

Al Jazeera's Federica Marsi published this story on 16 Nov 2022:

The first sign that something was amiss was in the bowl of rice. Residents in the town of Plachimada, in India’s state of Kerala, watched the grains swirl in gluey yellow water before taking a spoonful that left a metallic aftertaste.

Soon, they noticed that water had to be fetched deeper and deeper into the well. Crops withered and decreased in yield as stomach illness and skin rashes spread like a plague.

Eighteen years after their popular uprising shut down a Coca-Cola bottling plant accused of discharging toxic waste, Plachimada’s residents have taken to the streets again to denounce the company’s sponsorship of this year’s UN Climate Change Conference.

“Criminal Cola polluted our water and the same company is now sponsoring COP27,” a 50-year-old resident who identified himself as Thankavelu told Al Jazeera. “That’s why we are extremely angry.”

Thankavelu was among a group of protesters who burned the company’s symbols in front of the defunct plant run by Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages Limited – the Indian subsidiary of the Atlanta-based company – as the annual climate summit kicked off in Egypt last week.

For the past 20 years, their popular action group – the Anti-Coca Cola Struggle Committee – has demanded compensation from the company to no avail, despite the extent of environmental damage documented in several scientific studies.

In 2010, a High Power Committee mandated by the Kerala government found evidence of over-extraction of groundwater and indiscriminate disposal of sludge containing cadmium and lead.

“It is evident that the damages caused by the Coca-Cola factory at Plachimada have created a host of social, economic, health and ecological problems,” the report concluded.

The group sent a letter to UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres on November 4 to request the company’s removal from the COP27 sponsorship.

“This conference is for environmental protection and Coca-Cola are the polluter, not only here but in many places in India,” Biju said. “We are requesting that the UN take the reasonable step of removing the company from the climate negotiations.”

The government of Egypt announced on September 30 that it signed an agreement with Coca-Cola, introducing the company as a COP27 sponsor in Sharm El-Sheikh.

During the signing ceremony at the foreign ministry in Cairo, Ahmed Rady, Coca-Cola’s vice president of operations for North Africa, said it was the company’s “firm belief that working together through meaningful partnerships will create shared opportunities for communities and people around the world and in Egypt”.

A Coca-Cola spokesperson told Al Jazeera “in all our business activities, our bottling partners and we ensure compliance with all applicable laws as stipulated by the Government”.

The company also stated its sponsorship of COP27 was “in line with our science-based target to reduce absolute carbon emissions 25 percent by 2030, and our ambition for net zero carbon emissions by 2050”.

Watchdog organisations, however, argue its involvement runs counter to the United Nation’s frameworks and principles.

“Plachimada is one of many heart-wrenching examples of how Coca-Cola has historically exploited communities and further exacerbated struggles [caused by] the climate crisis,” Ashka Naik, the research director at Corporate Accountability, told Al Jazeera.

“The fact that our most vital intergovernmental forum for addressing the climate crisis is being sponsored by big polluters and its enablers makes a mockery of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),” Naik added.

This global beverage company markets itself as sustainable and environmentally friendly while being the largest plastic polluter in the world!

Washington, D.C. (June 8, 2021) — On the grounds of false and deceptive advertising, Earth Island Institute today filed a lawsuit against the Coca-Cola Company, the American multinational beverage corporation that portrays itself as sustainable and environmentally friendly while generating more plastic pollution than any other company in the world. The filing coincides with World Oceans Day, in recognition of the devastating impacts plastic pollution has on marine life, oceans, and coastal communities, and the dire need for companies like Coca-Cola to take responsibility for those impacts.

On its website and in advertising campaigns on television, in print, and across social media platforms, Coca-Cola claims that “our planet matters.” “Scaling sustainable solutions . . . and investing in sustainable packaging platforms to reduce our carbon footprint,” the company asserts. A “World Without Waste” declares the headline in one marketing campaign. Yet almost anywhere you look there’s a plastic Coca-Cola bottle trashing the public park, washed up on the beach, or piled in a mountain of plastic at a waste processing facility. What these advertising campaigns ultimately amount to is a mountain of greenwashing.

