So, what's normal?

Women reading Cosmo? Men reading Playboy? Just look!

This is the magazine cover for the December/January 2020 issue of Cosmopolitan. The covers for this woman's magazine have, in recent years, prompted concerns in particular about its cover stories, which have become increasingly sexually explicit in tone, and using images on these covers with models wearing revealing clothes.

This cover includes items about "Here's when stuff will go back to normal-ish!!!", and "Never thought we'd print this but: dating lessons from pandemics past. The 14th century called and it wants its sex spree back".

The question of what is normal in 2020 has an added resonance in a time during a global pandemic and impending environmental catastrophe. So what has SEX got to do with it?

Just LOOK!

The New York Times featured this image in a story in 2015 about how retailers in the United States were shielding the covers of Cosmopolitan from view. This story was picked up later by Lydia Wheeler (08/07/15) in The Hill:

Retailers to shield customers from Cosmopolitan magazine

Cosmopolitan magazine has proven to be too risqué for some retailers.

Late last month, Rite Aid and Food Lion announced they were working to shield customers from the content on the magazine’s cover. In a statement, Rite Aid said it is still going to carry the publication, but future issues will be behind pocket shields. Food Lion, meanwhile, said it’s asking the publisher of the magazine to provide a screened holder.

"We encourage those with concerns about the content of this or other magazines to contact the publishers directly, as we believe this is the most effective way to address these matters,” the company said in a statement.

Now Wal-Mart is taking similar steps to protect customers. Wal-Mart spokesman Kory Lundberg said the company has provided stores with blockers for more than 10 years but has recently decided to send out a communication to remind stores about their use.

“We’re making sure the right people know this is available,” he said.

The National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCSE), which has been behind the push for the magazine cover-up, said Wal-Mart had become increasingly lax in enforcing the use of company-provided blinders in recent years.

The NCSE, which links pornography to sex trafficking, violence against women and child abuse, said the magazine targets children, yet continues to print adult content. Past Cosmo covers have donned headlines that include, “10 Things Guys Crave in Bed,” “His #1 Sex Fantasy” and “25 Sex Moves.”

“In its current issue, Cosmopolitan features a drawing by a sixth grade girl scout reader in the same issue that gives detailed descriptions of sexual acts for the purpose of pleasing a man,” NCSE Executive Director Dawn Hawkins said in a news release.

What's in a name?

The Cambridge Dictionary says that "cosmopolitan" means "containing or having experience of people and things from many different parts of the world", as in: New York is a highly cosmopolitan city. And Cosmopolitan as a magazine was first published and based in New York City in March 1886 as a family magazine; it was later transformed into a literary magazine and, since 1965, has become a women's magazine. It was formerly titled The Cosmopolitan.

What is now generally known as "Cosmo" was widely known as a "bland" and boring magazine by critics. Cosmopolitan's circulation continued to decline for another decade until Helen Gurley Brown became chief editor in 1965. She changed the entire trajectory of the magazine during her time as editor. Brown remodelled and re-invented it as a magazine for modern single career women completely transforming the old bland Cosmopolitan magazine into a racy, contentious and well known, successful magazine. As the editor for 32 years, Brown spent this time using the magazine as an outlet to erase stigma around unmarried women not only having sex, but also enjoying it.

In How Cosmo Changed the World, an article by Jennifer Benjamin for Cosmopolitan (May 3 2007), Helen Gurley Brown is quoted as saying:

"I knew that women were having sex and loving it," she says. "I wanted my magazine to be their best friend, a platform from which I could tell them what I'd learned and talk about all the things that hadn't been discussed before. I wanted to tell the truth: that sex is one of the three best things out there, and I don't even know what the other two are."

Known as a "devout feminist", Brown was often attacked by critics due to her progressive views on women and sex. She believed that women were allowed to enjoy sex without shame in all cases. She died in 2012 at the age of 90. Her vision is still evident in the current design of Cosmopolitan Magazine. The magazine eventually adopted a cover format consisting of a usually young female model (in recent years, an actress, singer, or another prominent female celebrity), typically in a low cut dress, bikini, or some other revealing outfit.

The magazine set itself apart by frankly discussing sexuality from the point of view that women could and should enjoy sex without guilt. The first issue under Helen Gurley Brown, July 1965, featured an article on the birth control pill, which had gone on the market exactly five years earlier.

This was not Brown's first publication dealing with sexually liberated women. Her 1962 advice book, Sex and the Single Girl, had been a bestseller. Fan mail begging for Brown's advice on many subjects concerning women's behavior, sexual encounters, health, and beauty flooded her after the book was released. Brown sent the message that a woman should have men complement her life, not take it over. Enjoying sex without shame was also a message she incorporated in both publications.

In Brown's early years as editor, the magazine received heavy criticism. In 1968 at the feminist Miss America protest, protestors symbolically threw a number of feminine products into a "Freedom Trash Can." These included copies of Cosmopolitan and Playboy magazines.

The dramatic, symbolic use of a trash can to dispose of feminine objects caught the media's attention. Protest organiser Carol Hanisch said about the Freedom Trash Can afterward, "We had intended to burn it, but the police department, since we were on the boardwalk, wouldn't let us do the burning."A story by Lindsy Van Gelder in the New York Post carried a headline "Bra Burners and Miss America". Her story drew an analogy between the feminist protest and Vietnam War protesters who burned their draft cards. Individuals who were present said that no one burned a bra nor did anyone take off her bra.The parallel between protesters burning their draft cards and women burning their bras were encouraged by organizers including Robin Morgan. The phrase became headline material.

The photograph above shows Dan Mouer in Vietnam in 1966. The magazine was sent by his wife, along with a batch of chocolate chip cookies.

The image was used in an Opinion piece by Amber Batura for The New York Times, with the headline:

How Playboy Explains Vietnam

There’s a famous scene about halfway through “Apocalypse Now” in which Martin Sheen’s river boat pulls into a supply base, deep in the jungle. While the crew members are buying diesel fuel, the supply clerk gives them free tickets to a show — “You know,” he says, “the bunnies.” Soon they’re sitting in an improvised amphitheater around a landing pad, watching as three Playboy models hop out of a helicopter and dance to “Suzie Q.”

The scene is entirely fictional; Playboy models almost never toured Vietnam, and certainly not in groups. But if the women were never there themselves in force, the magazine itself certainly was. In fact, it’s hard to overstate how profound a role Playboy played among the millions of American soldiers and civilians stationed in Vietnam throughout the war: as entertainment, yes, but more important as news and, through its extensive letters section, as a sounding board and confessional.Playboy’s value extended beyond the individual soldier to the military at large; the publication became a coveted and useful morale booster, at times rivaling even the longed-for letter from home. Playboy branded the war because of its unique combination of women, gadgets, and social and political commentary, making it a surprising legacy of our involvement in Vietnam. By 1967, Ward Just of The Washington Post claimed, “If World War II was a war of Stars and Stripes and Betty Grable, the war in Vietnam is Playboy magazine’s war.”The most famous feature of the magazine was the centerfold Playmate. The magazine’s creator and editor, Hugh Hefner, had a specific image in mind for the women he portrayed. The Playmate, originally introduced as the Sweetheart of the Month, represented the ultimate companion to the Playboy. She enjoyed art, politics and music. She was sophisticated, fun and intelligent. Even more important, this ideal woman enjoyed sex as much as the ideal man described in the publication. She wasn’t after men for marriage, but for mutual pleasure and companionship.

She enjoys art . . .

The sexualized, yet familiar, "girl next door" . . .

Though following in their legacy, the Playmate models differed from the pinups of World War II. Hefner wanted images of real women their readers might see in their everyday life — a classmate, secretary or neighbor — instead of the highly stylized and often famous women of an older generation. The sexualized, yet familiar, “girl next door” was the perfect accompaniment for soldiers stationed in Vietnam. This conception of wholesome, all-American beauty and sexuality acted out by largely unknown models reminded young soldiers of the women they left behind, and for whom they were fighting — and could, if they survived, imagine returning to.

The centerfold and other visual features in the magazine served another, unintentional purpose for American troops in Vietnam.

Playboy’s pictures and often-ribald cartoons conveyed changing social and sexual norms back home.

"Don't call me 'boy'!"

