The "beginning" and "The End" (by The Doors) of Apocalypse NowThe 1979 film Apocalypse Now, produced and directed by Francis Ford Coppola, was filmed in the Philippines. It's a connection to the Vietnam War and the expansionist, and essentially imperialist policy of the US, that cannot be avoided when it comes to understanding the place of the Philippines in the history of the centuries old globalised geopolitical landscape.

It's all about the inception of an American empire and its relation to a modern China.

This magnificent map of the Philippine archipelago, drawn by the Jesuit Father Pedro Murillo Velarde (1696–1753) and published in Manila in 1734, is the first and most important scientific map of the Philippines. The Philippines were at that time a vital part of the Spanish Empire, and the map shows the maritime routes from Manila to Spain and to New Spain (Mexico and other Spanish territory in the New World), with captions. In the upper margin stands a great cartouche with the title of the map, crowned by the Spanish royal coat of arms flanked each side by an angel with a trumpet, from which an inscription unfurls.

The map is not only of great interest from the geographic point of view, but also as an ethnographic document. It is flanked by twelve engravings, six on each side, eight of which depict different ethnic groups living in the archipelago and four of which are cartographic descriptions of particular cities or islands. According to the labels, the engravings on the left show: Sangleyes (Chinese Philippinos) or Chinese; Kaffirs (a derogatory term for non-Muslims), a Camarin (from the Manila area), and a Lascar (from the Indian subcontinent, a British Raj term); mestizos, a Mardica (of Portuguese extraction), and a Japanese; and two local maps — one of Samboagan (a city on Mindanao), and the other of the port of Cavite. On the right side are: various people in typical dress; three men seated, an Armenian, a Mughal, and a Malabar (from an Indian textile city); an urban scene with various peoples; a rural scene with representations of domestic and wild animals; a map of the island of Guajan (meaning Guam); and a map of Manila.

Among the Re:LODE (2017-18) A Cargo of Questions pages there is an article that explores the historical and spatial origins of the globalisation of trade. The heading for this article runs:

The Seven Seas referred to are not the oceans but the seas of the Dutch East Indies, the colonial territories that provided Dutch merchants and financiers with a monopoly on the spice trade. In the nineteenth century the Clipper Ship Tea Route from China to England was the longest trade route in the world. This route took sailors through seven seas near the Dutch East Indies: the Banda Sea, the Celebes Sea, the Flores Sea, the Java Sea, the South China Sea, the Sulu Sea, and the Timor Sea. So, the Seven Seas, in these quarters and during these times, referred to those seas, and if someone had sailed the Seven Seas it meant he had sailed to, and returned from, the other side of the world.

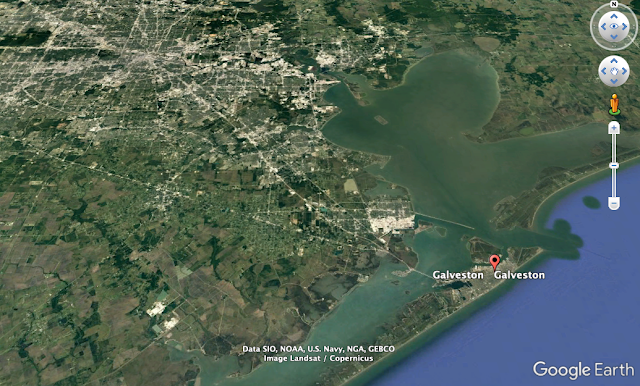

Manila is also referred to as "the world's first global city" as a result of the Manila Galleons trade route, arguably the first example of the globalisation of trade. In 2017, the Philippines established the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Museum in Metro Manila, one of the necessary steps in nominating the trade route to UNESCO as a UNESCO World Heritage project.In Peter Frankopan's book The Silk Roads - A New History of the World, the chapter 'The Road of Silver' sets out the way this trading route transformed world trade. China is ever present in this narrative, as are the multiple routes and connections that have shaped the modern world. The Spanish city of Manila was founded on June 24, 1571, by Spanish conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi, and is regarded as the city's official founding date.

In 1571, the foundation of Manila by the Spanish changed the rhythm of global trade; for a start it followed a programme of colonisation whose character was markedly less destructive for the local population than had been the case after the first Atlantic crossings. Originally established as a base from which to acquire spices, the settlement quickly became a major metropolis and an important connection point between Asia and the Americas. Goods now began to move across the Pacific without passing through Europe first, as did the silver to pay for them. Manila became an emporium where a rich array of goods could be bought.

This essentially Spanish trade route, often referred to as the silver road, carried an amount of silver originating in the Americas, then through the Philippines and on into the rest of Asia, that was truly staggering: at least as much passed this way as it did through Europe in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, causing alarm in some quarters in the Spanish Empire as remittances from the New World began to fall.

The silver road was strung round the world like a belt. The precious metal ended up in one place in particular: China. It did so for two reasons. First, China's size and sophistication made it a major producer of luxury goods, including the ceramics and porcelain that were so desirable in Europe that a huge counterfeit market quickly grew up. The Chinese, wrote Matteo Ricci while visiting Nanjing, 'are greatly given to forging antique things, with great artifice and ingenuity', and generating large profits thanks to their skill. China was able to supply the export market in volume and to step up production accordingly. The second reason why so much money flowed into China was an imbalance in the relationship between precious metals. In China, silver's value hovered around an approximate ratio to gold of 6:1, significantly higher than in India, Persia or the Ottoman Empire; its value was almost double its pricing in Europe in the early sixteenth century. In practice, this meant that European money bought more in Chinese markets and from Chinese traders than it did elsewhere - which in turn provided a powerful incentive to buy Chinese. The opportunities for currency trading and taking advantage of these imbalances in what modern bankers call arbitrage were grasped immediately by new arrivals to the Far East - especially those who recognised that the unequal value of gold in China and Japan produced easy profits.Peter Frankopan's book The Silk Roads - A New History of the World (pp 239-41)

In the chapter 'Cheap Money' in A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things - A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet by Jason W. Moore and Raj Patel (see Guardian Review), they look at this particular history of exchange:"Once again we can see cheapness at work. Cheap lives turned into cheap workers dependent on cheap care and cheap food in home communities, requiring cheap fuel to collect and process cheap nature to produce cheap money - and quite a lot of it. Potosi was the single most important silver source in the New World, and New World silver constituted 74 percent of the world's sixteenth century silver production. Silver does not make trade, but global trade can be traced from the mines of Potosi. Unless it forms parts of circuits of exchange, silver is just shiny dirt. It's the fusion of commodity production and exchange that turns it into capital. That's why some commentators have suggested that the birth year of global trade was 1571, when the city of Manila was founded. Silver from the New world didn't stay in Europe but was propelled along the spice routes and later across the Pacific. Japanese silver flowed to China from 1540 to 1620 as part of a complex network of exchange and arbitrage. Without the connection of exchange of silver for Asian commodities, money couldn't flow from the New World into East Asia. Because the Portuguese and then the Dutch controlled maritime silver flows through Europe to Asia, the Spanish short-circuited them, annually sending as much silver (fifty tons) across the Pacific and through Manila as they did across the Atlantic through Seville. Similar volumes of silver found their way to the Baltic. In eastern Europe, silver combined with credit, quasi-feudal landlords, and enserfed labor to deliver cheap timber, food, and vital raw materials to the Dutch Republic. To remember this is to insist that, although Europe features in it, capitalism's story isn't a Eurocentric one. The rise of capitalism integrated life and power from Potosi to Manila, from Goa to Amsterdam."(pages 84-85)

From an American western hemisphere to the Philippines. The spatial expansion of an American empire?

The Spanish Empire was set to disintegrate in the final decades of the nineteenth century, offering the United States an opportunity to expand its sovereign territories on a global as well a continental scale.