In fact, Coca-Cola was named the number one corporate plastic polluter for the past three years according to the Break Free From Plastic Global Cleanup and Brand Audit report. According to the report, 13,834 branded Coca-Cola plastics were recorded in 51 countries in 2020, reflecting more plastic than the next two top global plastic polluters combined.

“Coca-Cola has long been in the business of portraying itself as stewards of the environment while pointing to consumers as the source of plastic pollution. But it is Coca-Cola, not consumers, that chooses to use chart-topping amounts of plastic for its products. It is time this company is held accountable for deceiving the public,” said Earth Island Institute General Counsel Sumona Majumdar. “The more consumers become aware of plastic pollution, the more the company doubles down on its purported commitment to the environment to appease those concerns, but the actual results of their efforts tell a very different story. The company needs to come clean and be honest with consumers.”

Earth Island Institute has filed the case in the District of Columbia Superior Court, alleging that Coca-Cola is in violation of the District of Columbia’s Consumer Protection Procedures Act (CPPA). The CPPA is a consumer protection law that prohibits a wide variety of deceptive and unconscionable business practices. The statute specifically provides that a public-interest organization, like Earth Island, may bring an action on behalf of consumers and the general public for relief from the unlawful conduct directed at consumers. If successful, this lawsuit will prevent Coca-Cola from falsely advertising its business as sustainable, among other things.

“For 12 years we have advocated for a more just, equitable world free of plastic pollution and its toxic impacts, driving corporate responsibility to stop plastic pollution at the source,” said Julia Cohen, MPH, co-founder and managing director at Plastic Pollution Coalition, a project of Earth Island Institute and a global alliance of more than 1,200 organizations, businesses, and thought leaders in 75 countries. “We want the Coca-Cola company to stop the greenwashing and false claims, be transparent about the plastic they use, and be a leader in investing in deposit and refill programs for the health of humans, animals, waterways, the ocean, and our environment.”

As a fiscally sponsored project of Earth Island Institute, Plastic Pollution Coalition is at the organization’s core of educating consumers about plastic pollution, including in the District of Columbia, and engaging in advocacy related to environmental and human health impacts from plastic.

Plastic pollution is a global problem and threatens human and environmental health on a massive scale, from the plastic-producing petrochemical plants that disproportionately impact communities of color and low-income communities to the plastic waste that is often dumped in developing countries to the toxic microplastics invading our bodies, which have been shown to contribute to cancer, neurotoxicity, reproductive issues, endocrine disruption, and genetic problems. Consumers are becoming increasingly aware of these issues and are too often deceived by companies like Coca-Cola, which claims that they are reducing their plastic footprint on the earth.

From Earth Island to The Trash Isles

The Great Pacific garbage patch (also Pacific trash vortex and North Pacific Garbage Patch) is a garbage patch, a gyre of marine debris particles, in the central North Pacific Ocean. It is located roughly from 135°W to 155°W and 35°N to 42°N. The collection of plastic and floating trash originates from the Pacific Rim, including countries in Asia, North America, and South America.

Of the five gyres on this map, all have significant garbage patches.

Despite the common public perception of the patch existing as giant islands of floating garbage, its low density (4 particles per cubic metre (3.1/cu yd)) prevents detection by satellite imagery, or even by casual boaters or divers in the area. This is because the patch is a widely dispersed area consisting primarily of suspended "fingernail-sized or smaller" — often microscopic — particles in the upper water column known as microplastics. Researchers from The Ocean Cleanup project claimed that the patch covers 1.6 million square kilometres (620 thousand square miles) consisting of 45–129 thousand metric tons (50–142 thousand short tons) of plastic as of 2018. The same 2018 study found that, while microplastic dominate the area by count, 92% of the mass of the patch consists of larger objects which have not yet fragmented into microplastics. Some of the plastic in the patch is over 50 years old, and includes items (and fragments of items) such as "plastic lighters, toothbrushes, water bottles, pens, baby bottles, cell phones, plastic bags, and nurdles."