The introduction of women of color in 1964 with China Lee and in 1965 with Jennifer Jackson reflected shifting attitudes regarding race. Many soldiers wrote to both the magazine and the Playmates thanking them for their inclusion in Playboy. Black soldiers, in particular, felt that the inclusion of Ms. Jackson extended the promise of Mr. Hefner’s good life to them. Viewing these images forced all Americans to rethink their definitions of beauty.

Over time, the centerfolds pushed the boundaries of social norms and legal definitions as they featured more nudity, with the inclusion of pubic hair in 1969 and full-frontal nudity in 1972. The Washington Post reported that American prisoners of war were “taken aback” by the nudity in a smuggled Playboy found on their flight home in 1973.

The nudity, sexuality and diversity portrayed in the pictorials represented more permissive attitudes about sex and beauty that the soldiers had missed during their years in captivity.

Playboy’s appeal to the G.I. in Vietnam extended beyond the centerfold. The men really did read it for the articles. The magazine provided regular features, editorials, columns and ads that focused on men’s lifestyle and entertainment, including high fashion, foreign travel, modern architecture, the latest technology and luxury cars. The publication set itself up as a how-to guide for those men hoping to achieve Mr. Hefner’s vision of the good life, regardless of whether they were in San Diego or Saigon.For young men serving in Southeast Asia, whose average age was 19, military service often provided them their first access to disposable income. Soldiers turned to the magazine for advice on what gadgets to buy, the best vehicles and the latest fashions — products they could often then buy at one of Vietnam’s enormous on-base exchanges, sprawling shopping centers to rival anything back home.The magazine’s advice feature, “The Playboy Advisor,” encouraged men to ask questions on all manner of topics, from the best liquor to stock at home to bedroom advice to adjusting to civilian life. Troops found Playboy a useful tool in figuring out their roles in the consumer-oriented landscape they were now able to join because of the mobility and income their military service provided them.The content moved beyond lifestyle and entertainment as the editorial mission of the magazine evolved. By the 1960s, Playboy included hard-hitting features on important social, cultural and political issues confronting the United States, often written by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists, government and military leaders and top literary figures. The magazine took on topics like feminism, abortion, gay rights, race, economic issues, the counterculture movement and mass incarceration — something soldiers couldn’t get from Stars and Stripes. It offered exhaustive interviews with everyone from Malcolm X to the American Nazi leader George Lincoln Rockwell, exposing young G.I.s to arguments and ideas about race and African-American equality they might not have been introduced to in their hometowns. Service in Vietnam put many soldiers in direct contact with diverse races and cultures, and Playboy presented them new ideas and arguments regarding those social and cultural issues.As early as 1965, Playboy began running articles about the Vietnam War, with an editorial position that expressed reservations about the escalating conflict. The editors were smart about it, of course: Their stance may have been critical of the president, the administration, the military leaders and the strategy, but they made sure the contributors made every effort to stay supportive of the soldiers. In 1967, troops read the liberal economist John Kenneth Galbraith arguing that “no part of the original justification” for the war “remains intact,” as he dismantled the idea of monolithic Communism and other Cold War justifications for war. But that was different from attacking the troops themselves. In 1971, the journalist David Halberstam wrote in an article for Playboy that “we admired their bravery and their idealism, their courage and dedication in the face of endless problems. We believed that they represented the best of American society.” Troops in Vietnam could turn to Playboy for coverage of their own war without fearing criticism of themselves.Playboy was also useful as a forum for the men engaged in the fighting. The publication was unique in its number of interactive features. Soldiers wrote into sections like “Dear Playboy” for advice and with reactions to articles. But those correspondents also freely described their wartime experiences and concerns. They often described what they saw as unfair treatment by the military, discussed their difficulty in transitioning back to civilian society or thanked the magazine for helping them through their time in-country. In 1973, one soldier, R. K. Redini of Chicago, wrote to Playboy about his return home. “One of the things that made my Vietnam tour endurable was seeing Playboy every month,” he said. “It sure helped all of us forget our problems — for a little while, anyway. I thank you not only for myself but also for the thousands of other guys who find a lot of pleasure in your magazine.”In “The Playboy Forum,” another reader-response section, many wrote in addressing specific aspects of Hefner’s lengthy editorial series “The Playboy Philosophy,” including drugs, race and homosexuality in the military. The forum format allowed those who served in Vietnam to reach out not just to other soldiers, but also to the public, providing them a safe space to voice their opinions and criticisms of their service. “Traditionally, a soldier with a gripe is advised by friends to tell it to the chaplain, take it to the inspector general or write to his congressman,” a soldier wrote. “Now, probably because of letters about military injustice in The Playboy Forum, another court of last resort has been added to the list.”Playboy magazine’s significance to the soldiers in Vietnam spread far beyond the foldout Playmate. Troops appropriated the magazine’s bunny mascot and the company’s logo, painting it on planes, helicopters and tanks. They incorporated the logo into patches and “playboy” into call signs and unit nicknames. Adopting the symbol of Playboy was a small rebellion to the conformity of military life and a testament to the impact of the magazine on soldiers’ lives and morale.

And the magazine returned the favor. Long after the war ended, it funded documentaries on the war, Agent Orange research and post-traumatic stress disorder studies. It is a commitment that testifies to this enduring relationship between the publication and the soldier, and reveals how the magazine is a surprising legacy of one of America’s longest wars.

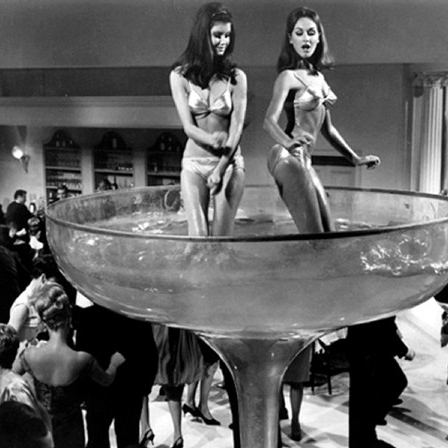

"Can anyone beat my pair?"

Double entendres are frequently featured in the world of the American pin-up girl, and would shape something of the future aesthetic of the pin-up in Playboy.

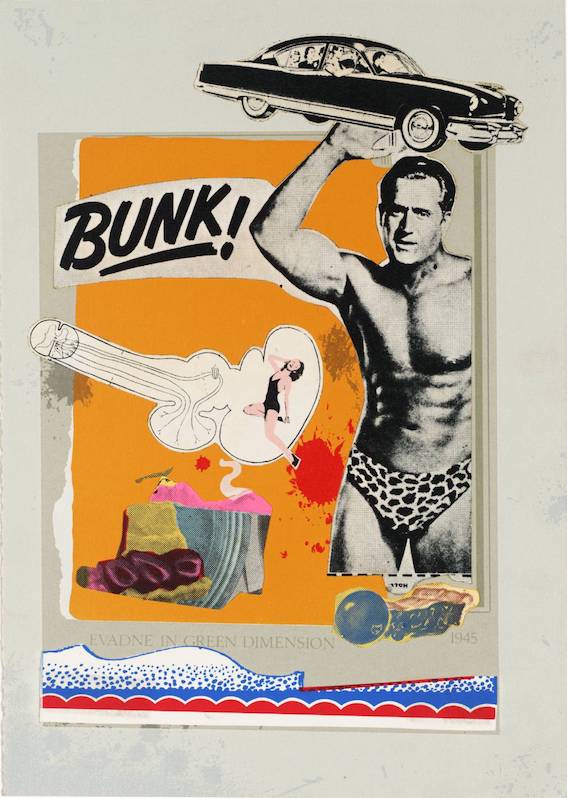

These techniques of ideological and industrial seduction and deception have a long history in the aesthetics that revel in aspects of sexual violence, and crucially associated with power and patriarchy.

The utilisation of the silent but obvious double entendre and explicit phallic symbolism, that's primarily about militant power in this poster, has a long back story.

Shock and/or/awe and Pornotropia?

The effect of this image is intended to encourage a connection between the aesthetic support systems of capitalist and imperialist power as an ideology steeped in another kettle (that's actually the same kettle), pornography!

Bringing out the big guns/dicks . . .