There had been numerous quasi-religious uprisings in the Philippines during the more than 300 years of colonial rule, but the late 19th-century writings of José Rizal and others helped stimulate a more broad-based movement for Philippine independence. Spain had been unwilling to reform its colonial government, and armed rebellion broke out in 1896. Rizal, who had advocated reform but not revolution, was shot for sedition on December 30, 1896; his martyrdom fuelled the revolution, led by the young general Emilio Aguinaldo.Thus the Philippine Revolution began in August 1896 and ended with the Pact of Biak-na-Bato, a ceasefire between the Spanish colonial Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera and the revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo which was signed on December 15, 1897. The terms of the pact called for Aguinaldo and his militia to surrender. Other revolutionary leaders were given amnesty and a monetary indemnity by the Spanish government in return for which the rebel government agreed to go into exile in Hong Kong.However, on the pretext of the failure of Spain to engage in active social reforms in Cuba, as demanded by the United States government, would lead to the cause for the Spanish–American War. American attention was focused on the issue after the mysterious explosion that sank the American battleship Maine on February 15, 1898 in Havana harbour. As public political pressure from the Democratic Party and certain industrialists built up for war, the U.S. Congress forced the reluctant Republican President William McKinley to issue an ultimatum to Spain on April 19, 1898. Spain found it had no diplomatic support in Europe, but nevertheless declared war; the U.S. followed on April 25 with its own declaration of war.Theodore Roosevelt, who was at that time Assistant Secretary of the Navy, ordered Commodore George Dewey, commanding the Asiatic Squadron of the United States Navy: "Order the squadron ...to Hong Kong. Keep full of coal. In the event of declaration of war Spain, your duty will be to see that the Spanish squadron does not leave the Asiatic coast, and then offensive operations in Philippine Islands." Dewey's squadron departed on April 27 for the Philippines, reaching Manila Bay on the evening of April 30.

The Battle of Manila Bay took place on May 1, 1898. In a matter of hours, Commodore Dewey's Asiatic Squadron defeated the Spanish squadron under Admiral Patricio Montojo. The U.S. squadron took control of the arsenal and navy yard at Cavite. Dewey cabled Washington, stating that although he controlled Manila Bay, he needed 5,000 additional men to seize Manila itself.

On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo proclaimed the independence of the Philippines at his house in Cavite El Viejo. Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista wrote the Philippine Declaration of Independence, and read this document in Spanish that day at Aguinaldo's house. On June 18, Aguinaldo issued a decree formally establishing his dictatorial government. On June 23, Aguinaldo issued another decree, this time replacing the dictatorial government with a revolutionary government (and naming himself as President).Within days, on the other side of the Pacific, the American Anti-Imperialist League had begun to take shape. This organisation, which opposed American involvement in the Philippines, grew into a mass movement that drew support from across the political spectrum. Its members included luminaries such as social reformer Jane Addams, industrialist Andrew Carnegie, philosopher William James, and author Mark Twain.Writing retrospectively in 1899, Aguinaldo claimed that U.S. Consul E. Spencer Pratt had verbally assured him that "the United States would at least recognize the independence of the Philippines under the protection of the United States Navy". In an April 28 message from Pratt to United States Secretary of State William R. Day, there was no mention of independence, or of any conditions on which Aguinaldo was to cooperate. In a July 28 communication, Pratt stated that no promises had been made to Aguinaldo regarding U.S. policy, with the concept aimed at facilitating the occupation and administration of the Philippines, while preventing a possible conflict of action. On June 16, Secretary Day cabled Consul Pratt with instructions to avoid unauthorised negotiations, along with a reminder that Pratt had no authority to enter into arrangements on behalf of the U.S. Government. Filipino scholar Maximo Kalaw wrote in 1927: "A few of the principal facts, however, seem quite clear. Aguinaldo was not made to understand that, in consideration of Filipino cooperation, the United States would extend its sovereignty over the Islands, and thus in place of the old Spanish master a new one would step in. The truth was that nobody at the time ever thought that the end of the war would result in the retention of the Philippines by the United States."On August 12, 1898, The New York Times reported that a peace protocol had been signed in Washington that afternoon between the U.S. and Spain, suspending hostilities between the two nations. The full text of the protocol was not made public until November 5, but Article III read: "The United States will occupy and hold the City, Bay, and Harbor of Manila, pending the conclusion of a treaty of peace, which shall determine the control, disposition, and government of the Philippines." After conclusion of this agreement, U.S. President McKinley proclaimed a suspension of hostilities with Spain.On the evening of August 12, the Americans notified Aguinaldo to forbid the insurgents under his command from entering Manila without American permission. On August 13, unaware of the peace protocol signing, U.S. forces assaulted and captured the Spanish positions in Manila. While the plan was for a mock battle and simple surrender, the insurgents made an independent attack of their own, which led to confrontations with the Spanish in which some American soldiers were killed and wounded. The Spanish formally surrendered Manila to U.S. forces.There was some looting by Insurgent forces in portions of the city they occupied. Aguinaldo demanded joint occupation of the city, however U.S. commanders pressed Aguinaldo to withdraw his forces from Manila. General Merritt received news of the August 12 peace protocol on August 16, three days after the surrender of Manila. Admiral Dewey and General Merritt were informed by a telegram dated August 17 that the President of the United States had directed that the United States should have full control over Manila, with no joint occupation permissible. After further negotiations, insurgent forces withdrew from the city on September 15.This battle marked the end of Filipino-American collaboration, as the American action of preventing Filipino forces from entering the captured city of Manila was deeply resented by the Filipinos.On August 14, 1898, two days after the capture of Manila, the U.S. established a military government in the Philippines, with General Merritt acting as military governor. During military rule (1898–1902), the U.S. military commander governed the Philippines under the authority of the U.S. president as Commander-in-Chief of the United States Armed Forces. After the appointment of a civil Governor-General, the procedure developed that as parts of the country were pacified and placed firmly under American control, responsibility for the area would be passed to the civilian.General Merritt was succeeded by General Otis as military governor, who in turn was succeeded by General MacArthur. Major General Adna Chaffee was the final military governor. The position of military governor was abolished in July 1902, after which the civil Governor-General became the sole executive authority in the Philippines.While the initial instructions of the American commission undertaking peace negotiators with Spain was to seek only Luzon and Guam, which could serve as harbours and communication links, President McKinley later wired instructions to demand the entire archipelago. The resultant Treaty of Paris, signed in December 1898, formally ended the Spanish–American War. Its provisions included the cession of the archipelago to the United States, for which $20 million would be paid as compensation. This agreement was clarified through the 1900 Treaty of Washington, which stated that Spanish territories in the archipelago which lay outside the geographical boundaries noted in the Treaty of Paris were also ceded to the U.S.On December 21, 1898, President McKinley proclaimed a policy of Benevolent assimilation with regards to the Philippines. This was announced in the Philippines on January 4, 1899. Under this policy, the Philippines was to come under the sovereignty of the United States, with American forces instructed to declare themselves as friends rather than invaders.The Treaty of Peace between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain, commonly known as the Treaty of Paris of 1898, was a treaty signed by Spain and the United States on December 10, 1898, that ended the Spanish–American War. Under it, Spain relinquished all claim of sovereignty over and title to Cuba and also ceded Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States. The cession of the Philippines involved a compensation of $20 million from the United States to Spain.

On the night of February 4, 1899, shooting erupted on the outskirts of Manila. Morning found the Filipinos, who had fought bravely, even recklessly, defeated at all points. While the fighting was in progress, Aguinaldo issued a proclamation of war against the United States. Anti-imperialist sentiment was strong in the United States, and on February 6 the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty that concluded the Spanish-American War by a single vote. U.S. reinforcements were immediately sent to the Philippines. Antonio Luna, the ablest commander among the Filipinos, was given charge of their military operations but seems to have been greatly hampered by the jealousy and distrust of Aguinaldo, which he fully returned. Luna was murdered, and on March 31 the rebel capital of Malolos was captured by U.S. forces.

Portion of the ruins of Manila, Philippines, after shelling by U.S. forces in 1899.

The Paris Treaty came into effect on April 11, 1899, when the documents of ratification were exchanged. It was the first treaty negotiated between the two governments since the 1819 Adams-Onís Treaty.The Treaty of Paris marked the end of the Spanish Empire, apart from some small holdings in Northern Africa and several islands and territories around the Gulf of Guinea, also in Africa. It marked the beginning of the United States as a world power. But there would be NO peace!The outbreak of hostilities in the so-called Philippine-American War, a war between the United States and Filipino revolutionaries from 1899 to 1902, led to an an insurrection that may be seen as a continuation of the Philippine Revolution against Spanish rule.