Research indicates that the patch is rapidly accumulating. The patch is believed to have increased "10-fold each decade" since 1945. The gyre contains approximately six pounds of plastic for every pound of plankton.

A similar patch of floating plastic debris is found in the Atlantic Ocean, called the North Atlantic garbage patch. This growing patch contributes to other environmental damage to marine ecosystems and species.

The South Pacific garbage patch

The South Pacific Gyre can be seen in the absence of oceanic currents off the west coast of South America.

The South Pacific garbage patch is an area of ocean with increased levels of marine debris and plastic particle pollution, within the ocean's pelagic zone. This area is in the South Pacific Gyre, which itself spans from waters east of Australia to the South American continent, as far north as the Equator, and south until reaching the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. The degradation of plastics in the ocean also leads to a rise in levels of toxicity in the area. The garbage patch was confirmed in mid-2017, and has been compared to the Great Pacific garbage patch's state in 2007, making the former ten years younger. The South Pacific garbage patch is not visible on satellites. Most particles are smaller than a grain of rice. A researcher said: "This cloud of microplastics extends both vertically and horizontally. It's more like smog than a patch".

Re:LODE Radio - Oceans and their boundaries along the LODE Zone Line

This video is part of the Re:LODE Radio Project that identifies a number of shoreline locations along the LODE Zone Line along a "great circle" that links the maritime cities of Hull and Liverpool. The animated imagery shows the zone along this "great circle". The video imagery includes unedited Super 8 clips of the shoreline locations where the LODE cargo of questions was created in 1992. The sequence begins with Friedrichskoog in Germany, and is followed by Puri in India: Glodok in Java; Pangandaran in Java; Port Hedland in Western Australia; Port Adelaide in South Australia; Port Melbourne and Port Albert in Victoria, Australia; Buenaventura and Santa Marta in Colombia; Slea Head, Dingle and Wicklow in Eire. The LODE and Re:LODE art projects of 1992 and 2017 point to the way increases in productive power press on population, and the way that capitalism as a system is the stumbling block to taking effective action against global warming.

So, from Port Albert in Victoria, Australia along the LODE Zone Line to Buenaventura in Colombia, includes this floating island mass of grain of rice sized particles of plastic called the South Pacific garbage patch.

DeSmog's article on Nov 16, 2022 by Stella Levantesi raises the concern that:

From software giants to soft drinks makers, the vast majority of partners at climate talks in Egypt are enmeshed with the oil and gas industry, researchers find.

Fossil Fuel-Linked Companies Dominate Sponsorship of COP27

Coca-Cola was the lead sponsor of the COP27 climate talks in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt.

Eighteen of the 20 companies sponsoring U.N. climate talks in the Egyptian resort of Sharm El-Sheikh either directly support or partner with oil and gas companies, according to a new analysis shared with DeSmog.

The findings underscore concerns over the role of the fossil fuel industry at the negotiations, known as COP27, which have become a focal point for deals to exploit African natural gas.

“These findings underline the extent to which this COP has never been about the climate: It’s been about rehabilitating the gas industry and making sure that fossil fuels are on the agenda,” said Pascoe Sabido of Brussels-based Corporate Europe Observatory, which co-produced the analysis with Corporate Accountability, a nonprofit headquartered in Boston.

“These talks are supposed to be about moving us away from fossil fuels, phasing them out,” Sabido told DeSmog.

A previous analysis by the two organisations and research and advocacy group Global Witness identified at least 636 fossil lobbyists who have been granted access to COP27 – an increase of more than 25 percent compared to the previous COP26 talks held in Glasgow a year ago; and twice the number of delegates from a U.N. body representing indigenous peoples.

“This is part of the bigger problem which is linked to the overall corporate capture of the U.N. climate talks,” Sabido said. “We need to kick big polluters out.”

Fiona Harvey in Sharm el-Sheikh and Ruth Michaelson in Istanbul report (Tue 22 Nov 2022) on:

Fears over oil producers’ influence with UAE as next host of Cop climate talks

And estimating that:

More than 630 fossil fuel lobbyists attended Cop27, and the Emirates, where Cop28 will be held, is a major oil and gas exporter.