In this World of Warships YouTube channel video the persistence of this "trope" is what it is all about, and concluding with a "retro" escapist fantasy, a Hollywood pin-up inspired dance and music number taking place on the deck of a carrier.

The fantasy is extended to the inclusion of the "pretty girl" in a cosplay outfit on the World of Warships stand at the Tokyo Gaming Show, though admittedly the big guns are not so big, but the signification structure remains intact, with the cosplay girl's hand on a big symbolic phallus.

World of Warships stand at the Tokyo Gaming Show in 2014.

"Cosplay Is Not Consent", is the movement started in 2013 by Rochelle Keyhan, Erin Filson, and Anna Kegler, bringing to the mainstream the issue of sexual harassment in the convention attending cosplay community. Harassment of cosplayers include photography without permission, verbal abuse, touching, and groping.

In fantasy depictions, as in this example of the pornotropia of pornographer Julius Zimmerman a cosplay style nurse grabs a big penis and holds it to her big boobs.

Cosplay has influenced the advertising industry, in which cosplayers are often used for event work previously assigned to agency models. Some cosplayers have thus transformed their hobby into profitable, professional careers. Japan's entertainment industry has been home to the professional cosplayers since the rise of Comiket and Tokyo Game Show.

The phenomenon is most apparent in Japan but exists to some degree in other countries as well. Professional cosplayers who profit from their art may experience problems related to copyright infringement.

A cosplay model, also known as a cosplay idol, cosplays costumes for anime and manga or video game companies. Good cosplayers are viewed as fictional characters in the flesh, in much the same way that film actors come to be identified in the public mind with specific roles. Cosplayers have modeled for print magazines like Cosmode and a successful cosplay model can become the brand ambassador for companies like Cospa. Some cosplay models can achieve significant recognition. While there are many significant cosplay models, Yaya Han was described as having emerged "as a well-recognized figure both within and outside cosplay circuits". Jessica Nigri, used her recognition in cosplay to gain other opportunities such as voice acting and her own documentary on Rooster Teeth. Liz Katz used her fanbase to take her cosplay from a hobby to a successful business venture, sparking debate through the cosplay community whether cosplayers should be allowed to fund and profit from their work.

In the 2000s, cosplayers started to push the boundaries of cosplay into eroticism paving the way to "erocosplay". The advent of social media coupled with crowdfunding platforms like Patreon and OnlyFans have allowed cosplay models to turn cosplay into profitable full-time careers.

USS Missouri underway in August 1944.

The fetishising of "big guns" merges with history and ideology when it comes to the World of Warships story of the USS Missouri, and extends into science fiction fantasy with the film Battleship.

This newsreel film footage of General MacArthur on his way to receive the surrender of the Japanese aboard the USS Missouri anchored in Tokyo Bay has a whiff of triumphalism peppered with a pinch of revenge, and that casts a veil over the substantial fact that the war with Japan resulted in U.S. hegemony in the Pacific being put in question.

Any doubts as to the future of U.S. hegemony in the Asia Pacific region would have to be countered by all available means. The expected result would be a re-established "Pax Americana".

The use of this term "Pax Americana", latin for an "American Peace", originates in the 1890's, and echoes the use of the term "Pax Britannica", a term that recast the "Pax Romana", the 200-year-long timespan of Roman history which is identified as a golden age of Roman imperialism, order, prosperity stability, hegemonial power and expansion.

The use of this term is, in chronological order first:

The use of the term Pax Romana to pretend that peace is a benefit of empire.

That the late nineteenth century use of the terms Pax Britannica and Pax Americana are bound together in the shifting geopolitical patterns of global power, with a British Empire finding itself as a European colonial and imperialist power contending with an increasingly imperialist United States.

HANDS OFF!

"This in reality entails no new obligation upon us, for the Monroe Doctrine means precisely such a guarantee on our part" - President Roosevelt

A 1906 political cartoon depicting Theodore Roosevelt using the Monroe Doctrine to keep European powers out of the Dominican Republic.

The Goddess Pax appears as a "Calendar Girl" by pin-up artist Ted Withers in 1960.

The goddess Pax under Augustus Caesar was utilised as an ideological image, a demonstration that peace brought wealth, a contradiction, given that the traditional Roman understanding was that only war and conquest afforded wealth in the form of loot and plunder. Fruits and grains were incorporated into Pax’s image and this was maybe done to show the return and abundance of agriculture at the time, as many veterans during the empire where often settled onto farms - particularly after the civil wars. Pax was also shown with twins, maybe representing domestic harmony achieved through the Pax Romana. This was because fertility at home was spurred when the father of the household was around and not fighting in the legions. Cows, pigs and sheep imagery on the Ara Pacis showed the abundance of food and animal husbandry during the Pax Romana and these animals were also regularly scarified to Pax. Pax is also shown with a cornucopia to further emphasise the opulence and wealth during this Roman golden era. During the latter years of her worship she was very rarely shown holding the caduceus and she was increasingly shown sharing many more features common with Augustus - hinting at the Pax Augusta.

The Goddess Pax - Ara Pacis, Rome

"They that make them shall be like unto them!"

Q. Is this image uploaded below a pornographic image?

A. YES and NO!

YES, as in a dictionary definition of printed or visual material containing the explicit description or display of sexual organs or activity, but NOT as intended to stimulate sexual excitement.

The Guardian's Jonathan Jones article on Penises of the ancient world, references an article in Vice's Garage on the archaeological discovery of a mosaic found in a Roman toilet in Turkey depicting a young man holding his erect penis. Jonathan Jones writes:

When excavations began at the ancient Roman city of Pompeii in the 18th century, the place turned out to be full of penises. The ancient art preserved under ash from the 79 AD eruption of Vesuvius was so rich in willies that the English antiquarian Richard Payne Knight argued for the existence of an ancient fertility cult there. After all, there was one still alive in southern Italy at the time. His 1786 book An Account of the Remains of the Worship of Priapus has an engraved frontispiece showing an array of contemporary wax phalluses made as votive offerings.

More than 200 years later, the priapism of the ancient world can still astound us. Archaeologists have uncovered a Roman public toilet in southern Turkey with some filthy and funny floor decorations. As they hitched up their togas or reached for sponge on a stick, users of this men’s loo could look down at a mosaic of a young man holding his cock. He is labelled in the mosaic as Narcissus, who in Greek myth fell in love with his own reflection and wasted away gazing at it. Here, his attention is more focused: he’s obsessed with his own erection. As he plays with it, he looks sideways to reveal a ludicrous phallic nose.

Reports on this intimate uncovering show that for all our modern sophistication we can still be as amazed as 18th-century dilettanti were by ancient erotic art. One article even asks:

“Is this the first historical dick pic?

Re:LODE Radio seeks to offer a different account of the myth of Narcissus and Echo from the usual and common interpretation given by Jonathan Jones in his article, i.e. that:

"Narcissus, who in Greek myth fell in love with his own reflection and wasted away gazing at it."

Echo and Narcissus, 1630, by Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665)

Marshall McLuhan in his 1964 book Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, has a chapter, Chapter 4, titled:

THE GADGET LOVERThe subheading for this chapter is:

Narcissus as NarcosisMcLuhan writes:

The Greek myth of Narcissus is directly concerned with a fact of human experience, as the word Narcissus indicates. It is from the Greek word narcosis, or numbness. The youth Narcissus mistook his own reflection in the water for another person. This extension of himself by mirror numbed his perceptions until he became the servomechanism of his own extended or repeated image. The nymph Echo tried to win his love with fragments of his own speech, but in vain. He was numb. He had adapted to his extension of himself and had become a closed system. Now the point of this myth is the fact that men at once become fascinated by any extension of themselves in any material other than themselves. There have been cynics who insisted that men fall deepest in love with women who give them back their own image. Be that as it may, the wisdom of the Narcissus myth does not convey any idea that Narcissus fell in love with anything he regarded as himself. Obviously he would have had very different feelings about the image had he known it was an extension or repetition of himself. It is, perhaps, indicative of the bias of our intensely technological and, therefore, narcotic culture that we have long interpreted the Narcissus story to mean that he fell in love with himself, that he imagined the reflection to be Narcissus!Is the battleship's 16 inch gun an archetype of the Narcissus as narcosis effect, and a substitute version of the phallus, a tool of power, an extension of man?