Filipino insurgents

In March 1900 U.S. Pres. William McKinley convened the Second Philippine Commission to create a civil government for the Philippines (the existence of Aguinaldo’s Philippine Republic was conveniently ignored). On April 7 McKinley instructed commission chairman William Howard Taft to “bear in mind that the government which they are establishing is designed not for our satisfaction, or for the expression of our theoretical views, but for the happiness, peace, and prosperity of the people of the Philippine Islands.” While nothing explicit was said about independence, these instructions were later often cited as supporting such a goal.Meanwhile, the Filipino government had fled northward. In November 1899 the Filipinos resorted to guerrilla warfare, with all its devastating consequences. The major operations of the insurrection were conducted in Luzon, and, throughout them, the U.S. Army was assisted materially by indigenous Macabebe scouts, who had previously served the Spanish regime and then transferred that loyalty to the United States. The organised insurrection effectively ended with the capture of Aguinaldo on March 23, 1901, by U.S. Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston. After learning of the location of Aguinaldo’s secret headquarters from a captured courier, Funston personally led an audacious mission into the mountains of northern Luzon. He and a handful of his officers posed as prisoners of war, marching under the guard of a column of Macabebe scouts who were disguised as rebels. Aguinaldo, who had been expecting reinforcements, welcomed the lead elements of the force only to be stunned by a demand to surrender. When Funston arrived, Aguinaldo remarked, “Is this not some joke?” before being led back to Manila.

U.S. troops in the Philippines during the Philippine-American War (1899–1902).

Although Aguinaldo pledged his allegiance to the United States and called for an end to hostilities, the guerrilla campaign continued with unabated ferocity. Brig. Gen. Jacob F. Smith, enraged by a massacre of U.S. troops, responded with retaliatory measures of such indiscriminate brutality that he was court-martialled and forced to retire. After the surrender of Filipino Gen. Miguel Malvar in Samar on April 16, 1902, the American civil government regarded the remaining guerrillas as mere bandits, though the fighting continued. About a thousand guerrillas under Simeón Ola were not defeated until late 1903, and in Batangas province, south of Manila, troops commanded by Macario Sakay resisted capture until as late as 1906.The last organised resistance to U.S. power took place on Samar from 1904 to 1906. There the rebels’ tactic of burning pacified villages contributed to their own defeat. Although an unconnected insurgency campaign by Moro bands on Mindanao continued sporadically until 1913, the United States had gained undisputed control of the Philippines, and it retained sovereignty over the archipelago of the islands until 1946.

Cheap lives?

Filipino casualties

The human cost of the war was significant. An estimated 20,000 Filipino combatants were killed, and more than 200,000 civilians perished as a result of combat, hunger, or disease. Of the 4,300 Americans lost, some 1,500 were killed in action, while nearly twice that number succumbed to disease.

The consequences of the images are the images of the consequences!

Page from Souvenir of the 8th Army Corps, Philippine Expedition. A Pictorial History of the Philippine Campaign, 1899.

A stepping-stone to China? An American Empire? The costs and the benefits?

And, after all, the Philippines are only the stepping-stone to China

Supporters of U.S. policy in the Philippines frequently reminded the American public that acquisition of a colony in Asia could open the door toward trade opportunities in China. This 1900 cartoon by Emil Flohri shows Uncle Sam bringing not only “education” and “religion” but a vast array of consumer goods to an eager Chinese population. The many signs on the Chinese shore itemise all the goods that presumably will find a market in China. The tiny Chinese figure dressed in traditional clothing follows the condescending stereotype demeaning non-Western, non-Caucasian peoples.

When it comes to this, the China-United States struggle for hegemony and the expansion of global power and influence has consequences for all, including along the LODE Zone Line.

Just as there was widespread opposition to the Vietnam War in the United States, and across the world, U.S. policy and the Spanish-American War elicited a strong anti-imperialist response from a wide section of American society. On June 2, retired Massachusetts banker Gamaliel Bradford published a letter in the Boston Evening Transcript in which he sought assistance gaining access to historic Faneuil Hall to hold a public meeting to organise opponents of American colonial expansion. An opponent of the Spanish–American War, Bradford decried what he saw as an "insane and wicked" colonial ambition among some American decision-makers which was "driving the country to moral ruin." Bradford's organiing efforts proved successful, and on June 15, 1898, his protest meeting against "the adoption of an imperial policy by the United States" was held.

The June 15 meeting gave rise to a formal four member organising committee known as the Anti-Imperialist Committee of Correspondence, headed by Bradford. This group contacted religious, business, labor, and humanitarian leaders from around the country and attempted to stir them into action to stop what they perceived as a growing menace of American colonial expansion into Hawaii and the former colonial possessions of the Spanish empire. A letter-writing campaign attempting to involve editors of newspapers and magazines was initiated. This initial pioneering effort by Bradford and his associates bore fruit on November 19, 1898, when the Anti-Imperialist Committee of Correspondence formally established itself as the Anti-Imperialist League.

The U.S. public was bitterly divided over the American conquest of the Philippines. While anti-imperialist critics denounced the invasion, supporters of the war defended it in terms of America’s destiny to spread civilization and progress to backward peoples and nations. In the rhetoric of the pro-war camp, the independence movement was commonly referred to as an “insurrection”.Even more vividly than in photographs, poems, and prose, the mystique of the white man’s burden found expression in a flood of colourful cartoons depicting the global spread of the Western world’s superior material as well as spiritual civilisation.

“If they’ll only be good. ‘You have seen what my sons can do in war — now see what my daughters can do in peace.’”

This graphic by S.D. Erhart, published in 1900 in the popular magazine Puck, depicts American colonialism as a benevolent form of uplift. As U.S. soldiers depart, Uncle Sam introduces a group of female teachers to the Filipinos, depicted in typical caricatures — here as childlike and half-naked — that suggested they were in need of education and civilisation. The U.S. government did send small numbers of teachers to the Philippines soon after acquiring the colony, but in reality, American troops outnumbered teachers throughout the military occupation.

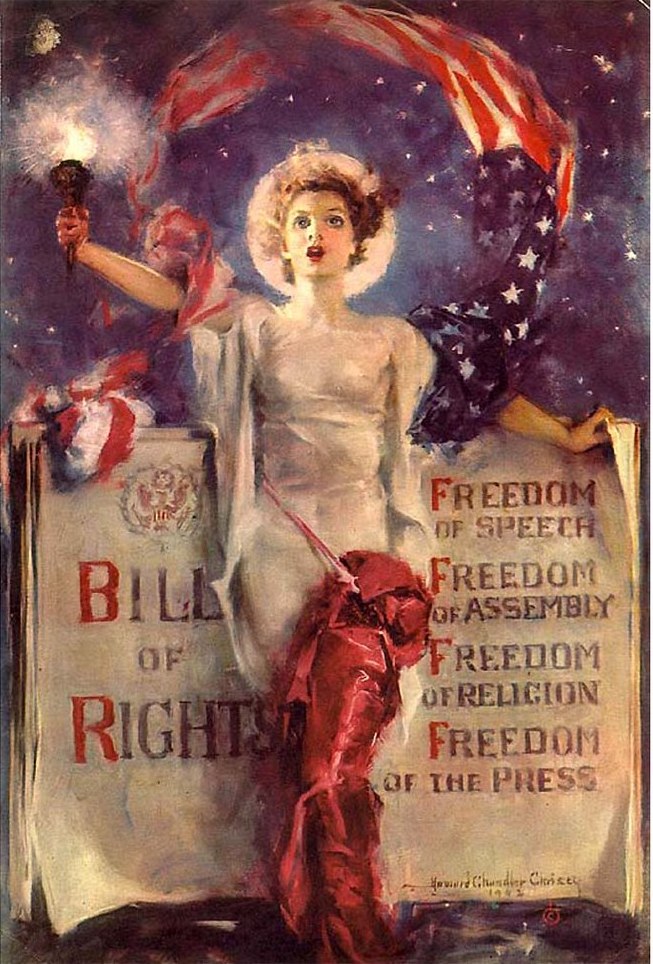

The female personification of agency in the civilising mission belongs to the many propaganda efforts where the stereoptypes generating images of "pretty girls" are mobilised in these ideological wars, actual wars and culture wars.

Howard Chandler Christy "Mother of His Country" 1932

The anti-imperialists opposed expansion, believing that imperialism violated the fundamental principle that just republican government must derive from "consent of the governed." The League argued that such activity would necessitate the abandonment of American ideals of self-government and non-intervention — ideals expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence, George Washington's Farewell Address and Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address.