Fears are growing among climate experts and campaigners over the influence of fossil fuel producers on global climate talks, as a key Gulf petro-state gears up to take control of the negotiations.

The United Arab Emirates, one of the world’s biggest oil exporters, will hold the presidency of Cop28, the next round of UN climate talks that will begin in late November next year.

Decisions taken at the Cop27 climate summit in Egypt, which finished on Sunday, showed the clear imprint of fossil fuel influence, according to people inside the negotiations. They said Saudi Arabia – an ally of Egypt outside the talks – played a key role in preventing a strong commitment to limiting temperature increases to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

Many countries, including the UK and the EU, were bitterly disappointed. Alok Sharma, the UK president of last year’s Cop26 summit, said in visible anger at the conclusion of Cop27 on Sunday morning: “Those of us who came to Egypt to keep 1.5C alive, and to respect what every single one of us agreed to in Glasgow, have had to fight relentlessly to hold the line.”

There were also at least 636 fossil fuel lobbyists attending the Cop27 talks in Egypt, of whom 70 were linked to UAE oil and gas companies.

This has raised questions over what will happen next year. Yamide Dagnet, director for climate justice at the Open Society Foundations, warned: “We expect the theme for Cop28 to include energy, alongside resilience [to the impacts of climate breakdown], finance and the global stocktake. So we should not be naive and assume that fossil fuel lobbyists will relent.”

Matthew Hedges, an expert on the Emirates’ political economy, who was imprisoned and tortured for almost six months in the UAE capital, Abu Dhabi, during his doctoral research, said there could be a conflict of interests.

“The Emirates is a country with some of the world’s largest oil reserves, with a desire to continue to expand and enhance fossil fuel production. There will be an effort to illustrate their engagement in renewables, particularly solar and nuclear, but there are questions to be asked about how you can engage in such conflicting actions,” he said.

About 13% of the UAE’s exports come directly from oil and gas, which represent about 30% of the country’s GDP. Many of its other industries, including construction and travel, are also financially linked to fossil fuels.

At Cop27, Saudi and other Gulf states, along with Brazil and China, are also said to have stymied attempts to include a resolution to phase down fossil fuels in the final outcome. Hedges said: “The UEA and Saudi Arabia have a very similar view on fossil fuels. Both depend on their ability to process and export oil.”

Alden Meyer, senior associate at the E3G environmental thinktank, said the final stages of Cop27, where negotiations ran more than 30 hours beyond the final deadline and were severely criticised by participants as “untransparent, unpredictable and chaotic”, should provide a lesson in what can happen when a Cop host nation allows fossil fuel interests to wield too much influence.

“It’s hard to imagine running a worse process than the Egyptian presidency,” he said. “The spotlight at Cop28 is going to be on 1.5C, and UAE are going to have to deal with that. Hopefully they will be more neutral than the Egyptian presidency.”

Nick Mabey, a founding director of E3G, was more optimistic. “UAE is not Egypt, and not Saudi Arabia. They have very different interests and wish to position themselves differently,” he said. “They’ve said very different things about fossil fuels. That hopefully means they will have a more balanced approach.”

UAE also has close relations with Russia, which is another source of concern. Since Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February, there has been a steady flow of Russian cash to UAE, including partnerships on energy and an increase in imports of Russian oil to enable UAE to export more of its own.

Russia, a leading oil and gas producer, is the world’s fourth biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, and has gas production facilities so leaky that they are a big source of the powerful greenhouse gas methane.

Paul Bledsoe, a former Clinton White House climate adviser now with the Progressive Policy Institute in Washington DC, said: “Russia is one of the nations that should be facing our opprobrium over Cop27. They should be ashamed of themselves, but I think Vladimir Putin is beyond saving. He has weaponised oil and gas for cash and for his geopolitical ends.”

Simon Stiell, the UN climate chief, is said to be scrutinising the Cop processes, with a view to ensuring their transparency and smooth running. He will be under pressure to ensure that the process of negotiation is less susceptible to fossil fuel interests.