When it comes to a dictionary definition of pornography, and the particular intention to stimulate sexual excitement, the "big dick" here is simply another example of "clickbait" on the internet, in this case pointing to the serious cultural, psychological and perceptual fallout that stems from the use of mechanical technological forms as powerful extensions of man. But everything has changed. As McLuhan said in the opening paragraphs of Understanding Media, back in 1964:After three thousand years of explosion, by means of fragmentary and mechanical technologies, the Western world is imploding. During the mechanical ages we had extended our bodies in space. Today, after more than a century of electric technology, we have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time as far as our planet is concerned. Rapidly, we approach the final phase of the extensions of man - the technological simulation of consciousness, when the creative process of knowing will be collectively and corporately extended to the whole of human society.

The intention here is, as with previous representations of a "big dick", to explore just how far a discussion like this can explore the extent to which a battleship is capable of becoming a fetishised "power and/or sex" thing in the service of ideology. Re:LODE Radio proposes for the sake of making a point; substitute the erect penis for a 16 in (406 mm) /50 caliber Mark 7 gun, and Julius Zimmerman's "pretty girl" for Cher!

Cher's performance of the pop rock song "If I could turn back time" among the big guns of USS Missouri for a video shoot that took place at the end of June, 1989, coincides with a period when the power politics underpinning the Cold War, and the accompanying contestation of spheres of influence, began to unravel. The lyrics of the song are about feelings of remorse following a reflection on past actions and a willingness to reverse time to make things right. If only!

Well . . . Hello Sailor!

The music video for Cher's "If I Could Turn Back Time", directed by American television director Marty Callner, shows Cher and her band performing a concert for the ship's crew. The video footage was shot on June 30, 1989.

Earlier that month tanks and troops had rolled into Tiananmen Square to crush the protests that were taking place there on 4 June 1989. Although they were not effectively organised and their goals varied, the students called for greater accountability, constitutional due process, democracy, freedom of the press, and freedom of speech. At the height of the protests, about one million people assembled in the Square. The Chinese Communist Party continues to forbid discussions about the Tiananmen Square protests and has taken measures to block or censor related information, in an attempt to suppress the public's memory of the Tiananmen Square protests. Textbooks contain little, if any, information about the protests. After the protests, officials banned controversial films and books and shut down many newspapers. Within a year, 12% of all newspapers, 8% of all publishing companies, 13% of all social science periodicals, and more than 150 films were either banned or shut down. The government also announced that it had seized 32 million contraband books and 2.4 million video and audio cassettes.[ Access to media and Internet resources about the subject are either restricted or blocked by censors. Banned literature and films include Summer Palace, Forbidden City, Collection of June Fourth Poems, The Critical Moment: Li Peng diaries and any writings of Zhao Ziyang or his aide Bao Tong, including Zhao's memoirs. However, contraband and Internet copies of these publications can still be found.

On the day following the massacre of protesters in Tiananmen Square a lone protester stepped in front of a column of tanks rolling down the northeast edge of Tiananmen Square, along Chang'an Avenue, shortly after noon . . .

Amazingly, the tank stopped. The protester then engages with the tank crew, then the CNN film footage ends. The incident was shared to a worldwide audience. Internationally, it is considered one of the most iconic images of all time, but inside China, the image and the accompanying events are subject to censorship.There is no reliable information about the identity or fate of the man; the story of what happened to the tank crew is also unknown. At least one witness has stated that Tank Man was not the only person to have blocked the tanks during the protest, but Tank Man is unique in that he is the only one who was photographed and recorded on video.

On the same day as the Tiananmen Square protests were being crushed by the Chinese Communist party, an election victory for Solidarity in the first partially free parliamentary elections in post-war Poland sparks off a succession of anti-communist Revolutions during 1989 across Central Europe, and later in South-East and Eastern Europe.

A "pretty girl" turning back time?

Cher's outfit for the original video, a fishnet body stocking under a black one-piece bathing suit that left most of her buttocks (and a tattoo of a butterfly) exposed, proved very controversial, and many television networks refused to show the video. MTV first banned the video, and later played it only after 9 PM. A second version of the video was made, including new scenes and less overtly sexual content than the original.

The outfit and risque nature of the video were a complete surprise to the Navy, who expected Cher to wear a jumpsuit for the concert, as presented on storyboards during original discussions with producers. The sailors were already in place and the band had begun playing when Cher emerged in her outfit. Lieutenant Commander Steve Honda from the Navy's Hollywood Liaison office requested Callner briefly suspend shooting and convince Cher to change into more conservative attire, but Callner, refused.The Navy received criticism for allowing the video shoot, especially from World War II veterans who saw it as a desecration of a national historic site that should be treated with reverence.

As the concerns over an "historic site" were being expressed by World War II veterans, the consequences of the Revolutions of 1989 and the adoption of a foreign policy based on non-interference by the Soviet Union, the Warsaw Pact was dissolved on 1 June 1991 and Soviet troops began withdrawing back to the Soviet Union, completing their withdrawal by the mid-1990s.Today the United States military, industrial and capitalist complex would probably dearly love to "turn back time" to 1945 or even 1898.

Cher cavorting amongst the big guns and sailors aboard the Missouri has the same "tongue in cheek" attitude of the many forms originating in American entertainment and popular culture.

It's a "put on" or putting "it" on as much as it's a "take off" or taking "it" off!

And "it", in both cases, is the audience for the artist/performer, the observer, whether participant observer or observant participant, or as in this famous line, referenced in T.S. Eliot's poem The Waste Land (1922), from one of the poems in Charles Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal and addressed to the reader:

Au Lecteur

Hypocrite lecteur, — mon semblable, — mon frère!Hypocrite reader! — My twin! — My brother!

Frontispiece for Baudelaire's collection of poems "Les Fleurs du Mal" 1857 by Félix Bracquemond.

A skeletal spectre of death is depicted in this image, arising out of the dung heap of modernity, covered with new but sickly vegetation, The Flowers of Evil.

For Baudelaire, the city has been transformed into an anthill of identical bourgeois that reflect the new identical structures that litter a Paris he once called home but can now no longer recognise, following Haussmann's renovation of Paris. Together, the poems in Tableaux Parisiens act as 24-hour cycle of Paris, starting with the second poem Le Soleil (The Sun) and ending with the second to last poem Le Crépuscule du Matin (Morning Twilight). The poems featured in this cycle of Paris all deal with the feelings of anonymity and estrangement from a newly modernised city, following th demolition of some of the old medieval districts.

Baudelaire is critical of the clean and geometrically newly laid out streets of Paris which alienate the unsung anti-heroes of Paris who serve as inspiration for the poet: the beggars, the blind, the industrial worker, the gambler, the prostitute, the old and the victim of imperialism. These characters whom Baudelaire once praised as the backbone of Paris are now eulogized in his nostalgic poems.

NOT "the prostitute"!

The Romans had adapted the myths and iconography of Venus from her Greek counterpart Aphrodite for Roman art and Latin literature. In the later classical tradition of the West, Venus became one of the most widely referenced deities of Greco-Roman mythology as the embodiment of love and sexuality, and usually depicted nude in paintings.

From antiquity . . .

Fresco from Pompei, Casa di Venus, 1st century AD. It is supposed that this fresco could be the Roman copy of famous portrait of Campaspe, mistress of Alexander the Great.

. . . to the Paris Salon of 1863

The Birth of Venus (French: Naissance de Venus) is a painting by the French artist Alexandre Cabanel.

Shown to great success at the Paris Salon of 1863, The Birth of Venus was immediately purchased by Napoleon III for his own personal collection. The Birth of Venus was one of a multitude of female nudes. Bathed in opalescent colours, the goddess Venus shyly looks to the viewer from beneath the crook of her elbow.

Olympia - a prostitute

Two years later, Manet presented his now renowned painting Olympia at the Salon.

Today both hang in the Musee’d’ Orsay. Unlike Venus's ethereal-like palette, Manet painted Olympia with pale, placid skin tone, and darkly outlined the figure. Her only seemingly modest gesture is her placement of her hand over her leg, though it is not out of shyness- one must pay before they can see. James Rubin writes of the two works:

“The Olympia is often compared to Cabanel’s Birth of Venus, for the latter is a far more sexually appealing work, despite its mythological guise… It is evident Manet’s demythologizing of the female nude was foremost a timely reminder of modern realities. The majority of critics attacked the painting with unmitigated disgust…: “What is this odalisque with the yellow belly, ignoble model dredged up from who knows where?” [And] “The painter’s attitude is of inconceivable vulgarity.”