In 1941, with war in the Pacific looming, it was these "values" that were trumpeted as the American "freedoms" in this image of Howard Chandler Christy's "pretty girl" personification of these sacred freedoms that were to be defended at all costs.

Female symbol of America holding torch in front of Bill of Rights and standing on "150 years" pedestal. Pastel drawing by Howard Chandler Christy, 1941. Library of Congress.

The Anti-Imperialist League was ultimately defeated in the battle of public opinion by a new wave of politicians who successfully advocated the virtues of American territorial expansion in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War and in the first years of the 20th century.

However important Americans may have felt it was to get to know the Philippines, they also felt it important to understand why Americans were there. As often as not, they drew on notions of civilisation and uplift that British poet Rudyard Kipling had conveyed in his famous 1899 poem “The White Man’s Burden,” in which Kipling urged Americans to “Take up the White Man’s burden” in the Philippines and “bind your sons to exile / To serve your captives’ need.”

This ca. 1900 studio photo of a baseball team in the Philippines conveyed a reassuring aura of normalcy for those worried about the well-being of American forces in the Philippines. (T. Enami Studio, Manila)

Soldiers posed for the camera with visages serious and calm. Some appeared as visual embodiments of President Theodore Roosevelt’s Kipling-esque call in an 1899 speech urging young American men to undertake “The Strenuous Life.” T.R. explained,Above all, let us shrink from no strife, moral or physical, within or without the nation, for it is only through strife, through hard and dangerous endeavor, that we shall ultimately win the goal of true national greatness.Americans in the Philippines understood colonial conquest as a burden to be carried by soldiers, missionaries, doctors, and teachers, and they frequently documented their personal sacrifices in images sent back home.

Americans who would never travel to the Philippines as soldiers, teachers, missionaries, or journalists had the opportunity to learn about the place from an explosion of books sold around the country during the Spanish-American War of 1898 and in the years that followed. The books promised an easily digestible introduction to the war’s campaigns, along with maps of the physical and cultural landscapes of America’s new island territories, all lavishly illustrated with photographs that took advantage of their status as honest guides to a far-off reality that most readers would never experience directly.

“There is truth-telling that should be prized in photography,” explained the author of one popular guide published as early as 1898 under the title The Story of the Philippines, The El Dorado of the Orient, “and our picture gallery is one of the most remarkable that has been assembled.” Another album titled Our New Possessions, put out that same year by a publisher of mass entertainments, mystery novels, and children’s books, interspersed images of war, destruction, and enemy corpses with landscapes and cozy scenes of camp life — as if to reassure Victorian Americans that their sons and brothers were upholding the standards of civilisation.

When it comes to the Vietnam War the same methods were employed, as in the example of the Playboy "playmate" G.I. Jo, a typical "girl next door", who visits Vietnam to "meet the troops". The article appeared in the May 1966 issue of Playboy.

Playboy magazine has its place in the much wider story of the Americanisation of the world, a place that is worthy of consideration, regardless of the obvious reservations concerning regressive aspects of patriarchy and misogyny. After all in this case, some examination is capable of revealing, or "unveiling", as it does, the dominant cultural shifts in the mess of our mass age (a mess-age and/or mass-age). Some of these aspects of what has been called a pornotropia are explored in this Re:LODE Radio page:

So, just what has been normalised?

Here's the story of GI Jo: The Story of One Playmate’s Visit to Vietnam in 1966

Cover girl Jo Collins signing photos for American GI's during her 1966 visit to meet troops during the Vietnam War

Most military strategists agree that, aside from actual firepower, nothing means more to an army than the morale of its men. And since the days of GI Joe, the American fighting man has seldom appeared on the frontiers of freedom without an abundant supply of that most time-honored of spirit-lifting staples: the pinup. From the shores of Iwo Jima to the jungles of Vietnam, the pinup queen has remained a constant companion to our men at arms; but the long-legged likenesses of such World War Two lovelies as Grable and Hay-worth have given way to a whole new breed of photogenic females better known as the playboy Playmates. It was only a matter of time, therefore, until centerfolddom’s contemporary beauties would be asked to do their bit for our boys in uniform. That time came last November, when Second Lieutenant John Price — a young airborne officer on duty in Vietnam — sent Editor-Publisher Hugh M. Hefner the following letter:

“This is written from the depths of the hearts of 180 officers and men of Company B, 2nd Battalion, 503rd Infantry, 173rd Airborne Brigade (Separate) stationed at Bien Hoa, Republic of Vietnam. We were the first American Army troop unit committed to action here in Vietnam, and we have gone many miles—some in sorrow and some in joy, but mostly in hard, bone-weary inches. …We are proud to be here and have found the answer to the question, ‘Ask what you can do for your country.’ And yet we cannot stand alone—which brings me to the reason for sending you this request.“The loneliness here is a terrible thing—and we long to see a real, living, breathing American girl. Therefore, we have enclosed with this letter a money order for a Lifetime Subscription to playboy magazine for B Company. It is our understanding that, with the purchase of a Lifetime Subscription in the U. S., the first issue is personally delivered by a Playmate. It is our most fervent hope that this policy can be extended to include us. …Any one of the current Playmates of the Month would be welcomed with open arms, but if we have any choice in the matter, we have unanimously decided that we would prefer . . .

. . . the 1965 Playmate of the Year — Miss Jo Collins.

“If we are not important enough…to send a Playmate for, please just forget about us and we will quietly fade back into the jungle.”

Deciding that only old soldiers should fade away, and deeply touched by the paratrooper’s plea, Hefner immediately began drawing up plans for the successful completion of Project Playmate. “When we first received the request,” Hef recalls, “we weren’t at all sure how the Defense Department would feel about Playboy sending a beautiful American girl into Vietnam at a time like this, but lieutenant Price’s letter was too moving to just put aside and forget. The lieutenant had obviously been a playboy reader for quite a while, since he remembered a special Christmas gift offer the magazine published several years ago, which stated that a lifetime subscriber from any city with a Playboy Club would have his first issue delivered in person by a Playmate. Of course we don’t have a Playboy Club in Vietnam at the moment, but we figured we could overlook that little technicality under the circumstances.”

Along with the usual complications and military restrictions any average civilian encounters when attempting to travel to Vietnam these days, many more technicalities had to be ironed out through the proper channels before Jo received the necessary Government clearance for a late-February flight to the front lines. “The fellows in Company B said it would be a privilege if I could visit them,” remarked the Playmate of the Year when asked how she felt about her upcoming tour of delivery duty in the war-torn Far East;

“but the way I see it — I’m the one who’s privileged.”

Roses are the order of the day as two members of Company B welcome Jo to Vietnam on behalf of their wounded Project Playmate officer, Lieutenant John Price, hospitalized back at battalion headquarters in Bien Hoa; Playboy’s pretty Vietnam volunteer visits Lieutenant Price’s wardmates at the Evacuation Hospital. “Most of them had been badly hurt,” says Jo, “but no one ever complained.”

Her call to arms came much sooner than expected, however, when word was received that Lieutenant Price had been wounded in action on January 3, and that her morale-boosting mission might have to be canceled unless Jo could reach the injured officer’s bedside at a Bien Hoa combat-zone hospital before his scheduled evacuation from Vietnam on January 13. All additional red tape still pending prior to Jo’s departure was quickly bypassed: On Sunday afternoon (January 9), Playmate First Class Collins and her party — which included playboy’s Playmate and Bunny Promotion Coordinator Joyce Chalecki as acting chaperone and staff photographer Larry Gordon — departed from San Francisco on a Pan Am jetliner bound for Saigon. Commenting on some of her own last-minute logistic problems before take-off, Jo later told us:

“Things were so hectic those last few days before we left that I was sure we’d never make it. For openers, I was away visiting friends in Oregon when the news came in about Lieutenant Price being wounded. The original plans called for my flying to Chicago in mid-February, where I would team up with Larry and Joyce, get my travel shots and clear up all the final details for the trip. Hef phoned me about the sudden switch in Project Playmate, and I spent the next five days flying back and forth—first to Seattle for my passport when I found out Oregon doesn’t issue them; then to Los Angeles, where I got my smallpox vaccination, checked out some last-minute details with my agent at American International Studios and raided my apartment for the clothes I figured I’d be needing. As it was, I managed to meet Larry and Joyce at the San Francisco airport and board our jet to Vietnam with all of about fifteen minutes to spare.” (In typical above-and-beyond-the-call fashion, trooper Collins — an aspiring actress whose recent film credits include minor roles in Lord Love a Duck and What Did You Do in the War, Daddy? — neglected to mention that, in reporting for duty on such short notice, she’d had to bypass an important audition for a principal part on TV’s Peyton Place.)