The Guardian approached the UAE multiple times at Cop27 without response. UAE had a large pavilion at Cop27, and a delegation of about 1,000 members, which was twice as many as the next biggest delegation, that of Brazil.

The UAE government has declared its intention to reach net zero by 2050, and has invested heavily in renewable energy. The International Renewable Energy Agency is headquartered in Abu Dhabi.

From The Trash Isles to the tourism "bubble" of Sharm El Sheikh

Sharm El Sheikh commonly abbreviated to Sharm, is an Egyptian city on the southern tip of the Sinai Peninsula, in South Sinai Governorate, on the coastal strip along the Red Sea. The city and holiday resort is a significant centre for tourism in Egypt, while also attracting many international conferences and diplomatic meetings.

Sharm El Sheikh has, since the 1980's, been geographically connected to the rest of Egypt and the wider world by air transport. Sharm is a geographic outlier when it comes to the rest of Egypt, situated on a promontory overlooking the Straits of Tiran at the mouth of the Gulf of Aqaba. Its strategic importance led to its transformation from a fishing village into a major port and naval base for the Egyptian Navy. It was conquered by Israel during the Suez Crisis of 1956 and returned to Egypt in 1957. A United Nations peacekeeping force was stationed there until the 1967 Six-Day War when it was reoccupied by Israel. Sharm El Sheikh remained under Israeli control until the Sinai Peninsula was returned to Egypt in 1982 after the Egypt–Israel peace treaty of 1979. Egypt's then-president Hosni Mubarak designated Sharm El Sheikh as The City of Peace in 1982 and the Egyptian government began a policy of encouraging the development of the city. Egyptian businessmen and investors, along with global investors contributed to building several mega projects, including mosques and churches. The city is now an international tourist destination, and environmental zoning laws limit the height of buildings to avoid obscuring the natural beauty of the surroundings.

Naama Beach in Sharm and Tahrir Square 8 February 2011

As a tourism "refuge", somewhat removed from Egyptian general society and population, it is telling that amidst the 2011 Egyptian protests, the then-president Mubarak chose to escape the revolutionary turmoil in Cairo by reportedly flying to Sharm El Sheikh where he resigned the Presidency on 11 February 2011.

Oliver Milman writing for the Guardian (Fri 11 Nov 2022) under the heading:

On first week of summit there have been traffic jams, water shortages – and an atmosphere of state repression

With its jarring mix of sun-drenched luxury resorts, overt authoritarianism, apocalyptic climate warnings and sub-Arctic air conditioning, Sharm el-Sheikh has so far proved a challenging and confounding venue for the Cop27 climate talks.

The Egyptian resort town, perched on the edge of the Sinai peninsula overlooking the Red Sea, has long been a draw for tourists and there are still groups of Italian and Russian holidaymakers relaxing to thumping Europop, in a place studded by gaudy hotels and attractions that include a fake Roman amphitheatre, large model dinosaurs and a replica pyramid. “It’s like being in Las Vegas, but somehow worse,” muttered one Swedish Cop delegate.

For Cop delegates, however, the experience has often been bewildering as they funnel into the cavernous venue, the Tonino Lamborghini International Convention Center, a place that has at various times lacked food, water, internet connection or a bearable temperature between the blazing sunshine outside and the frigid temperatures generated indoors by hulking air conditioning units that resemble plane engines.

For the first two days, more than 30,000 delegates at the climate summit had to get by on nuts or bread smuggled in from hotels, with kiosks only selling overpriced coffees or the odd ice-cream to long lines of people waiting in the heat. By the third day, however, the smell of cooked food finally wafting across the convention centre was met with near jubilation. “I just haven’t eaten much here, it’s been hard,” said Jean Su, an American climate activist.

There have been other oddities. There is a dearth of maps and signage at the venue, leading to long, confused treks in search of national pavilions, or a toilet. Organisers’ good intentions in promoting recycling and a fleet of electric buses to transport delegates has resulted in rubbish being piled into recycling bins and lengthy traffic jams.