(Rubin, James H. (1999), Impressionism, London: Phaidon Press Limited 67 - 68)The dialectics of Olympia and the Venus/Aphrodite binary

What shocked contemporary audiences was not Olympia's nudity, nor the presence of her fully clothed maid, but her confrontational gaze and a number of details identifying her as a demi-mondaine or prostitute. These include the orchid in her hair, her bracelet, pearl earrings and the oriental shawl on which she lies, symbols of wealth and sensuality. The black ribbon around her neck, in stark contrast with her pale flesh, and her cast-off slipper underline the voluptuous atmosphere. "Olympia" was a name associated with prostitutes in 1860s Paris.

The Venus of Urbino

Manet's Olympia painting is modelled after Titian's Venus of Urbino (c. 1534).

Whereas the left hand of Titian's Venus is curled and appears to entice, Olympia's left hand appears to block, which has been interpreted as symbolic of her role as a prostitute, granting or restricting access to her body in return for payment. Manet replaced the little dog (symbol of fidelity) in Titian's painting with a black cat, a creature associated with nocturnal promiscuity.

The aroused posture of the cat was provocative; in French, chatte (pussy) is slang for female genitalia.

Olympia disdainfully ignores the flowers presented to her by her servant, probably a gift from a client. Is she is looking in the direction of the door, as a client intrudes, barging in unannounced?

Unlike the smooth idealized nude of Alexandre Cabanel's La naissance de Vénus, also painted in 1863, Olympia is a real woman whose nakedness is emphasised by the harsh lighting. The canvas is larger than usual for this genre-style painting. Most paintings that were this size depicted historical or mythological events, so the size of the work, among other factors, caused surprise. Olympia is fairly thin by the artistic standards of the time and her relatively undeveloped body is more girlish than womanly. Charles Baudelaire thought this thinness was more indecent than fatness.The model for Olympia, Victorine Meurent, would have been recognised by viewers of the painting because she was well known in Paris circles. She started modelling when she was sixteen years old and she also was an accomplished painter in her own right. Some of her paintings were exhibited in the Paris Salon. The familiarity with the identity of the model was a major reason this painting was considered shocking to viewers. A well known woman currently living in modern-day Paris could not simultaneously represent a historical or mythological woman.Then there's Olympia's maid! A binary pairing?

The figure of the maid in the painting, modelled by a woman named Laure, has become a topic of discussion among contemporary scholars.

As T. J. Clark recounts of a friend's disbelief in the revised 1990 version of The Painting of Modern Life: "you've written about the white woman on the bed for fifty pages and more, and hardly mentioned the black woman alongside her."

Olympia was created 15 years after slavery had been abolished in France and its empire, but negative stereotypes of black people persisted among some elements of French society. In some cases, the white prostitute in the painting was described using racially charged language.

It was not for following an artistic convention that Manet included Laure but to create an ideological binary between black and white, good and bad, clean and dirty and so on.

When paired with a lighter skin tone, the Black female model stands in as signifier to all of the racial stereotypes of the West.

"Olympia's Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity"

This link is to an essay by Lorraine O'Grady, an American artist, writer, translator, and critic, originally published in 1992 in the book, New Feminist Criticism: Art, Identity, Action. The first part of the essay was published in Afterimage 20 (Summer 1992). Widely referenced in scholarly works, it is a cultural critique of the representation of Black female bodies, and the reclamation of the body as a site of black female subjectivity, and the West's construction of not-white women as not-to-be-seen.

O’Grady uses the painting Olympia by Édouard Manet as an example of Eurocentrism and its manifestation in both historical fact and in imaginative fiction. She begins:

The female body in the West is not a unitary sign. Rather, like a coin, it has an obverse and a reverse: on the one side, it is white; on the other, non-white or, prototypically, black. The two bodies cannot be separated, nor can one body be understood in isolation from the other in the West's metaphoric construction of "woman." White is what woman is; not-white (and the stereotypes not-white gathers in) is what she had better not be. Even in an allegedly postmodern era, the not-white woman as well as the not-white man are symbolically and even theoretically excluded from sexual difference. Their function continues to be, by their chiaroscuro, to cast the difference of white men and white women into sharper relief.

She continues, asking . . .

How could they/we not be affected by that lingering structure of invisibility, enacted in the myriad codicils of daily life and still enforced by the images of both popular and high culture? How not get the message of what Judith Wilson calls "the legions of black servants who loom in the shadows of European and European-American aristocratic portraiture," of whom Laura, the professional model that Edouard Manet used for Olympia's maid, is in an odd way only the most famous example? Forget "tonal contrast." We know what she is meant for: she is Jezebel and Mammy, prostitute and female eunuch, the two-in-one. When we're through with her inexhaustibly comforting breast, we can use her ceaselessly open cunt. And best of all, she is not a real person, only a robotic servant who is not permitted to make us feel guilty, to accuse us as does the slave in Toni Morrison's Beloved (1987). After she escapes from the room where she was imprisoned by a father and son, that outraged woman says: "You couldn't think up what them two done to me." Olympia's maid, like all the other "peripheral Negroes," is a robot conveniently made to disappear into the background drapery.To repeat: castrata and whore, not madonna and whore. Laura's place is outside what can be conceived of as woman. She is the chaos that must be excised, and it is her excision that stabilizes the West's construct of the female body, for the "femininity" of the white female body is ensured by assigning the not-white to a chaos safely removed from sight. Thus only the white body remains as the object of a voyeuristic, fetishizing male gaze. The not-white body has been made opaque by a blank stare, misperceived in the nether regions of TV.

"And here is now another example"

The Arcades Project

For Walter Benjamin, the philosopher, cultural critic and essayist (already mentioned re: aestheticisation of politics), the phenomenon of "Paris" had a particular importance in his thinking. In his major work, The Arcades Project, begun in 1927, but never completed (and in a way this was always to be so, given the use of his fragmentary style in presenting thoughts and questions), was about the rise of modern European urban culture, and Paris becomes important, not just as the capital city of France but, as evidenced in these two Exposés:

"Paris, the Capital of the Nineteenth Century" (1935)

"Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century" (1939)

An exposé being something, whether a film, other various media or a piece of writing, which reveals the truth about a situation or person, especially something involving shocking facts. According to the Wikipedia article on the subject of Benjamin's project:

Parisian arcades began to be constructed around the beginning of the nineteenth century and were sometimes destroyed as a result of Baron Haussmann's renovation of Paris during the Second French Empire (ca. 1850–1870). Benjamin linked them to the city's distinctive street life and saw them as providing one of the habitats of the flâneur (i.e., a person strolling in a locale to experience it).

Benjamin first mentioned the Arcades Project in a 1927 letter to his friend Gershom Scholem, describing it as his attempt to use collage techniques in literature. Initially, Benjamin saw the Arcades as a small article he would finish within a few weeks.

However, Benjamin's vision of the Arcades Project grew increasingly ambitious in scope until he perceived it as representing his most important creative accomplishment. On several occasions Benjamin altered his overall scheme of the Arcades Project, due in part to the influence of Theodor Adorno, who gave Benjamin a stipend and who expected Benjamin to make the Arcades project more explicitly political and Marxist in its analysis.

It contains sections (what he terms convolutes) on Arcades, Fashion, Catacombs, iron constructions, exhibitions, advertising, Interior design, Baudelaire, The Streets of Paris, Panoramas and Dioramas, Mirrors, Painting, Modes of Lighting, Railroads, Charles Fourier, Marx, Photography, Mannequins, Social movements, Daumier's caricatures, Literary History, the Stock exchange, Lithography, and the Paris Commune.

In considering:

"French culture and the nation" . . .

. . . Re:LODE Radio sees this phenomenon as symmetrically mirrored in the type of narcissism of:

"American culture and the nation". . .