Some 8000 miles and 18 hours after their Stateside rendezvous, Jo and her playboystaffers landed at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut Air Base, where 400 American troops and a regiment of newsmen and photographers had turned out to greet them. After a brief review of her assembled admires, Jo was introduced to Lieutenant Clancey Johnson and Private First Class Marvin Hudson, two of Lieutenant Price’s friends in the 173rd Airborne Brigade who had ever-so-willingly volunteered to serve as a stand-in reception committee for their wounded buddy back at Bien Hoa. Mindful of his guerrilla training, Private First Class Hudson put on a one-man camouflage display when, after handing Jo her Company B (for Bravo) tribute of red roses, he subsequently blushed a deep crimson and succeeded in concealing the telltale lipstick print she had just planted on each of his cheeks.Following the deplaning festivities, the three playboy recruits were taken to a nearby “chopper” pad and given a whirlwind aerial tour of Saigon and the outlying districts aboard the “Playboy Special” — a Brigade helicopter especially renamed in honour of their visit. “That first chopper ride really started things off with excitement,” reports GI Jo. “It seemed as though we’d hardly even arrived, and there we were over hostile country being given our first taste of what they call ‘contour flying.’ That’s where you skim the treetops to prevent possible enemy snipers from getting a clear shot at you and then, suddenly, shoot straight up at about 100 miles per hour to 3500 feet so you can check the area for Viet Cong troop movements from outside their firing range. After our stomachs got used to it, we figured we were ready for just about anything.”

Jo takes a guided tour of Company B’s base-camp area, stopping off to admire the imaginative floor-to-ceiling Playmate motif adoring the PX (“It was the closest the fellows could come to a real Playboy Club”).

Back on terra firma, the Playboy troupe was joined by Jack Edwards, who took time out from his regular duties as Special Services Director for the Saigon-based press and military officials to act as the trio’s liaison man during its forthcoming three-day tour of the surrounding combat areas. As Jo later told us: “Jack was so concerned about our running into a V.C. ambush after we left Saigon that he wound up worrying enough for all of us. He managed to get us rooms at the Embassy Hotel in Saigon after our original reservations at the Caravelle somehow went astray; he kept press conferences down to a minimum so we could spend most of our time with the men at the front, arranged a first-night sight-seeing trip to some of the Saigon night clubs in case our own morale needed bolstering and, in general, watched over us like a mother hen. By the end of the first evening in Vietnam, we were all so pleased we’d come that, when one reporter reminded me I could end up getting shot during the next three days, I told him that the only shot I was still worried about was the one for cholera I was scheduled to get the next morning.”

A bit foot-weary during her first day at the front, Playmate First Class Collins hitches a ride with some armored admirers. Back to the company mess hall; seems pleased that an autographing gal can always find a strong back in Bien Hoa when she needs one.

The following day (Tuesday, January 11), Jo and her colleagues got a chance to test their calmness under fire. Arriving at Tan Son Nhut at 0830 hours, dressed in combat fatigues, they were issued bulletproof vests before boarding the “Playboy Special” with their MP escorts for an initial front-line foray. “I realize it was a question of safety before beauty,” says Jo, “but I couldn’t help feeling a little insecure. After seeing some of Saigon’s Vietnamese beauties Lieutenant Price referred to in his letter and catching a glimpse of myself in combat gear, I was afraid the guys wouldn’t be nearly as homesick for an American girl once they had a basis for comparison.” Flying low over enemy-infiltrated territory and encircled by three fully manned gun ships flying escort, the “Playboy Special” made its first stop at the 173rd Airborne Brigade Headquarters in Bien Hoa. Here, any fears our pretty Playmate might have harbored about her uniform appeal were summarily dispatched by the parade of smiling paratroopers waiting on the airstrip to greet her.

Most of the men of Company B were on jungle patrols during Jo’s first visit to Bien Hoa, but the one man most responsible for her being in Vietnam — Lieutenant John Price — was present and accounted for at his unit’s surgical ward. In spite of a severely wounded arm that will require several additional operations before it can be restored to full use, Lieutenant Price managed to muster up enough energy to give his favorite Playmate a healthy hug or two when she showed up to deliver his company’s Lifetime Subscription certificate and the latest issue of Playboy. The lieutenant’s initial reaction to seeing the Company B sweetheart standing there in the flesh was “Gosh, you’re even prettier than your pictures.” Flattered, Jo sealed her Playboy delivery with a well-timed kiss, and consequently convinced the company medics that Price was well along the road to recovery by evoking his immediate request for a repeat engagement. In fact, his condition seemed so improved that the doctors waived hospital regulations for the day to allow him to accompany Jo to lunch at Camp Zenn — the Company B base camp on the outskirts of Bien Hoa.

Jo lunches with Company B enlisted men, who show more interest in signatures than sustenance; After chow, she hoists their Bunny flag.

After lunch, Jo put her best bedside manner to use as she paid a brief call on each of the men in Lieutenant Price’s ward. “A few of the fellows asked me to help them finish a letter home, others wanted a light for their cigarette; but most of them just wanted to talk awhile with a girl from their own native land. A couple of times I was sure I would break down and bawl like a baby, but I managed to control myself until they brought in a badly wounded buddy who asked if he could see me before going into surgery. When I got to his side, he was bleeding heavily from both legs and I didn’t know what to do or say to comfort him. Then he looked up at me with his best tough-guy grin and simply said, ‘Hi, gorgeous.’ After that, I lost all control and the old tears really flowed.”

Before leaving Bien Hoa, Jo made additional bedside tours at the 93rd Medical Evacuation Hospital and the 3rd Surgical Hospital, where the doctors on duty decided to add some Playmate therapy to their own daily diet by piling into the nearest empty beds during her final rounds. Not until their day’s tour had ended and their chopper was warming up for the flight back to Saigon did Jo and her companions suddenly realize how close to actual combat they’d been for the past several hours. “We were all ready to go and standing outside the Brigade Officers’ Club when I first heard the sound of shots coming from fairly close by,” explains Jo. “Then a few mortar shells went off, but it still didn’t sink in how near the action we really were. I guess we’d all been too busy meeting wounded soldiers and talking to the men on the base to notice anything before. Then, right before our chopper lifted off, a series of flares went off and lit up everything for miles. I kept thinking how great it would have been if all those boys had been back home watching a Fourth of July celebration instead of out there in the jungle fighting for their very lives.”

Before leaving Bien Hoa, Jo makes a tour of other companies’ “Playboy Clubs” (“We ran across these ‘clubs’ at every GI base”). With her own whirlybird safely flanked by two gunships (left), Jo listens in on conversation between chopper jockeys.

GI Jo arrives at Special Forces camp atop Black Virgin Mountain.

Wednesday, the group headed out toward some of the more crucial combat zones in the Saigon military theater. First on the day’s itinerary was a stopover at Nu Ba Den, a strategic communications outpost under the command of Special Forces troops who had long since renamed their precarious hilltop position “Black Virgin Mountain.” Rising some 3200 feet above the surrounding countryside and under continuous assault from Viet Cong guerrillas hidden in the densely wooded areas below, Black Virgin Mountain is defended by a small detachment of Special Forces personnel and the South Vietnamese regulars placed in their charge. But despite the precariousness of their position, these wearers of the famed Green Berets greeted the Playboy group with a typical show of Special Forces readiness: crowning Jo upon arrival with her own green beret, escorting her to various lookout points around the installation and serving as interpreters when Vietnamese soldiers asked to meet her.

Visiting Playmate queen is crowned with a green beret (left) by Special Forces man assigned to this critical mountain outpost, signifying she bears this famed guerrilla-fighting group’s very special seal of approval; our GI Jo on-the-job instruction (right) in mortar firing.

From Black Virgin Mountain the “Playboy Special” flew its charges to the Special Forces encampment at Lay Ninth, whose boundaries encompass the majestic Cao Dai Temple — seat of the Cao Dai religion, which combines the teachings of Buddhism, Christianity and Confucianism. “The temple itself was right out of a fairy tale,” remembers Jo. “But its presence right in the middle of a combat theater made everything about it that much more strikingly unusual. We entered barefooted and were met by a different world, full of ornate columns, uncaged white birds and young headshaven priests, while just outside men in uniform walked about with their guns always ready at their sides.”

Another 85 miles over enemy lines brought the passengers of the “Playboy Special” to the village of Bu Dop, one of the most strategically critical military outposts in the entire Vietnam war zone. Located on the Cambodian border and protected by the 5th Special Forces Group, this vital base had, only three months earlier, been the scene of an ambush that cost the lives of all the men then assigned to its defense. “The Green Berets at Bu Dop went out of their way to try and maintain a relaxed air around us,” Jo later said, “but you could still cut the tension with a knife. We were introduced to just about everyone there was to meet—from the group commander to most of his American and South Vietnamese guerrilla fighters—but it seemed as though none of them ever left his field position or took his eyes off the surrounding jungle. Some of the edge was taken off our nerves when the village chief and his two wives came by to welcome us, since they all projected the feeling of complete calm by nonchalantly walking about the community with nothing on from the waist up.”

Whatever tranquilizing effect the sight of a Vietnamese village chieftain and his two topless ladies fair might have had on the threesome was short-lived, however, for the next stopover on their tour took them well outside the barbed-wire gates of Bu Dop and across the same jungle trail they had just been told was often swarming with Viet Cong. “Like most red-blooded female cowards,” jokes the 20-year-old Playmate of the Year, “Joyce and I hit the panic button the minute we caught sight of all the bullet holes in the side of our truck. And we both swear we saw Larry’s shutter finger shake through an entire roll of film, but he refuses to admit it.” As it turned out, the purpose of this overland junket into the unknown was to let some of Jo’s fighting South Vietnamese fans—stationed 15 minutes away in a small Montagnard hamlet — get a glimpse of their green bereted glamor girl before she left.The final item on Wednesday’s agenda was a flight to Vung Tau, a scenic coastal village on the Mekong Peninsula where American and South Vietnamese troops can enjoy a few days of muchneeded rest and rehabilitation before their next tour of duty in the interior. “At first,” says Jo, “I was afraid to ask any of the fellows how they felt about going back into combat after having a chance to get away from it all. I figured they’d all like to forget about war and just lie on the beach there until everything got settled. It didn’t take me long to find out otherwise. Many of our boys in Vietnam may only be 17-and 18-year-olds who don’t know much about world politics, but I came away from places like Vung Tau convinced that they know why they’re there. Nobody’s going to make them throw in the towel.”

Arriving at Bu Dop, a strategic supply base near the Cambodian border, Jo poses with fellow Green Berets (left) while Special Forces shutterbug in the foreground snaps away for post’s scrapbook. then meets General Williamson (right), who proclaims her the first female Sky Soldier.

Jo’s last day in Vietnam wound up being the busiest of all. With a gallant assist from Brigadier General Ellis W. Williamson — American Airborne Commander in Vietnam — she got a second chance to complete her mission as planned when the front-line troops from Company B were called back to Bien Hoa for a 24-hour lifetime subscribers’ leave and a long-awaited look at the Playmate of their choice. One by one, the combat-weary paratroopers filed off their choppers and hurried over for a hard-earned hello from Jo — a few even produced crumpled-up copies of her December 1964 Playmate photo they’d been carrying in their helmet liners in hope of someday having them autographed. “When I saw all those happy faces running toward me from every direction, I knew we’d finally gotten our job done,” she said.

One more trip to the front was on the agenda before Jo would be ready to head back to Saigon and a Hawaii-bound jet. Landing in War Zone D, Jo was escorted to combat headquarters, where a grateful general was waiting to hand her a farewell memento of her short stay in Vietnam — a plaque upon which had been inscribed the words: “Know ye all men that, in recognition of the fact that Playmate Jo Collins traveled to the Republic of Vietnam to deliver a Lifetime Subscription to playboy magazine to sky soldiers of the 173rd Airborne Brigade and demonstrated exceptional courage by volunteering to travel into hostile areas to visit its men and in doing so exhibited the all-the-way spirit typical of true airborne troopers…I, Brigadier General Ellis W. Williamson, do appoint her an honorary Sky Soldier, done this 13th day of January, 1966.”The day after her Saigon departure, Jo received further praise from high places for the job she had done. Between visits in Honolulu to Tripler Army Hospital and Pearl Harbor, she was called on the phone by Ambassador Averill Harriman, who wished to express his and Secretary of State Dean Rusk’s congratulations on all the good reports they’d heard concerning her morale-lifting mission. Needless to say, Jo was highly honored by the tributes of so dignified a brace of statesmen, but, as she put it, “The finest compliments I could ever receive have already been sent in the letters of over 200 fellows I was lucky enough to meet somewhere near Saigon.”It remained for the men of Company B to pay their Playmate postmistress the highest honor, however, by renaming their outfit “Playboy Company” and thus assuring Jo that her presence south of the 17th Parallel would not be soon forgotten. When asked how she felt about becoming the official mascot for this troop of front-line sky soldiers, a jubilant Jo replied, “I’ve never been prouder.” As the company’s new namesake, Playboy seconds that statement.

The "Apocalypse Now" Playmate scene is a dramatic construction!

The True Story of the 'Apocalypse Now' Playmate Scene

The reality was different, as the story about Jo Collins in her trip to Vietnam and covered in Playboy makes clear.

The Apocalypse Now version is set up to tell a different truth, using the crazy, surreal (as in hyper-real) situation of a Las Vegas style show helicoptered into a colonised and contested jungle. When it comes to show business and the Vietnam War, the reality was Bob Hope's annual USO tour of Southeast Asian military bases, including Vietnam, a reality emphatically situated in another age.

This video of Bob Hope's Christmas Special of 1967 features Raquel Welch, Elaine Dunn, Phil Crosby, Barbara McNair, and Miss World, Madeleine Hartog Bell.

Given that the difference in time between this USO tour of 1967 and the beginning of the filming of Apocalypse Now in 1976 was less than ten years, Francis Ford Coppola's film, constructed as it is, an exaggerated, surreal and dreamlike vision of a modern hell, the film is, as Coppola says in Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse, the 1991 American documentary film about the production of Apocalypse Now:

It's NOT about Vietnam! It IS Vietnam!

"We were in the jungle, there were too many of us, we had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little we went insane".

Yes, perhaps that is something of an explanation from Coppola, but Apocalypse Now is . . .

. . . NOT the Vietnam War!

It is a version of the usual, pure or impure . . .

. . . Eurocentric ideology!

Show business as usual?

The scene of Playmates performing in Apocalypse Now occurs about half way through the movie, and works dramatically to foreground a kind of symmetry that exists in the facts and history of the Vietnam War, and the process of making the film itself, show business.

The first half of the movie has echoes of the inspiration afforded to the director Coppola by Werner Herzog's Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), as much as the original concept that John Milius came up with for adapting the plot of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness to the Vietnam War setting.

The journeys along the rivers in Conrad's novella, and in Herzog's film, are journeys through "jungle", a kind of nature that, to the extent that it is "strange" and potentially hostile, a territory to be controlled, colonised yet resisting, so in its pristine and untameable state becomes a kind of enemy. The Indigenous People, inhabitants of a landscape, either to be conquered in a quest for a City of Gold, or in the Congo, mercilessly exploited for the trade in ivory and the monopolistic extraction of rubber from the forests, they are merges with this nature. They are an unseen enemy, invisible, with "primitive" projectiles, arrows and spears, wreaking havoc from its source, the jungle. A jungle that is itself the "unfamiliar", the "other", upon which countless paranoias, generated from the denial and guilt of the oppressor, are projected.

The fact of the racial "otherness" of Indigenous People in the project of the stabilisation of colonial appropriation in Vietnam, just as in the Amazon or the Congo, and along this other river, the Nung, includes a necessary process, fundamental to colonial and capitalist strategies, the de-humanisation of the "other". Or, as in the case of Apocalypse Now, a near complete erasure of the actual history of the Vietnamese peoples from the account.

Colonialist paranoia and the unidentified and invisible enemy

The costs of the Vietnam War

The first official death of an American in Vietnam was Technical Sergeant Richard Bernard Fitzgibbon Jr., United States Air Force, of Stoneham, Massachusetts, who was murdered by another U.S.A.F. airman on October 21, 1957.

The first US Army soldier to be killed in the line of duty in the Vietnam War was Capt. Harry Griffith Cramer, Jr., a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, who was killed near Nha Trang, Vietnam on October 21, 1957.

On July 8, 1959, while watching The Tattered Dress, five US Army officers became American casualties of the Vietnam War. The Viet Cong attacked the mess hall where Dale R. Buis, Chester M. Ovnand and three other officers were watching the movie. M/Sgt Ovnand, who was in charge of the projector, switched on the lights to change to the next reel, when Viet Cong guerrillas poked their weapons through the windows and sprayed the room with automatic weapons fire. M/Sgt Ovnand was hit with several 9mm rounds. He immediately switched the lights off and headed to the top of the stairs, where he was able to turn on the exterior flood lights. He died from his wounds on the stairs. Major Buis, at that time, was crawling towards the kitchen doors. When the exterior flood lights came on, he must have seen an attacker coming through the kitchen doors. He got up and rushed towards attacker, but was only able to cover 15 feet (4.6 m) before being fatally hit from behind.

His actions startled the attacker who was about to throw his satchel charge through the door. The attacker's satchel charge had already been activated and his moment of hesitation allowed the satchel charge to explode, killing him. Two South Vietnamese guards that were on duty that night were also killed by the Viet Cong. The wounded were, Captain Howard Boston (MAAG 7) and the Vietnamese cook's eight-year-old son.

Chester M. Ovnand and Dale R. Buis are listed Nos. 1 and 2 at the time of the memorial wall's dedication. Ovnand's name is spelled on the memorial as "Ovnard," due to conflicting military records of his surname.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs uses May 7, 1975, the Fall of Saigon, as the official end date for the Vietnam War era, but the last servicemen listed on the memorial timeline are the 18 U.S.servicemen killed on the last day of a rescue operation known as the Mayaguez incident with troops from the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

Named casualties? Un-named casualties? Unseen casualties?Invisible casualties?

On May 29 2017 US News reported that the names of three American service members were added to the wall this month.

The additions bring the total number of names on the memorial to 58,318.

The Wikipedia article on Vietnam War casualties states that:

Estimates of casualties of the Vietnam War vary widely. Estimates include both civilian and military deaths in North and South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

The war persisted from 1955 to 1975 and most of the fighting took place in South Vietnam; accordingly it suffered the most casualties. The war also spilled over into the neighboring countries of Cambodia and Laos which also endured casualties from aerial and ground fighting.Civilian deaths caused by both sides amounted to a significant percentage of total deaths. Civilian deaths were partly caused by assassinations, massacres and terror tactics. Civilian deaths were also caused by mortar and artillery, extensive aerial bombing and the use of firepower in military operations conducted in heavily populated areas.

Mỹ Lai massacre

Photo taken by United States Army photographer Ronald L. Haeberle on 16 March 1968, in the aftermath of the Mỹ Lai Massacre showing mostly women and children dead on a road.

A number of incidents occurred during the war in which civilians were deliberately targeted or killed. The most prominent of these events were the Huế Massacre and the Mỹ Lai Massacre.R. J. Rummel's mid-range estimate in 1997 was that the total deaths due to the Vietnam War totalled 2,450,000 from 1954–75.

Rummel calculated Viet Cong(VC) and People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) deaths at 1,062,000 and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and allied war deaths of 741,000, with both totals including civilians inadvertently killed.

He estimated that victims of democide (deliberate killing of civilians) included 214,000 by North Vietnam/VC and 98,000 by South Vietnam and its allies. Deaths in Cambodia and Laos were estimated at 273,000 and 62,000 respectively.

Nick Turse, in his 2013 book, Kill Anything that Moves, argues that a relentless drive toward higher body counts, a widespread use of free-fire zones, rules of engagement where civilians who ran from soldiers or helicopters could be viewed as VC, and a widespread disdain for Vietnamese civilians led to massive civilian casualties and endemic war crimes inflicted by U.S. troops. One example cited by Turse is Operation Speedy Express, an operation by the 9th Infantry Division, which was described by John Paul Vann as, in effect, "many My Lais".

Air force captain, Brian Wilson, who carried out bomb-damage assessments in free-fire zones throughout the delta, saw the results firsthand. "It was the epitome of immorality...One of the times I counted bodies after an air strike — which always ended with two napalm bombs which would just fry everything that was left — I counted sixty-two bodies. In my report I described them as so many women between fifteen and twenty-five and so many children — usually in their mothers' arms or very close to them — and so many old people." When he later read the official tally of dead, he found that it listed them as 130 VC killed

The Vietnamese? . . .

The use of another kind of derogatory terminology for Vietnamese people by U.S. military personnel, regardless of whether they were insurgent, innocent villager, or fighting a colonial war as a Viet Cong cadre would, generally apply. This was the derogatory term "gook", used by for people of Asian descent, a pernicious and de-humanising racial slur, a term that may have originated among U.S. Marines during the Philippine-American War (1899 – 1902). If so, according to the Wikipedia article:

It could be related to the use of "gook" as a slang term for prostitute during that period. Historically, U.S. military personnel used the word to refer to non-Americans of various races. The earliest published example is dated 1920 and notes that U.S. Marines then in Haiti used the term to refer to Haitians.

U.S. occupation troops in South Korea after World War II called the Koreans "gooks". After the return of U.S. troops to the Korean Peninsula, so prevalent was the use of the word gook during the first months of the Korean War that U.S. General Douglas MacArthur banned its use, for fear that Asians would become alienated to the United Nations Command because of the insult.

It acquired its current racial meaning as a result of movies dealing with the Vietnam War. Although mainly used to describe non-European foreigners, especially East and Southeast Asians, it has been used to describe foreigners in general, including Italians in 1944, Indians, Lebanese and Turks in the '70s, and Arabs in 1988.

In modern U.S. usage, "gook" refers particularly to communist soldiers during the Vietnam War and has also been used towards all Vietnamese and at other times to all Southeast Asians in general. It is a highly offensive-humanising and racist term.

In a highly publicized incident, Senator John McCain used the word during the 2000 presidential campaign to refer to his North Vietnamese captors when he was a prisoner of war:

"I hate the gooks. I will hate them as long as I live… I was referring to my prison guards and I will continue to refer to them in language that might offend."

A few days later, however, he apologized to the Vietnamese community at large.

The elision of a 19th century slang term for "a low prostitute" into a generalised and racial slur, especially against Southeast Asians in general, is part of a pernicious mixing and exchanging of sexual and sexualised terms with a racist and American exceptionalism, plus an added pinch of delusional superiority complex.

Do all lives matter? An American General explains . . .

This video montage cuts and pastes scenes from the award winning documentary film on the Vietnam War, Hearts and Minds (1974), directed by Peter Davis. The film's title is based on a quote from President Lyndon B. Johnson:

"the ultimate victory will depend on the hearts and minds of the people who actually live out there".The montage begins with an interview that takes place 1.43.09 into the film with General William Westmoreland — commander of American military operations in the Vietnam War at its peak from 1964 to 1968 and United States Army Chief of Staff from 1968 to 1972 — telling a stunned Davis that:

"The Oriental doesn't put the same high price on life as does a Westerner. Life is plentiful. Life is cheap in the Orient."

After an initial take, Westmoreland indicated that he had expressed himself inaccurately. After a second take ran out of film, the section was reshot for a third time, and it was the third take that was included in the film. Davis later reflected on this interview stating, "As horrified as I was when General Westmoreland said, 'The Oriental doesn’t put the same value on life,' instead of arguing with him, I just wanted to draw him out... I wanted the subjects to be the focus, not me as filmmaker."This interview is followed in the sequence by a clip of the napalm attack upon the village of Trảng Bàng during the Vietnam War on June 8, 1972.

The next cut taken from an earlier part of the Hearts and Minds film, documents American military personnel searching for paid sex on the streets of Saigon (0.14.51). The next cut (0.44.57) shows American military personnel interacting with Vietnamese sex workers. This sequence continues into scenes that shows American forces setting fire to Vietnamese villagers homes.

The next cut from the film Hearts and Minds (1.38.08) shows the collateral tragedy and human grief caused by the indiscriminate bombing campaign on the civilian population of North Vietnam. This sequence continues with scenes of grief and mourning for South Vietnamese military personnel at their funeral ceremonies. A sobbing woman is restrained from climbing into the grave after the coffin. This funeral scene is juxtaposed with the shocking interview with General William Westmoreland. This sequence is a repeats of the opening sequence of this montage, but continues with a sequence that shows the aftermath of the napalm attack on the village of Trảng Bàng. This includes film footage of the nine year old Phan Thị Kim Phúc OOnt, depicted in the Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph taken at Trảng Bàng by AP photographer Nick Ut, that shows her running naked on the road after being severely burned on her back by a South Vietnamese Air Force napalm attack.

This harrowing footage is followed by moving testimony from a U.S. veteran who explains that although he never used the horrific weapon of napalm he was responsible for dropping anti-personnel cluster bombs. He reflects on the possibility of his own children suffering a napalm attack and quietly breaks down in front of camera. The montage ends with the sound of grieving in the burial grounds of a cemetery.

Apocalypse Now, along with most dramas and documentaries on the Vietnam War, becomes an American story of an American war, an American madness, a madness, that like a virus, left unchecked, will destroy the world it seeks to dominate.

An American war and American casualties!

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is a U.S. national memorial in Washington, D.C., honouring service members of the U.S. armed forces who fought in the Vietnam War. The 2-acre (8,100 m2) site is dominated by a black granite wall engraved with the names of those service members who died as a result of their service in Vietnam and South East Asia during the war. The wall, completed in 1982, has since been supplemented with the statue The Three Soldiers and the Vietnam Women's Memorial.The instigation for this memorial came from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, Inc. (VVMF), incorporated as a non-profit organization, to establish a memorial to veterans of the Vietnam War. Much of the impetus behind the formation of the fund came from a wounded Vietnam War veteran, Jan Scruggs, who was inspired by the film The Deer Hunter, with support from fellow Vietnam veterans such as West Point and Harvard Business School graduate John P. Wheeler III. Eventually, $8.4 million was raised by private donations.On July 1, 1980, a site covering two acres next to the Lincoln Memorial was chosen and authorised by Congress where the World War I Munitions Building previously stood.

The chosen design for the monument was a proposal submitted by Maya Lin, the 21 year old undergraduate from Yale, studying architecture.

The public design competition saw 2,573 entrants register for selection with a prize of $20,000 as the competition award. On March 30, 1981, 1,421 designs were submitted. The designs were displayed at an airport hangar at Andrews Air Force Base for the selection committee, in rows covering more than 35,000 square feet (3,300 m2) of floor space. Each entry was identified by number only. All entries were examined by each juror; the entries were narrowed down to 232, then to 39. Finally, the jury selected entry number 1026, which had been designed by Maya Lin.

Her design specified a black granite wall with the names of 57,939 fallen soldiers carved into its face (hundreds more have been added since the dedication), to be v-shaped, with one side pointing toward the Lincoln Memorial and the other toward the Washington Monument The memorial was completed in late October 1982 and dedicated in November 1982.

According to Maya Lin, her intention was to create an opening or a wound in the earth to symbolize the pain caused by the war and its many casualties. "I imagined taking a knife and cutting into the earth, opening it up, and with the passage of time, that initial violence and pain would heal," she recalled.

Maya Lin's selected design proved controversial, in particular, its unconventional minimalist design quality, the use of the black granite as the dominant colour and its lack of ornamentation. Newspaper critics, politicians, and some veterans recoiled. Opponents blasted the design as "a black gash of shame," "a scar," even "a tribute to Jane Fonda." Two prominent early supporters of the project, H. Ross Perot and James Webb, withdrew their support once they saw the design. Said Webb, "I never in my wildest dreams imagined such a nihilistic slab of stone." James Watt, secretary of the interior under President Ronald Reagan, initially refused to issue a building permit for the memorial due to the public outcry about the design. However, since these early years, criticism of the Memorial's design has faded. In the words of Jan Scruggs, "It has become something of a shrine."

The timeline for the memorial begins on the 1st of November 1955, marked by the formation of the Military Assistance Command Viet Nam, better known as MACV.

One of the strategies that the Americans adopted in an attempt to defeat an "invisible enemy" was to deny the Vietcong the cover provided by the lush forest canopy in across Vietnam by deploying herbicides and defoliants to utterly remove and destroy it.

The costs of war, as the song has it . . .

For American servicemen and their families, along with the entire Vietnamese people, it turns out that . . .

. . . the actual "invisible enemy" was the U.S. government and U.S. capitalist corporations! And Agent Orange!

Dorothy Stratten, the Playboy Playmate of the Month for August 1979 and Playmate of the Year in 1980.

Behind the glamour (and tragedy) it was the Playboy Press that in 1980 published one of the first investigations into the impact of Agent Orange with Michael Uhl and Tod Ensign's book:

GI Guinea Pigs: How the Pentagon Exposed Our Troops to Dangers More Deadly Than War: Agent Orange and Atomic Radiation.

mm

These shocking revelations were picked up in the 1984 film Vietnam: The Secret Agent directed by Jacki Ochs, and pointing to the invisible agent dioxin.

"Dioxin, a compound found in Agent Orange, is recognized as the most toxic man-made chemical. We dumped it on Vietnam and we dumped it on the dusty backroads of Southern Missouri."

This video montage includes some clips from this film followed by a performance by Country Joe McDonald of the Agent Orange song.

". . . and I had to look . . . and to realise that my own government could have done this . . . that corporate America . . . for the love of the almighty dollar, had sacrificed my child."

"I didn't ask any questions when I was an 18 year old boy growing up on Long Island, but I am asking a hell of a lot of questions now, as a 34 year old man sitting paralysed in a wheelchair for the last 13 years dealing with an insensitive government that could care less if I lived or died, or these people here lived or died . . ."

Listen to the people! And then listen . . .

The Wikipedia article on the Effects of Agent Orange on the Vietnamese people The use of Agent Orange as a chemical weapon has left tangible, long-term impacts upon the Vietnamese people that live in Vietnam as well as those who fled in the mass exodus from 1978 to the early 1990s. Hindsight corrective studies indicate that previous estimates of Agent Orange exposure were biased by government intervention and under-guessing, such that current estimates for dioxin release are almost double those previously predicted Census data indicates that the United States military directly sprayed upon millions of Vietnamese during strategic Agent Orange use. The effects of Agent Orange on the Vietnamese range from a variety of health effects, ecological effects, and sociopolitical effects.

Accountability? Or, capitalism's culture of denial?

Difficulty in maintaining judicial and civil transparency persists despite decades passing since the use of Agent Orange by the United States military. Corporations indicted for their blindness to normal ethical standards have responded defensively and aggressively, in moves described as "antagonistic and focused on technological arguments" (Kernisky, Debra A (1997). "Proactive Crisis Management and Ethical Discourse: Dow Chemical's Issues Management Bulletins 1979-1990". Journal of Business Ethics).

The first legal proceeding taken on behalf of Vietnamese victims was undertaken in January 2004 in a New York district court. Ultimately the district court held that "herbicide spraying . . . did not constitute a war crime pre-1975" and that international law prevented the companies that produced Agent Orange from being liable.

Alternative models for reconciling the harms done by the dioxin on the Vietnamese people with reparations have also been proposed. Some have called for the defoliation and destruction to be deemed an "environmental war crime". Law reviews have even called for a revision to the litigation process in the US due to the harmful implications regarding justice, reparations, and accountability as a result of the political sway of large conglomerate, and connected private interests.

Since at least 1978, several lawsuits have been filed against the companies which produced Agent Orange, among them Dow Chemical, Monsanto, and Diamond Shamrock.

Attorney Hy Mayerson was an early pioneer in Agent Orange litigation, working with environmental attorney Victor Yannacone in 1980 on the first class-action suits against wartime manufacturers of Agent Orange. In meeting Dr. Ronald A. Codario, one of the first civilian doctors to see affected patients, Mayerson, so impressed by the fact a physician would show so much interest in a Vietnam veteran, forwarded more than a thousand pages of information on Agent Orange and the effects of dioxin on animals and humans to Codario's office the day after he was first contacted by the doctor. The corporate defendants sought to escape culpability by blaming everything on the U.S. government.In 1980, Mayerson, with Sgt. Charles E. Hartz as their principal client, filed the first U.S. Agent Orange class-action lawsuit in Pennsylvania, for the injuries military personnel in Vietnam suffered through exposure to toxic dioxins in the defoliant.