More serious issues abound outside the venue. The authoritarian regime of Abdel Fatah al-Sisi has sought to quell any sort of dissent that may erupt at Cop beyond generalised climate protests, with a small army of police, security guards and state Mukhabarat agents found throughout Sharm. Delegates travelling by road have been treated to the strange sight of Mukhabarat operatives in suits, sunglasses and earpieces standing alone every 100 metres or so in the middle of the broad, dusty fields that fringe the venue.

Climate activists hold a demonstration in Sharm el-Sheikh on Thursday 10 November 2022

Some activists have found this presence overbearing, with reports of surveillance, harassment and intense questioning of attendees to ascertain whether they are perceived troublemakers. Downloading the official Cop27 app, it turned out, required giving the Egyptian government access to users’ location and emails. Hotels, meanwhile, have hiked up their prices to astronomical levels, sometimes demanding more money from arriving delegates than was previously agreed.

Egyptians themselves have to deal with much worse and for far longer than a two-week conference, of course. Sanaa Seif, the sister of the jailed British-Egyptian hunger striker Alaa Abd el-Fattah, was a major focus of this security operation when she arrived at Cop27 on Tuesday to demand the release of her brother. Suspected plainclothes members of the Egyptian security services have tracked her movements and one pro-government MP, Amr Darwish, attempted to disrupt Seif’s press conference.

The atmosphere of barely concealed repression has hung over a conference that is, by its nature, a rather tortuous affair at the best of times. There was little optimism of a positive breakthrough by governments to act on the climate crisis beforehand and activists have again expressed frustration at the dawdling pace of progress by major polluters, particularly around the vexed issue of “loss and damage”, or payments from the wealthiest countries to developing nations that are bearing the brunt of heatwaves, drought, floods and other impacts. Loss and damage has been put on the agenda for the first time, in a win for developing countries.

There have been some notable rhetorical flourishes, not least from António Guterres, the UN secretary general, who has turned climate speeches into something of an art form. The world is on a “highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator”, he warned. “Humanity has a choice: cooperate or perish.”

Some of the leaders on the frontline of climate disasters cut through the diplomatic niceties that have pervaded a three-decade long process that has struggled to confront the gravity of the problem it was set up to solve. “You might as well bomb us, that might well have been an easier fate,” Surangel Whipps, the president of the Pacific nation of Palau, told fellow leaders. “The climate crisis is tearing us apart limb by limb.”

Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Barbados, has emerged as a major star of these summits and was afforded a seat alongside Sisi and Guterres at the opening ceremony of a summit that drew more than 100 world leaders. Mottley acts as a sort of conscience to the wealthy countries that have yet to provide the climate funding promised to ease the pain of island nations like hers.

“We were the ones whose blood, sweat and tears financed the industrial revolution,” she said in a lacerating speech that invoked colonialism. “Are we now to face double jeopardy by having to pay the cost as a result of those greenhouse gases from the industrial revolution? That is fundamentally unfair.”

Nina Lakhani Climate justice reporter for th Guardian (Fri 18 Nov 2022) writes under the heading:

Campaigners who interrupted US president’s speech had passes revoked after they put ‘lives in danger’

Four US activists who had their Cop27 accreditation revoked after briefly interrupting the US president, Joe Biden, in Sharm el-Sheikh have described the UN as “shameful” and say it has silenced Indigenous voices.

Big Wind, Jacob Johns, Jamie Wefald, and Angela Zhong missed the second week of the climate conference after being suspended for standing up with a “People vs Fossil Fuels” banner during Biden’s speech last Friday. The Indigenous activists, Wind and Johns, gave a war cry to announce themselves and draw attention to the fossil fuels crisis before security officials confiscated the banner. The group then sat down and Biden continued.

The activists appealed against the suspension to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), but the case has not yet been resolved.

“We’ve been locked out, our voices silenced,” said Johns, 39, a Washington state-based community organiser from the Akimel O’otham and Hopi tribe. “The climate collapse is coming, we are literally fighting for our lives. If we’re not allowed to advocate for our future, who will? It’s shameful.”

Wind, 29, an Indigenous conservation associate for Wyoming Outdoor Council and member of the Northern Arapaho tribe, said: “This is a clear example of radical Indigenous people and youth being silenced, we’re muted when we try to express our frustration in these spaces. It shows the UN’s true colours.”

Cop27 has been one of the most repressive – and expensive – UN climate summits on record. The Egyptian regime banned any unsanctioned protests or actions taking place inside or outside the conference centre. A handful of summit delegates have been arrested, deported and harassed, while hundreds of Egyptian civilians were arrested in Cairo amid rumours of brewing political protests. Price gouging has left grassroots activists struggling to raise funds to cover accommodation and food.

International spaces have been historically off limits to indigenous peoples, one of the activists said.

Inside the conference centre, known as the blue zone, plainclothes security officials have monitored the small authorised protests demanding climate justice and an end to fossil fuels. Government stooges interrupted panel events drawing attention to the plight of hunger striker Alaa Abd el-Fattah and Egypt’s 60,000 other political prisoners.

Ukrainian activists who earlier this week interrupted a Russian delegation event with shouts of “Russia is guilty of war crimes” were also suspended.

The four US activists, who had secured hotly sought-after tickets for Biden’s speech, said they wanted to call out false market solutions being pushed by the US and other western economies.

“Joe Biden is no climate hero. We wanted to create a moment on behalf of all frontline communities in the global north and south to demand real climate solutions,” said Wefald, a 24-year-old climate activist from Brooklyn.

After the brief interruption, they sat quietly through the remainder of the speech before being escorted out by UN security staff. John said: “The UN security said that our war call had put people’s lives in danger, and we were now deemed a security threat. Our badges were pulled and we had to leave.”

According to an email from the UNFCCC observer relations team, Biden’s speech was a US government event, and they only learned about the suspension from the Guardian’s live blog. The appeal, which was supported by the Indigenous Peoples’ Caucus and several nonprofits, remains unresolved.

Wind, who had been closely following negotiations on article 6, in which Indigenous people are fighting to ensure protections are built into carbon markets, said: “We are scared that carbon markets will take our lands away, and I should have been there making our concerns heard to the US delegation. I am worried about future Cops. It’s easy to label us as troublemakers so that our voices are not heard.”

Johns, who raised money through small individual donations to participate in Cop27 and was following loss and damage negotiations, is also part of the international Earthrise Collective of Indigenous wisdom keepers and thought leaders conducting prayers and meditations inside the blue zone.

“The world is falling apart but inside the destruction there is creation and a healthy liveable future, and we try to bring this energy to the chaotic negotiations. International spaces have been historically off limits to indigenous peoples, but different perspectives can hold a lot of power. I’ve been denied that basic right.”

A UNFCCC spokesperson said no advocacy actions were allowed inside plenary and conference rooms and that the four were suspended for breaking the code of conduct. “A final decision on the suspension shall be made after further inquiry of the issue,” they said.

The US delegation have been approached for comment.

These climate conferences just aren’t working

Bill McGuire's Opinion piece on Cop27 (Sun 20 Nov 2022) offers a critical but practical suggestion:

Rather than a bloated global talking shop, we need something smaller, leaner and fully focused on the crisis at hand

In the end, the recent shenanigans at the Cop27 meeting in Sharm el-Sheikh at least ended up making modest progress on loss and damage: high-emissions nations agreeing to pay those countries bearing the brunt of climate mayhem that they had little to do with bringing about.

But, yet again, there was no commitment to cutting the emissions accelerating this crisis, without which this agreement is nothing more – as one delegate commented – than a “down-payment on disaster”. No seasoned observers are of the opinion that the world is any nearer tackling the climate emergency. Indeed, the real legacy of Cop27 could well be exposing the climate summit for what it has become, a bloated travelling circus that sets up once a year, and from which little but words ever emerge.

It really does beggar belief, that in the course of 27 Cops, there has never been a formal agreement to reduce the world’s fossil fuel use. Not only has the elephant been in the room all this time, but over the last quarter of a century it has taken on gargantuan proportions – and still its presence goes unheeded. It is no surprise, then, that from Cop1 in Berlin in 1995, to Egypt this year, emissions have continued – barring a small downward blip at the height of the pandemic – to head remorselessly upwards.