. . . And when it comes to the notion of;

"the nation",

. . . the follow up to the question that the French historian Ernest Renan (1823–1892) asked in his 1882 lecture:

Q. "What is a Nation?" ("Qu'est-ce qu'une nation?")

includes the idea that a nation is;

"a daily referendum",

and that nations are based as much on;

"what the people jointly forget, as what they remember,"

and this observation is frequently quoted in historical discussions concerning nationalism and national identity.

Revolution on the streets! The Paris Commune - what is remembered and what is NOT!

This painting by Manet of the aftermath of the Haussmannisation of Paris with the Road-menders in the Rue Mossnier (1878) belies the trauma of the barricades that took place seven years earlier during the Paris Commune of 1871.

The Bloody Week

In 1871 the enemy of the French state was not the Prussian military ensconced in the Palace of Versailles (where, and when, the nation of a unified German Empire was proclaimed), for the bourgeoisie, for the conservative political class, the enemy was the proletarian working class citizens of Paris who refused to surrender, were later summarily executed in the thousands (estimates of 20,000 fatalities have been revised down to half that number in recent calculations) by the French army in the streets of Paris and the executions that took place in the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Map illustrating war between Paris Commune and National government

Benjamin's take on:

E. Haussmann, or the Barricades

I venerate the Beautiful, the Good, and all things great; Beautiful nature, on which great art rests -

How it enchants the ear and charms the eye!

I love spring in blossom: women and roses.Baron Haussmann, Confession d'un lion devenu vieux!Haussmann's activity is incorporated into Napoleonic imperialism, which favors investment capital. In Paris, speculation is at its height. Haussmann's expropriations give rise to speculation that borders on fraud. The rulings of the Court of Cassation, which are inspired by the bourgeois and Orleanist opposition, increase the financial risks of Haussmannization. Haussmann tries to shore up his dictatorship by placing Paris under an emergency regime. In 1864, in a speech before the National Assembly, he vents his hatred of the rootless urban population. This population grows ever larger as a result of his projects. Rising rents drive the proletariat into the suburbs. The quartiers of Paris in this way lose their distinctive physiognomy. The "red belt" forms. Haussmann gave himself the title of "demolition artist." He believed he had a vocation for his work, and emphasizes this in his memoirs. The central marketplace passes for Haussmann's most successful construction - and this is an interesting symptom. It has been said of the Île de la Cité, the cradle of the city, that in the wake of Haussmann only one church, one public building, and one barracks remained. Hugo and Merimee suggest how much the transformations made by Haussmann appear to Parisians as a monument of Napoleonic despotism. The inhabitants of the city no longer feel at home there; they start to become conscious of the inhuman character of the metropolis. Maxime Du Camp's monumental work Paris owes its existence to this dawning awareness. The etchings of Meryon (around 1850) constitute the death mask of old Paris.The true goal of Haussmann's projects was to secure the city against civil war. He wanted to make the erection of barricades in the streets of Paris impossible for all time. With the same end in mind, Louis Philippe had already introduced wooden paving. Nevertheless, barricades had played a considerable role in the February Revolution. Engels studied the tactics of barricade fighting. Haussmann seeks to forestall such combat in two ways. Widening the streets will make the erection of barricades impossible, and new streets will connect the barracks in straight lines with the workers' districts. Contemporaries christened the operation "strategic embellishment."

Civil War!

For Manet his 1878 picture of road menders may have contained echoes of his earlier prints titled Civil War (Guerre Civile) 1871–73, published 1874. After serving in the National Guard during the Siege of Paris, Manet remained outside the city for most of the Commune but returned to witness the atrocities of its violent suppression in late May 1871. According to his friend Théodore Duret, he based this lithograph on a sketch made from life near the Madeleine Church, the site of one of the first massacres of Communards by Versailles government troops. The dead National Guardsman lying beside the barricade stands for one of many, while the pinstriped pant legs in the right corner refer to additional civilian casualties.

Manet’s animated use of the lithographic medium, which included employing the side of the crayon for broad strokes, as well as scratching into the greasy black marks, suggests that the dust has barely settled on this scene. The role of Manet, the "flâneur", as a witness to state led atrocities upon citizens, in revolt, and revolutionary, contrasts with the artist who possessed a lifelong interest in the subject of leisure, entertainment, and the distractions of modern life.

The flâneur is a French noun referring to a person, literally meaning "stroller", "lounger", "saunterer", or "loafer", but with some nuanced additional meanings and as a loanword in English. Flânerie is the act of strolling, with all of its accompanying associations. A near-synonym of the noun is boulevardier. Traditionally depicted as male, a flâneur is an ambivalent figure of urban affluence and modernity, representing the ability to wander detached from society with no other purpose than to be an acute observer of industrialized, contemporary life.

The flâneur was, first of all, a literary type from 19th-century France, essential to any picture of the streets of Paris. The word carried a set of rich associations: the man of leisure, the idler, the urban explorer, the connoisseur of the street. It was Walter Benjamin, drawing on the poetry of Charles Baudelaire, who made this figure the object of scholarly interest in the 20th century, as an emblematic archetype of urban, modern (even modernist) experience. Following Benjamin, the flâneur has become an important symbol for scholars, artists, and writers.

Manet's interest in all aspects of modern life, the various manifestations of cultural, economic and political exchanges, be they characterised by the exchange of bullets, or sex for money, along with champagne and red triangles on bottled beer, ends in this work.

The "pretty girl", is she a sex worker on the side?

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (Un bar aux Folies Bergère)

This is Édouard Manet's last major work. It was painted in 1882 and exhibited at the Paris Salon of that year. It depicts a scene in the Folies Bergère nightclub in Paris.

No dust in this scene of new building developments in Paris!

This painting of 1877 by Gustave Caillebotte, best known for his paintings of urban Paris, is titled Paris Street; Rainy Day (Rue de Paris; temps de pluie, also known as La Place de l'Europe, temps de pluie) and shows new paving glistening in the rain. Any sense of a potential weaponising of the architecture, and the street itself, has been removed and replaced by the denizens of a bourgeoisie surveying entirely new and unthreatening prospects.

She wears a hat, veil, diamond earring, demure brown dress, and a fur lined coat, described in 1877 as "modern – or should I say, the latest fashion". The man wears a moustache, topcoat, frock coat, top hat, bow tie, starched white shirt, buttoned waistcoat and an open long coat with collar turned up. They are unambiguously middle class. Some working class figures may be seen in the background; a maid in a doorway, the decorator carrying a ladder, cut-off by the umbrella above him. Caillebotte juxtaposes the figures and the perspective in a playful manner, with one man appearing to jump from the wheel of a carriage; another pair of legs appear below the rim of an umbrella.This painting is almost unique among his works for its particularly flat colours and photo-realistic effect, which give the painting its distinctive and modern look.

The Paris Commune remembered and/or a memory erased and/or conveniently forgotten?

The echoes of this cultural and political trauma cut through those efforts of denial, or forgetting, for those on the "Left" the Commune is both a lesson and an emblem. Karine Varley, in her paper: Memories Not Yet Formed: Commemorating the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, explores this complex situation in the context of attempts to the memorialising the Franco Prussian War inevitably evoking memories of the Commune that required control management, and suppression. However, such control management of history and memory is made somewhat more difficult when an iconic Parisian landmark is the site of the burial of that history and the erasure of a collective memory.

Q. And what is this iconic landmark?

A. Montmartre, including the Basilica of the Sacré-CœurIn this video France 24 takes its audience on a tour of the history of Montmartre that includes the iconic structure that overlooks Paris, the Basilica of the Sacré-Cœur, that, in its purpose, and in its construction, was and is, sheer counter-revolutionary propaganda.

A tourist destination and . . .

The Paris Commune was the main insurrectionary commune of France in 1870-1871, based on direct democracy and established in Paris from 18 March to 28 May 1871.During the Franco-Prussian War, Paris had been defended by the National Guard, where working class radicalism grew among soldiers.Everyday life for Parisians became increasingly difficult during the siege. In December temperatures dropped to −15 °C (5 °F), and the Seine froze for three weeks. Parisians suffered shortages of food, firewood, coal and medicine. The city was almost completely dark at night. The only communication with the outside world was by balloon, carrier pigeon, or letters packed in iron balls floated down the Seine. Rumours and conspiracy theories abounded. Because supplies of ordinary food ran out, starving denizens ate most of the city zoo's animals, then resorted to feeding on rats.By early January 1871, Bismarck and the Germans themselves were tired of the prolonged siege. They installed seventy-two 120- and 150-mm artillery pieces in the forts around Paris and on 5 January began to bombard the city day and night. Between 300 and 600 shells hit the centre of the city every day.Between 11 and 19 January 1871, the French armies had been defeated on four fronts and Paris was facing a famine. General Trochu received reports from the prefect of Paris that agitation against the government and military leaders was increasing in the political clubs and in the National Guard of the working-class neighbourhoods of Belleville, La Chapelle, Montmartre, and Gros-Caillou.At midday on 22 January, three or four hundred National Guards and members of radical groups — mostly Blanquists — gathered outside the Hôtel de Ville. A battalion of Gardes Mobiles from Brittany was inside the building to defend it in case of an assault. The demonstrators presented their demands that the military be placed under civil control, and that there be an immediate election of a commune. The atmosphere was tense, and in the middle of the afternoon, gunfire broke out between the two sides; each side blamed the other for firing first. Six demonstrators were killed, and the army cleared the square. The government quickly banned two publications, Le Reveil of Delescluze and Le Combat of Pyat, and arrested 83 revolutionaries.At the same time as the demonstration in Paris, the leaders of the Government of National Defence in Bordeaux had concluded that the war could not continue. With Paris starving, and Gambetta's provincial armies reeling from one disaster after another, French foreign minister Favre went to Versailles on 24 January to discuss peace terms with Bismarck.

Bismarck agreed to end the siege and allow food convoys to immediately enter Paris (including trains carrying millions of German army rations), on condition that the Government of National Defence surrender several key fortresses outside Paris to the Prussians. Without the forts, the French Army would no longer be able to defend Paris.Although public opinion in Paris was strongly against any form of surrender or concession to the Prussians, the Government realised that it could not hold the city for much longer, and that Gambetta's provincial armies would probably never break through to relieve Paris. President Trochu resigned on 25 January and was replaced by Favre, who signed the surrender two days later at Versailles, with the armistice coming into effect at midnight.

Following the Siege of Paris and the military defeat of French forces by the Prussian war machine, on 26 January 1871 the Government of National Defence based in Paris negotiated an armistice with the Prussians with special conditions for Paris. The city would not be occupied by the Germans. Regular soldiers would give up their arms, but would not be taken into captivity. Paris would pay an indemnity of 200 million francs. At Jules Favre's request, Bismarck agreed not to disarm the National Guard, so that order could be maintained in the city.

The national government in Bordeaux held national elections on 8 February. Most electors in France were rural, Catholic and conservative, and this was reflected in the results; of the 645 deputies assembled in Bordeaux on February, about 400 favoured a constitutional monarchy under either Henri, Count of Chambord (grandson of Charles X) or Prince Philippe, Count of Paris (grandson of Louis Philippe).Of the 200 republicans in the new parliament, 80 were former Orléanists (Philippe's supporters) and moderately conservative. They were led by Adolphe Thiers, who was elected in 26 departments, the most of any candidate. There were an equal number of more radical republicans, including Jules Favre and Jules Ferry, who wanted a republic without a monarch, and who felt that signing the peace treaty was unavoidable. Finally, on the extreme left, there were the radical republicans and socialists, a group that included Louis Blanc, Léon Gambetta and Georges Clemenceau. This group was dominant in Paris, where they won 37 of the 42 seats.On 17 February the new Parliament elected the 74-year-old Thiers as chief executive of the Third Republic. He was considered to be the candidate most likely to bring peace and to restore order. Long an opponent of the Prussian war, Thiers persuaded Parliament that peace was necessary. He travelled to Versailles, where Bismarck and the German Emperor were waiting, and on 24 February the armistice was signed.

A Battery in the Montmartre Hills.

At the end of the war 400 obsolete muzzle-loading bronze cannons . . .. . . paid for by the Paris public via a subscription, remained in the city. The new Central Committee of the National Guard, now dominated by radicals, decided to put the cannons in parks in the working-class neighborhoods of Belleville, Buttes-Chaumont and Montmartre, to keep them away from the regular army and to defend the city against any attack by the national government. Thiers was equally determined to bring the cannons under national-government control.Clemenceau, a friend of several revolutionaries, tried to negotiate a compromise; some cannons would remain in Paris and the rest go to the army. However, neither Thiers nor the National Assembly accepted his proposals. The chief executive wanted to restore order and national authority in Paris as quickly as possible, and the cannons became a symbol of that authority. The Assembly also refused to prolong the moratorium on debt collections imposed during the war; and suspended two radical newspapers, Le Cri du Peuple of Jules Valles and Le Mot d'Ordre of Henri Rochefort, which further inflamed Parisian radical opinion. Thiers also decided to move the National Assembly and government from Bordeaux to Versailles, rather than to Paris, to be farther away from the pressure of demonstrations, which further enraged the National Guard and the radical political clubs.On 17 March 1871, there was a meeting of Thiers and his cabinet, who were joined by Paris mayor Jules Ferry, National Guard commander General D'Aurelle de Paladines and General Joseph Vinoy, commander of the regular army units in Paris. Thiers announced a plan to send the army the next day to take charge of the cannons. The plan was initially opposed by War Minister Adolphe Le Flô, D'Aurelle de Paladines, and Vinoy, who argued that the move was premature, because the army had too few soldiers, was undisciplined and demoralized, and that many units had become politicized and were unreliable. Vinoy urged that they wait until Germany had released the French prisoners of war, and the army returned to full strength. Thiers insisted that the planned operation must go ahead as quickly as possible, to have the element of surprise. If the seizure of the cannon was not successful, the government would withdraw from the centre of Paris, build up its forces, and then attack with overwhelming force, as they had done during the uprising of June 1848. The Council accepted his decision, and Vinoy gave orders for the operation to begin the next day.Early in the morning of 18 March, two brigades of soldiers climbed the butte of Montmartre, where the largest collection of cannons, 170 in number, were located. A small group of revolutionary national guardsmen were already there, and there was a brief confrontation between the brigade led by General Claude Lecomte, and the National Guard; one guardsman, named Turpin, was shot, later dying. Word of the shooting spread quickly, and members of the National Guard from all over the neighbourhood, along with others including Clemenceau, hurried to the site to confront the soldiers.While the Army had succeeded in securing the cannons at Belleville and Buttes-Chaumont and other strategic points, at Montmartre a crowd gathered and continued to grow, and the situation grew increasingly tense. The horses that were needed to take the cannon away did not arrive, and the army units were immobilized. As the soldiers were surrounded, they began to break ranks and join the crowd. General Lecomte tried to withdraw, and then ordered his soldiers to load their weapons and fix bayonets. He thrice ordered them to fire, but the soldiers refused. Some of the officers were disarmed and taken to the city hall of Montmartre, under the protection of Clemenceau. General Lecomte and his staff officers were seized by the guardsmen and his mutinous soldiers and taken to the local headquarters of the National Guard at the ballroom of the Chateau-Rouge. The officers were pelted with rocks, struck, threatened, and insulted by the crowd. In the middle of the afternoon, Lecomte and the other officers were taken to 6 Rue des Rosiers by members of a group calling themselves The Committee of Vigilance of the 18th arrondissement, who demanded that they be tried and executed.At 5:00 in the afternoon, the National Guard had captured another important prisoner: General Jacques Leon Clément-Thomas. An ardent republican and fierce disciplinarian, he had helped suppress the armed uprising of June 1848 against the Second Republic. Because of his republican beliefs, he had been arrested by Napoleon III and exiled, and had only returned to France after the downfall of the Empire. He was particularly hated by the national guardsmen of Montmartre and Belleville because of the severe discipline he imposed during the siege of Paris. Earlier that day, dressed in civilian clothes, he had been trying to find out what was going on, when he was recognized by a soldier and arrested, and brought to the building at Rue des Rosiers. At about 5:30 on 18 March, the angry crowd of national guardsmen and deserters from Lecomte's regiment at Rue des Rosiers seized Clément-Thomas, beat him with rifle butts, pushed him into the garden, and shot him repeatedly. A few minutes later, they did the same to General Lecomte. Doctor Guyon, who examined the bodies shortly afterwards, found forty bullets in Clément-Thomas's body and nine in Lecomte's back. By late morning, the operation to recapture the cannons had failed, and crowds and barricades were appearing in all the working-class neighborhoods of Paris. General Vinoy ordered the army to pull back to the Seine, and Thiers began to organise a withdrawal to Versailles, where he could gather enough troops to take back Paris.On the afternoon of 18 March, following the government's failed attempt to seize the cannons at Montmartre, the Central Committee of the National Guard ordered the three battalions to seize the Hôtel de Ville, where they believed the government was located. They were not aware that Thiers, the government, and the military commanders were at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where the gates were open and there were few guards. They were also unaware that Marshal Patrice MacMahon, the future commander of the forces against the Commune, had just arrived at his home in Paris, having just been released from imprisonment in Germany. As soon as he heard the news of the uprising, he made his way to the railway station, where national guardsmen were already stopping and checking the identity of departing passengers. A sympathetic station manager hid him in his office and helped him board a train, and he escaped the city. While he was at the railway station, national guardsmen sent by the Central Committee arrived at his house looking for him.On the advice of General Vinoy, Thiers ordered the evacuation to Versailles of all the regular forces in Paris, some 40,000 soldiers, including those in the fortresses around the city; the regrouping of all the army units in Versailles; and the departure of all government ministries from the city.Late on 18 March, when they learned that the regular army was leaving Paris, units of the National Guard moved quickly to take control of the city. The first to take action were the followers of Blanqui, who went quickly to the Latin Quarter and took charge of the gunpowder stored in the Pantheon, and to the Orleans railway station. Four battalions crossed the Seine and captured the prefecture of police, while other units occupied the former headquarters of the National Guard at the Place Vendôme, as well as the Ministry of Justice. That night, the National Guard occupied the offices vacated by the government; they quickly took over the Ministries of Finance, the Interior, and War. At eight in the morning the next day, the Central Committee was meeting in the Hôtel de Ville. By the end of the day, 20,000 national guardsmen camped in triumph in the square in front of the Hôtel de Ville, with several dozen cannons.

A red flag was hoisted over the building.The events that instigated the revolutionary process on the hills of Montmartre are dramatised in the Soviet Russian 1929 silent historical film The New Babylon, written and directed by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg.

The film deals with the 1871 Paris Commune and the events leading to it, and follows the encounter and tragic fate of two lovers separated by the barricades of the Commune.Leonid Trauberg, later admitted, the film as it stands is a little difficult to follow. Its subtitle Assault on the Heavens: Episodes from the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, 1870-71 makes it fairly obvious that it is a principally a political film, and not a love story. Some background knowledge of the Paris Commune is needed to understand what's going on around the two lovers. As Fiona Ford remarks, "Both New Babylon and Eisenstein's October are episodic in structure and require an intimate knowledge of their relevant historical periods (the Paris Commune of 1871 in the case of New Babylon) to better appreciate the directors' intentions and often simply to follow the diegesis."

With Eccentrism there's . . .

The New Babylon was staged with members of the "Factory of the Eccentric Actor" (FEKS) - an avant-garde artists' association founded by Kozintsev and Trauberg in 1922 that sought to create new paths in the performing arts. FEKS first began as a theater group, but in the following years, many of its members shaped the Russian-Soviet film history when working as actors, outfitters, and cinematographers. They wanted to get away from the naturalism and empathy aesthetics of bourgeois art, and saw Eccentrism (as laid out in Trauberg's Eccentric Manifesto) as a new direction within the avant-garde that sought to find a place between Futurism, Surrealism and Dadaist Constructivism.

The Russian premiere of The New Babylon took place on 18 March 1929 in Leningrad, the anniversary of the events that instigated the beginning of the Paris Commune.

Re:LODE Radio considers the significance of the fact that The New Babylon was one amongst a number of films that were included in a "jumble of footage from feature films juxtaposed with still photographs, industrial films, early 1970s glossy 'lifestyle' TV ads, and news footage of unrest in the streets ", a montage that became a 1974 film La Société du Spectacle (Society of the Spectacle) by the Situationist Guy Debord, and based on his 1967 book of the same name. It was Debord's first feature-length film. It uses found footage and détournement in a radical Marxist critique of mass marketing and its role in the alienation of modern society. Other feature film footage included excerpts from The Battleship Potemkin, October, Chapaev, The Shanghai Gesture, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Rio Grande, They Died with Their Boots On, Johnny Guitar, and Mr. Arkadin.

The title The New Babylon refers to a fictional twin of the Parisian department store (magazin):

Le Bon Marché

See more: "clickbait" -On stage & on display in Bon Marché & the brothels of Paris

Women participants!

This visually striking poster for The New Babylon, foregrounds the image of a working class woman in the active role of one of the main protagonists in this revolution, meanwhile capitalist businessmen drink their wine and cavort with their female playthings. The central role of "Louise", a worker at the department store, the New Babylon, stresses the equal importance of women in this radical insurrection. The film directors, Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg include many scenes with women as workers, in both the industrial and domestic spheres, as active and activist, instigating a collective response to this moment of crisis. This is evident in the treatment of the events on the hills of Montmartre that sparked the insurgency and as depicted in the film, and contributes to the received idea in images of the Commune, of the role of the unruly women of Paris.

Les Pétroleuses

NOT this film The Legend of Frenchie King (French: Les Pétroleuses).

The 1971 French, Spanish, Italian and British international co-production western comedy film directed by Christian-Jaque and starring Claudia Cardinale and Brigitte Bardot.

These Pétroleuses . . .

. . . arrested in Versailles in the aftermath of the failed revolution!

A significant material consequence of the storming of the Commune by the Versaillais, as the French forces were called, included the destruction by fire of many buildings and neighbourhoods, including the Fields of Elysium (Champs-Élysées) . . .

. . . the Hôtel de Ville, Paris, and . . .

. . . most traumatically for the French Bourgeoisie, . . .

. . . the destruction by fire of the Tuileries Royal Palace.

Pétroleuses were, according to popular rumours at the time, female supporters of the Paris Commune, accused of burning down much of Paris during the last days of the Commune in May 1871. During May, when Paris was being recaptured by loyalist Versaillais troops, rumours circulated that working class women were committing arson against private property and public buildings, using bottles full of petroleum or paraffin (similar to modern-day Molotov cocktails) which they threw into cellar windows, in a deliberate act of spite against the government.

Many of the Parisian buildings, including the Hôtel de Ville, the Tuileries Palace, the Palais de Justice and many other government buildings were in fact set afire by the soldiers of the Commune during the last days of the Commune, prompting the press and Parisian public opinion to blame the pétroleuses.

However, of the thousands of suspected pro-Communard women tried in Versailles after the Commune ended, only a handful were convicted of any crimes, and their convictions were based on activity such as shooting at loyalist troops. Official trial records show that no women were ever convicted of arson, and that accusations of the crime were quickly shown to have no basis. Nevertheless, although few of the women brought to trial were executed, many working-class women were killed on site by Versaillais troops. Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray reported in his memoirs:

“Every woman who was badly dressed, or carrying a milk-can, a pail, an empty bottle, was pointed out as a petroleuse, her clothes torn to tatters, she was pushed against the nearest wall, and killed with revolver-shots"The history of the Paris Commune by Maxime Du Camp, written in the 1870s, and more recent research by historians of the Paris Commune, including Robert Tombs and Gay Gullickson, concluded that there were no incidents of deliberate arson by pétroleuses.

There is some debate on this, as the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune approaches, and some now believe that the buildings destroyed at the end of the Commune were not burned down by pétroleuses but were largely caused by Versailles cannon fire. The Hôtel de Ville, the Palais de Justice, the Tuileries Palace and other government buildings and symbols of authority were burned by Commune forces as they retreated. Other fires were started by Communard forces, as a tactic to push back Versailles' troops if ground was lost. Some buildings along the Rue de Rivoli were burned down during street-fighting between Communards and Versaillais troops. Gullickson suggests that the myth of the pétroleuses was part of a propaganda campaign by Versaillais politicians, who portrayed Parisian women in the Commune as unnatural, destructive, and barbaric, giving loyalist forces a moral victory over the "unnatural" Communards.Kate Rees, writing in the TLS on Peter Brooks’s Flaubert in the Ruins of Paris, writes that: