Homo sapiens (wise)?

“Human” comes to us, via French humain, from the Latin humanus, which is related to homo as in sapiens (wise). In English, “human” and “humane” used to be the same word, as though it were a particular quality of human beings to act with kindness; the modern distinction was not made until the 18th century.

Out of Africa

The LODE Zone Line does not traverse the continent of Africa, but the LODE Zone Line crosses many histories that are connected to this vast continent at the centre of human kind's origins. There is a famous ancient Latin adage (credited to sages from Aristotle to Pliny to Erasmus) Ex Africa semper aliquid novi, which translates as “Out of Africa, always something new.”

According to the Wikipedia article on human evolution Homo sapiens (the adjective sapiens is Latin for "wise" or "intelligent") emerged in Africa around 300,000 years ago, likely derived from Homo heidelbergensis or a related lineage. In September 2019, scientists reported the computerized determination, based on 260 CT scans, of a virtual skull shape of the last common human ancestor to modern humans/H. sapiens, representative of the earliest modern humans, and suggested that modern humans arose between 260,000 and 350,000 years ago through a merging of populations in East and South Africa.

Between 400,000 years ago and the second interglacial period in the Middle Pleistocene, around 250,000 years ago, the trend in intra-cranial volume expansion and the elaboration of stone tool technologies developed, providing evidence for a transition from H. erectus to H. sapiens. The direct evidence suggests there was a migration of H. erectus out of Africa, then a further speciation of H. sapiens from H. erectus in Africa. A subsequent migration (both within and out of Africa) eventually replaced the earlier dispersed H. erectus. This migration and origin theory is usually referred to as the "recent single-origin hypothesis" or "out of Africa" theory. H. sapiens interbred with archaic humans both in Africa and in Eurasia, in Eurasia notably with Neanderthals and Denisovans.

The map below charts the migration of modern humans out of Africa, based on mitochondrial DNA. Coloured rings indicate thousand years before present.

Out of Africa and a colonial perspective

Re:LODE Radio is prompted to reference the notion of "Out of Africa" primarily by an Opinion piece in the Guardian that, in turn, references a cinematic sequence from the film Out of Africa.

The Opinion piece referenced is by Laura Spinney, a science journalist and author of Pale Rider: the Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World. Laura Spinney's piece was published in the print edition of the Guardian Tuesday 22 December 2020 with the headline:

The colonialist thinking that skews our view of deforestation

Re:LODE Radio acknowledges that it is this notion of "colonialist thinking" that, as an "organising idea", shapes some of the thinking running through this post.

The photo used in the Guardian webpage is of Bioko island, Equatorial Guinea. ‘In much of west Africa, forest cover actually increased over the course of the 20th century.’

Laura Spinney writes:

To prevent future pandemics, we must stop deforestation and end the illegal wildlife trade. Do you agree? Of course you do, because what’s not to like? The buck stops with the evil other. The question is, will doing those things solve the problem? And the answer is, probably not. They will help, but there’s another, potentially bigger problem closer to home: the global north’s use of natural resources, especially its reliance on livestock.

The story that epidemics are punishment for upsetting the natural order of things is not new. But it’s a peculiarly modern, postcolonial twist on it to imagine that the source of that upset is somewhere far away from most of us – to wit, the parts of the world that were forested, until recently, and that conveniently coincide with the poorer bits. And it turns out that this narrative may be interfering with our attempts to protect ourselves from novel diseases, as well as with efforts to tackle climate change and the erosion of biodiversity.As the French environmental historian Guillaume Blanc argues in a new book that has yet to be translated into English, L’invention du colonialisme vert (The Invention of Green Colonialism), the idea that Africa was once covered by a vast, primary forest is a myth invented by colonialists in the early 20th century. Over a period of several million years, the continent’s tree cover waxed and waned as the climate warmed and cooled. After humans came along, they cleared some trees and planted others, such that by the time Denys Finch Hatton took Karen Blixen for a spin in his Gipsy Moth – a scene immortalised in Sydney Pollack’s 1985 film Out of Africa – the Kenyan landscapes they soared over were thoroughly human-sculpted.

Starting in the 1930s, colonialists created national parks to protect the forests from the locals who were supposedly destroying them as their populations grew. But the hypocrisy is double-barrelled, because by then it was the colonialists who were responsible for large-scale destruction. Between 1850 and 1920, across Africa and Asia, Europeans and their descendants cut down 95m hectares of forest to make way for their farms – between four and five times more than was destroyed in the previous century.The myth of the vanished forest persists. As the American environmental historian James McCann has shown, the former US vice-president Al Gore’s laudable and Nobel prize-winning fight to alert the world to climate change – in part through his 1992 book Earth in the Balance – borrowed spurious statistics according to which Ethiopia’s forest cover shrank from 40% in the 1950s to 1% in the 1990s (Ethiopia was never colonised). The 40% figure is based on breezy guesstimates put out by Europeans in the 1960s; no systematic study of that country’s forests has ever been conducted. In much of west Africa, meanwhile, the British anthropologists Melissa Leach and James Fairhead have shown that forest cover actually increased over the course of the 20th century. In Asia, too, research has cast doubt on the assumed link between local population growth and deforestation.So powerful is the myth, we simply accept the inconsistencies that flow from it. The fact, for example, that the carbon footprint of a tourist from the global north visiting an African or Asian national park dwarfs that of a local farmer who travels on foot and uses no electricity. Though there is no evidence of major human-induced destruction of Africa’s flora and fauna until the arrival of colonialists, we have internalised their distinction between “good” and “bad” hunters. When Thomas Cholmondeley, scion of a well-known white settler family in Kenya, was convicted of the manslaughter in 2006 of Robert Njoya, many journalists observed that Britain’s colonial past had been on trial with him, but few questioned his description of himself as a sports hunter and conservationist, while Njoya, a black man, was a “poacher”.Conservation and over-exploitation of the world’s resources were born in the same time and place, Blanc argues – Europe during the Industrial Revolution – and have proceeded in parallel ever since. Both spring from Europeans’ search for Eden after they had destroyed it at home. And the myth of that other Eden has returned with a vengeance, now that we find ourselves in the midst of a pandemic.We know that greater intensity of human-animal contact is accelerating the emergence of new human diseases of animal origin, some of which have pandemic potential, and we know that in many cases – including coronaviruses – the virus reaches us from a wild bat or rodent (the natural reservoir) via a farmed animal (the intermediate host). We blame the wildlife trade – the bad hunters – and deforestation for increasing encounters between people and natural reservoirs, but say nothing about the bridge. The elephant – or rather the cow, camel or civet in the room – is livestock.Here self-delusion segues into cynicism, because industrial-scale farming businesses, many of which are located in the global north, know very well the risk they represent – that’s why they conduct surveillance of their flocks and herds for new pathogens. So far, they happen to be better at it in the US and Europe than in China. But all over the world, those businesses are pushing their smaller-scale counterparts closer to the forest. Sometimes they even push the small-scale farmers out of business and into the wildlife trade.Deforestation is real, in some places, but where it is happening the capital and the mindset driving it can often be traced back to the global north – as it could a century ago. It’s our rapacious consumption that is the problem – and that applies to climate change and biodiversity loss, too. The global south is well aware of this. That’s why it took 20 years from the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro for an international organisation to be created to address the biodiversity problem. North and south were wrangling over whose values should dominate the conservation agenda. It’s also why there is an ongoing struggle over ownership of the world’s genetic resources.Sometimes, as Blanc notes, the south makes the north’s hypocrisy work for it, as in the case of the African governments that treat national parks as cash cows. But nobody is fooled. From aid to conservation, the south knows to be wary of the white saviour complex, because of the ugly truths it hides.Finding solutions to our genuine problems is going to be fiendishly difficult, but the process has to start with a recognition that nature is one big interconnected skein, of which we in the global north form a part, and that we’re the ones currently pulling it out of shape. We’re not all white – and we can argue about where the global north begins and ends – but if a northerner is writing this, and citing another northerner called, appropriately, Monsieur Blanc, it’s because it’s our myth that’s making the world sick – and we should bust it.

Out of Africa is the title of the memoir by Danish author Karen Blixen, and inspired Sydney Pollack’s 1985 film. The book, first published in 1937, recounts events of the seventeen years when Blixen made her home in Kenya, then called British East Africa.

The cover design of the first edition is of a pristine natural state, an Eden, unsullied and devoid of a human presence. In subtle ways the romanticised version and vision of nature is essentially anti-human.

Hieronymous Bosch's version of the Millennium or what is now called the Garden of Earthy Delights, includes a surreal, prickly, active and fluid interface between:

human beings and "nature" . . .

. . . along with the complex interface between different people coming together.

A snapshot of colonial thinking . . .

The book is a lyric meditation on Blixen's life on her coffee plantation, as well as a tribute to some of the people who touched her life there. It provides a vivid snapshot of African colonial life in the last decades of the British Empire.

Karen Blixen moved to British East Africa in late 1913, at the age of 28, to marry her second cousin, the Swedish Baron Bror von Blixen-Finecke, and make a life in the British colony. The young Baron and Baroness bought farmland below the Ngong Hills about ten miles (16 km) southwest of Nairobi, which at the time was still shaking off its rough origins as a supply depot on the Uganda Railway.The Blixens had planned to raise dairy cattle, but Bror developed their farm as a coffee plantation instead. It was managed by Europeans, including, at the start, Karen's brother Thomas – but most of the labour was provided by “squatters.” This was the colonial term for local Kikuyu tribespeople who guaranteed the owners 180 days of labour in exchange for wages and the right to live and farm on the uncultivated lands which, in many cases, had simply been theirs before the British arrived and stole them.Much of Blixen's energy in Out of Africa is spent trying to capture for the reader the character of the Africans who lived on or near her farm, and the efforts of European colonists (herself included) to co-exist with them.Although she was unavoidably in the position of landholder, and wielded great power over her tenants, Blixen was known in her day for her respectful and admiring relationships with Africans – a connection that made her increasingly suspect among the other colonists as tensions grew between Europeans and Africans. “We were good friends,” she writes about her staff and workers. “I reconciled myself to the fact that while I should never quite know or understand them, they knew me through and through.”But Blixen does understand – and thoughtfully delineates – the differences between the culture of the Kikuyu who work her farm and who raise and trade their own sheep and cattle, and that of the Maasai, a volatile warrior culture of nomadic cattle-drovers who live on a designated tribal reservation south of the farm's property. Blixen also describes in some detail the lives of the Somali Muslims who emigrated south from Somaliland to work in Kenya, and a few members of the substantial Indian merchant minority which played a large role in the colony's early development.Her descriptions of Africans and their behaviour or customs sometimes employ some of the racial language of her time, deemed now to be abrasive, but her portraits are frank and accepting, and are generally free of perceptions of Africans as savages or simpletons. She transmits a sense of logic and dignity of ancient tribal customs. Some of those customs, such as the valuation of daughters based on the dowry they will bring at marriage, are perceived as ugly to Western eyes; Blixen's voice in describing these traditions is largely free of judgment.She was admired in return by many of her African employees and acquaintances, who saw her as a thoughtful and wise figure, and turned to her for the resolution of many disputes and conflicts.A "decent person", but shaped by an immanent colonialist perspective nonetheless . . .

. . . and a perspective that continues to be institutionalised to this day, and to such an extent that for those who "see" in this way (psychological projection), it's normal! The LODE project purpose, above all, is to enable the withdrawal of those distorted psychological projections people make onto a "wonderful world", that's sadly misshapen in our age of the capitalocene.

For example . . .

This video can be seen on YouTube and is one of many examples of the work undertaken by Playing For Change, a multimedia music project, co-founded in 2002 by American music engineer/producer Mark Johnson and film producer/philanthropist Whitney Kroenke. Playing For Change also created a separate non-profit organization called the Playing For Change Foundation, which builds music and art schools for children around the world.

Playing For Change was founded in 2002 by Mark Johnson and Whitney Kroenke. Producers Johnson and Enzo Buono traveled around the world to places including New Orleans, Barcelona, South Africa, India, Nepal, the Middle East and Ireland. Using mobile recording equipment, the duo recorded local musicians performing the same song, interpreted in their own style. Among the artists participating or openly involved in the project are Vusi Mahlasela, Louis Mhlanga, Clarence Bekker, David Guido Pietroni, Tal Ben Ari (Tula), Bono, Keb' Mo', David Broza, Manu Chao, Grandpa Elliott, Keith Richards, Toots Hibbert from Toots & the Maytals, Taj Mahal and Stephen Marley. This resulted in the documentary A Cinematic Discovery of Street Musicians that won the Audience Award at the Woodstock Film Festival in September 2008.

Mark Johnson was walking in Santa Monica, California, when he heard the voice of Roger Ridley (deceased in 2005) singing "Stand By Me"; it was this experience that sent Playing For Change on its mission to connect the world through music.

The founders of Playing For Change created the Playing For Change Foundation, a separate 501(c)3 nonprofit organisation.

In 2011, the Playing For Change Foundation established an annual Playing For Change Day. The goal of Playing For Change Day is to "unite a global community through the power of music to affect positive social change".In 2019, the Playing For Change Foundation was awarded the Polar Music Prize. The Polar Music Prize is a Swedish international award founded in 1989 by Stig Anderson, best known as the manager of the Swedish band ABBA, with a donation to the Royal Swedish Academy of Music. The award is annually given to one contemporary musician and one classical musician. In 2019 the classical music recipient was Anne-Sophie Mutter.

The text accompanying this video of What a Wonderful World (Louis Armstrong), Playing For Change Song, Around The World (20 Nov 2012), on YouTube explains:

Playing For Change is proud to present this video of the song "What A Wonderful World" featuring Grandpa Elliott with children's choirs across the globe. In these hard times, children and music bring us hope for a better future. Today we celebrate life and change the world one heart and one song at a time!!

This video was produced in partnership with Okaïdi children's clothing stores. Okaidi designed a special line of PFC T-Shirts to be sold in over 700 Okaïdi stores worldwide this holiday season. Okaïdi has committed 1 euro per T-Shirt sold to go to supporting the PFC Musicians and PFC Foundation's music education programs. We thank them for their generous support of the Playing For Change Movement!

Re:LODE Radio wonders:

Is this marketing? Framing economic activity with smiling children, black children, white children, brown children, human kind?

Or, a noble cause, problematised by a colonial mind/culture-set?

A video, a film, a photograph, in each of these forms of media we do not simply encounter a document of one kind of reality or another. Mediated images generated from the material of reality do not describe reality, they, in effect, substitute themselves for reality. This is our information environment, increasingly immersive, and that shapes our perception of the world and all its inhabitants, including human kind.

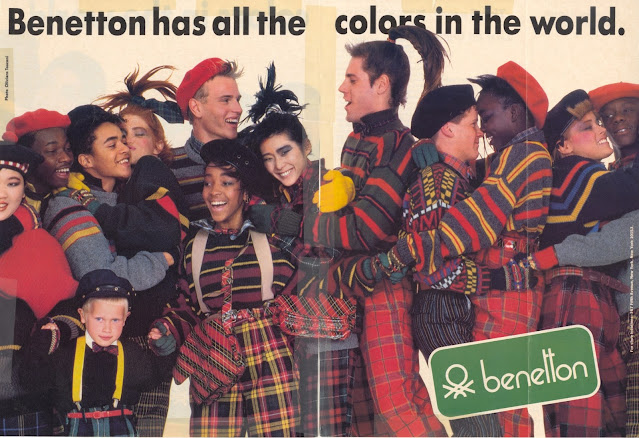

Take this advertisement for example, an image produced by the Italian global fashion brand Benetton. As Kate Collins says, writing for the blog of the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University (April 8 2019):These ads, like the one seen above that was featured in the magazine Mademoiselle in 1983, were part of a campaign called “All the Colors of the World.” With their messages of global harmony, these ads would take on dozens of different iterations in the next two decades. They became such a staple in Benetton’s marketing repertoire that in the 1990s, the expression “a Benetton ad” was sometimes used to refer to an image with a diverse group of people.

Q. Where did the template for this image come from?

A. From photography itself.

The message was in the medium. The medium was the message, and squaring the circle of difference and global harmony was immanent in the medium of photography itself. This potentiality was exemplified significantly in the 1955 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art New York, that was titled The Family of Man. This was an ambitious photography exhibition curated by Edward Steichen, the director of the Museum of Modern Art's (MoMA) Department of Photography. According to Steichen, the exhibition represented the "culmination of his career."

The Family of Man was first shown in 1955 from January 24 to May 8 at the New York MoMA, then toured, making stops in thirty-seven countries on six continents. More than 9 million people viewed the exhibit, which is still in excess of the largest audience for any photographic exhibition since. The tour schedule lasted for eight years and that assured these record-breaking audience numbers. Commenting on its appeal, Steichen said the people "looked at the pictures, and the people in the pictures looked back at them. They recognized each other."

The title of the exhibition was taken from a line in a Carl Sandburg poem, The Long Shadow of Lincoln: A Litany (1944):There is dust aliveWith dreams of the Republic,With dreams of the family of manFlung wide on a shrinking globe

The exhibition opened with an entrance archway papered with a blow-up of a crowd in London by Pat English framing Wyn Bullock's Chinese landscape of sunlight on water into which was inset an image of a truncated nude of a pregnant woman in an evocation of creation myths. Subjects then ranged in sequence from lovers, to childbirth, to household, and careers, then to death and on a topical portentous note, the hydrogen bomb.

Finally, full cycle, visitors returned once more to children in a room in which the last picture was W. Eugene Smith's iconic 1946 A Walk to Paradise Garden. As the centrepiece of the exhibition a hanging sculptural installation of photographs including Vito Fiorenza's Sicilian family group and Carl Mydans' of a Japanese family (both from nations which were recent enemies of the Allies in WW2), another from Bechuanaland by Nat Farbman and a rural family of the United States by Nina Leen, encouraged circulation to view double-sided prints and invited reflection on the universal nature of the family beyond cultural differences.The enlarged prints by the multiple photographers were displayed without explanatory captions, and instead were intermingled with quotations by, among others, James Joyce, Thomas Paine, Lillian Smith, and William Shakespeare, chosen by photographer and social activist Dorothy Norman. These texts, however effective in their creative challenge to the audience, the juxtaposition of such texts in apposition to the images reflects a not unexpected eurocentric bias.

The inclusion of quotes from the work of Lillian Smith, a writer and social critic of the Southern United States, and known most prominently for her best-selling novel Strange Fruit (1944), is noteworthy. A white woman who openly embraced controversial positions on matters of race and gender equality, she was a southern liberal unafraid to criticize segregation and work toward the dismantling of Jim Crow laws, at a time when such actions virtually guaranteed social ostracism.

Also included in the exhibition and in the exhibition publication was a poetic commentary by Carl Sandburg. The Wikipedia article on The Family of Man provides some quotations from the publication:

There is only one man in the world and his name is All Men. There is only one woman in the world and her name is All Women. There is only one child in the world and the child's name is All Children.

People! flung wide and far, born into toil, struggle, blood and dreams, among lovers, eaters, drinkers, workers, loafers, fighters, players, gamblers. Here are ironworkers, bridge men, musicians, sandhogs, miners, builders of huts and skyscrapers, jungle hunters, landlords, and the landless, the loved and the unloved, the lonely and abandoned, the brutal and the compassionate — one big family hugging close to the ball of Earth for its life and being. Everywhere is love and love-making, weddings and babies from generation to generation keeping the Family of Man alive and continuing.

If the human face is "the masterpiece of God" it is here then in a thousand fateful registrations. Often the faces speak that words can never say. Some tell of eternity and others only the latest tattings. Child faces of blossom smiles or mouths of hunger are followed by homely faces of majesty carved and worn by love, prayer and hope, along with others light and carefree as thistledown in a late summer wing. Faces have land and sea on them, faces honest as the morning sun flooding a clean kitchen with light, faces crooked and lost and wondering where to go this afternoon or tomorrow morning. Faces in crowds, laughing and windblown leaf faces, profiles in an instant of agony, mouths in a dumbshow mockery lacking speech, faces of music in gay song or a twist of pain, a hate ready to kill, or calm and ready-for-death faces. Some of them are worth a long look now and deep contemplation later.

A restored version of the historically significant photography exhibition The Family of Man has been installed permanently at Clervaux castle in Luxembourg, where the physical collection is archived and displayed. It was first opened to the public in 1994, following the restoration of the prints.The exhibition restored

In 2003 the Family of Man photographic collection was added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in recognition of its historical value.

. . . Clasp the hands and know

the thoughts of men in other lands . . .

John Masefield

The Family of Man, the afterlife . . .

Jerry Mason contemporaneously edited and published a complimentary book of the exhibition through Ridge Press. This book, which has never been out of print, was designed by Leo Lionni. Lionni’s book cover for The Family of Man, incorporate playful modernist collages of apparently cut or torn coloured paper, which he repeats, for example in his 1962 design for The American Character and for children’s books, an aesthetic also used in exhibitions from his parallel career as a fine artist.

The publication was reproduced in a variety of formats (most popularly a soft-cover volume) in the 1950s, and reprinted in large format for its 40th anniversary, and in its various editions has sold more than four million copies. Most images from the exhibition were reproduced with an introduction by Carl Sandburg, whose prologue reads, in part:

The first cry of a baby in Chicago, or Zamboango, in Amsterdam or Rangoon, has the same pitch and key, each saying, "I am! I have come through! I belong! I am a member of the Family. Many the babies and grownup here from photographs made in sixty-eight nations round our planet Earth. You travel and see what the camera saw. The wonder of human mind, heart wit and instinct is here. You might catch yourself saying, 'I'm not a stranger here.'

However, an omission from the book, highly significant and contrary to Steichen's stated pacifist aim, was the image of a hydrogen bomb test explosion; audiences of the time were highly sensitive to the threat of universal nuclear annihilation.

In place of the huge colour transparency to which a space was devoted in the MoMA exhibition, and the black-and-white mural print that toured countries other than Japan, only this quotation of Bertrand Russell's anti-nuclear warning, in white type on a black page, appears in the book;

[...] The best authorities are unanimous in saying that a war with hydrogen bombs is quite likely to put an end to the human race [...] There will be universal death — sudden for only a minority, but for the majority a slow torture of disease and disintegration.

Absent also from the book, and removed by week eleven of the initial MoMA exhibition, was the distressing photograph of the aftermath of a lynching, of a dead young African American man, Robert McDaniels, tied to a tree with his bound arms tautly tethered with a rope that stretches out of frame. McDaniels, together with Roosevelt Townes, were lynched on April 13, 1937, in Duck Hill, Mississippi by a white mob after being labeled as the murderers of a white storekeeper.

Slow torture

McDaniels and Townes had only been legally accused of the crime a few minutes before they were kidnapped from the courthouse, chained to trees, and tortured with a blow torch. Following the torture, McDaniels was shot to death and Townes was burned alive.On April 26, 1937, Time and Life magazines published a photograph of McDaniels' body chained to a tree. It was the first time an image of lynching had been published nationally. Other newspapers later published the image.

There was condemnation expressed across the country against the lynchings."Statesmen Quibble While a Mob Kills"

So the headline ran! Long Branch, New Jersey: The Daily Record. 22 April 1937. Excerpts from the story:

"The lynchers, of course, are the worse variety –– fiends for the hour committing mob murder with such maniacal brutality one wonders if they can be human.It is a crime peculiar to the United States –– a crime that has kept the people of other lands debating over what sort of brute is ranging upon the American continent. We can accuse the Nazi's of persecution, of bigotry and intolerance if we wish...but the Nazis can curse us a 'lynchers' and we must take it and like it.Lynching is ofttimes intolerance and hatred at its worse; there is nothing in foreign countries to approach it. What is more, the Congress of the United States –– the representatives of the people –– have defeated every attempt so far to wipe out the horror...and as their mad brethren in Mississippi were torturing these two citizens to death, the Congress was arguing whether there should be a law against it."

Internationally, German newspapers publicized the murders to support Nazi government propaganda, contrasting the violence of the lynchings to the "humane" Nuremberg racial laws that the Reich had passed against Jewish citizens.

The lynchings had also occurred at the moment that the House of Representatives was debating Rep. Joseph Gavagan's (Democrat -New York) anti-lynching legislation. The outrage helped gain support for anti-lynching legislation that he introduced. The legislation was supported in the Senate by Democrats Robert F. Wagner (New York) and Frederick Van Nuys (Indiana).

The legislation eventually passed in the House, despite 85 percent of the 123 Representatives from the South, voting against it. However, the powerful Solid South of white Democrats blocked it in the Senate, as they had blocked all previous anti-lynching bills.

Senator Allen Ellender (Democrat - Louisiana) proclaimed:

"We shall at all cost preserve the white supremacy of America."

Re:LODE Radio considers that the removal of this particular photo image is significant. It seems that this decision exposes how just one photo is potentially capable of disrupting the purpose of the project. The presence of this image, along with its connotative history, interrupts the ideological narrative.

It was an image with a specific history! And that specific history was (and is) an inconvenient truth!

The photo appeared under the title: "Death Slump at Mississippi Lynching (1937)." It was estimated to have been seen by more than 180,000 visitors in New York, however after receiving criticism of the photo for being "too powerful, too striking and causing visitors to pause and gaze, thus interrupting the flow of the movement and the flow of the message," curator Edward Steichen withdrew the image eleven weeks after the show opened:

"[I] felt that this violent picture might become a focal point in the reception of The Family of Man...[It] provided a form of dissonance to the theme, so we removed it for that purpose."

But what was this theme? The visual and spatial design of this spectacular exhibition of what looks to be, from the perspective of the end of 2020, a nascent type of conceptual art installation, and a modernist triumph, but, as Alise Tīfentāle says in her article for FKmagazine (2 Jul 2018) headlined:

The Family of Man: The Photography Exhibition that Everybody Loves to Hate

Alise Tīfentāle writes:The U.S. Information Agency popularized The Family of Man as an achievement of American culture by presenting ten different versions of the show in 91 cities in 38 countries between 1955 and 1962, seen by an estimated nine million people But, contrary to its popular reception, scholarly criticism of the exhibition was – and continues to be – scathing.

Re:LODE Radio chooses to re-present some of Alise Tīfentāle's article as it frames a problem that is familiar to the LODE project, when it comes to the question of how:

Colonialist thinking is skewing our view of everything?

The Family of Man was much more than the sum of all the images it featured. It offered an unusual visual experience. Made-to-order enlargements of various sizes were arranged as if on a magazine page, contrasting large images with smaller ones. The spatial arrangement of the exhibition added a distinct architectural aspect. The different sizes of the prints provided a dynamic rhythm of distinct emphases and background.

The unframed prints were mounted directly on panels, some of which were free-standing and removed from the wall, some others – hanging from the ceiling or arranged on a circular platform. These panels extended into the viewers’ space and created a visually interesting landscape that visitors were invited to explore. Their progress through the exhibition was limited to the route planned by the organizers because the panels were arranged in a maze-like way that guided visitors through the thematic sections from the entrance to the exit.

The scholarly reception of The Family of Man is greatly influenced by Roland Barthes who in 1957 criticized the exhibition for an essentialist depiction of human experiences such as birth, death, and work, and the removal of any historical specificity from this depiction. (Roland Barthes, “The Great Family of Man,” in Mythologies, transl. by Annette Lavers (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1972), 100-102.)

Re:LODE Radio notes the relevance of these paragraphs from The Nuclear Family of Man by John O'Brian published July 2, 2008, in Volume 6, Issue 7, of the Asia Pacific Journal, Japan Focus:

The Family of Man exhibition was greeted with wide critical approbation, both for the story it told as well as for how it told it. Although a few American commentators offered dissenting views – the photographer Walker Evans, for instance, whose work was not included in the show, wrote disdainfully of its “human familyhood [and] bogus heartfeeling” – the vast majority agreed with Carl Sandburg, brother-in-law of Steichen and author of the prologue to the catalogue, that here was “A camera testament, a drama of the grand canyon of humanity, an epic.”

It was these same qualities in the exhibition that drew the attention of Roland Barthes, The Family of Man’s most frequently cited early commentator. After seeing the exhibition in Paris in 1956, he declared it to be a product of “classic humanism,” a collection of photographs in which everyone lives and “dies everywhere in the same way.” “[T]o reproduce death or birth tells us, literally, nothing,” he wrote acerbically. The show suppressed “the determining weight of History” (Barthes’s capitalization), and thereby succumbed to sentimentality.

Barthes dismissed what he considered to be the exhibition’s repetitive banalities and its moralizing representation of world cultures, a view he correctly observed to have been drawn from American picture magazines. In fact, a sizeable part of the exhibition was chosen from back issues of Life and Look at a time when Europe, to say nothing of Japan, was being heavily subjected to the forces of Americanization.

Six months after the opening of The Family of Man, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African-American boy, was lynched in Mississippi for whistling at a white woman. The photographs of Till’s open coffin and mutilated face after he was pulled from the Tallahatchie River received international media coverage and was an early impetus for the American Civil Rights movement.

In his article for Paris Match, Barthes referred specifically to the lynching. “[W]hy not ask the parents of Emmett Till, the young Negro assassinated by Whites what they think about The Great Family of Man?” There was no place in the exhibition, Barthes implied, for historically specific photographs like those taken of Till at his open-coffin funeral.

Alise Tīfentāle's article continues:

Later, Allan Sekula viewed the exhibition as a populist ethnographic archive and “the epitome of American cold war liberalism” that “universalizes the bourgeois nuclear family” and therefore serves as an instrument of cultural colonialism. (Allan Sekula, “The Traffic in Photographs,” Art Journal 41, no. 1 (1981), 15-25.)

Christopher Phillips, on the other hand, criticized Steichen for silencing the voice of individual photographers by decontextualizing their photographs and imposing his own narrative. (Christopher Phillips, “The Judgment Seat of Photography,” October 22 (1982), 27-63.4)

Since the late 1990s, however, new and more nuanced readings of The Family of Man have emerged. Lili Corbus Bezner’s analysis of individual images included in the show reveals the heterogeneous visual content that was forced to fit into the framework of the populist surface and Steichen’s overarching narrative. (Lili Corbus Bezner, “Subtle Subterfuge: The Flawed Nobility of Edward Steichen’s Family of Man,” in Photography and Politics in America: From the New Deal into the Cold War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 121–174.)

Ariella Azoulay has argued that the exhibition can be viewed a visual equivalent to the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. (Ariella Azoulay, “The Family of Man: A Visual Universal Declaration of Human Rights” in Thomas Keenan and Tirdad Zolghadr, eds., The Human Snapshot (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), 19–48.)

New articles and book chapters are published on a regular basis. The approach that is the least exploited so far involves focusing our attention on individual images from the show and trying to figure out what they can tell us about the power relations in postwar photography.

Alise Tīfentāle's article then addresses the question of resistance and objection to the deformations and cultural violence that result from the colonial mindset. When it comes to the apparently straightforward task of framing images and information about the world and the people who inhabit this world, it's problematic!

Outsider Perspective

Although the prints in The Family of Man were not meant to be looked at as individual art works, they were still meant to be looked at. When audiences encountered the exhibition, not all viewers were pleased all the time. Some of the images turned out to be controversial and outraged some visitors. These cases reveal the chasm between the curator’s worldview and numerous other perspectives coming from cultures different than the U.S.One instance of violent public outrage took place at the Moscow instalment of The Family of Man in 1959. Theophilus Neokonkwo from Nigeria slashed and tore down prints by Polish-born American Life photographer Nat Farbman (1907–1988), taken in Bechuanaland (then a U.K. protectorate, since 1966 the Republic of Botswana). (Louis Kaplan, American Exposures: Photography and Community in the Twentieth Century (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 76. The sources do not specify exactly which prints were slashed by Theophilus Neokonkwo. The Family of Man featured five images by Nat Farbman from Bechuanaland. They appeared in different sections of the exhibition.)

One of the five images from The Family of Man, captioned “Bechuanaland. Nat Farbman. Life.”

Neokonkwo protested against the way in which the exhibition, according to his statement, depicted all non-Europeans, and especially Africans, “either half clothed or naked” and as “social inferiors” – as victims of illness, poverty, and despair, while white Americans and Europeans were represented mostly “in dignified cultural states – wealthy, healthy and wise.” (Theophilus Neokonkwo’s statement appeared in Afro-American (Washington, DC), August 22, 1959. Quoted from: Eric J. Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition: The Family of Man and 1950s America (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 155.)

This action was an attempt to critique the Western photojournalists’ tendency to exoticize all non-Western cultures – they were outsiders who visited for a short time and with the task of bringing back reportages as shocking as possible. Neokonkwo’s protest was an attempt to point to the power inequality that permitted the global circulation of images made by outsiders such as Farbman and his Life colleagues, but never provided equal space for photographs made by the insiders of non-Western cultures.One might ask – but were there any? Why don’t we know about them? Paraphrasing the title of the seminal article by second-wave feminist art historian Linda Nochlin, one might ask – Why have there been no famous non-Western photographers in the 1950s? (Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” ARTnews (January 1971)

There is no doubt that talented and skillful photographers lived and worked in many countries across the world. Among the reasons we do not know that much about their lives and work is that they never had such powerful employers as Life magazine and such mighty promoters as The Family of Man, whose world tour was backed by the U.S. government. The cultural clout, money, and professional development opportunities of a Life photojournalist who was carrying a U.S. passport in the 1950s could not be compared with the resources available to his fellow photographers from Bechuanaland, Nigeria, or many other countries.With LODE Zone Line in mind, as it crosses the Indian sub-continent, Re:LODE Radio is particularly interested in how Alise Tīfentāle's article then looks at how life in India is presented in The Family of Man exhibition.

Alise Tīfentāle writes:For example, in The Family of Man, thirteen images depict India.

Out of these thirteen, seven images explicitly focus on the suffering, the starving, the insane, the sick, and the dying. These images belong to the sensationalist shock-journalism of the human crisis that the illustrated magazines proliferated. A naked baby whose stomach is bloated from malnutrition sits on the floor and eagerly eats rice in an image by American photographer William Vandivert (1912–1989) working for Life magazine.

A group of elderly, starving, and desperately, dramatically grimacing women wrapped in rags are observed in close-up in an image by Magnum member, Swiss photographer Werner Bischof (1916–1954).

An emaciated, apparently severely ill or dying man with an empty stare and open mouth is laying on the ground in an image by Russia-born American photographer Constantin Joffé (1910–1992) working for Vogue magazine.

Out of the thirteen images depicting India in The Family of Man, only one was made by an Indian photographer – it is an image attributed to the film director Satyajit Ray (1921–1992) showing seemingly healthy and well-off children.

Unlike the majority of images in the exhibition, however, this image is not a documentary reportage, but a film still. The still is from Ray’s first and internationally highly acclaimed film Pather Panchali (1955). Because Ray was not known to be a photographer, and a designated photographer’s name does not appear in the film’s crew list, it is reasonable to assume that the author of this photograph was the film’s cinematographer, Subrata Mitra (1931–2001). This image was also used in one version of the film’s promotional poster.

Alise Tīfentāle's article then looks at how the FIAP Biennial, an idealistic project of the International Federation of Photographic Art (Fédération internationale de l’art photographique, FIAP) provided some redress during this period.

This organization was founded in Switzerland in 1950 with an aim to unite the world’s national associations of photographers. FIAP continues to exist to the present day. However, Alise Tīfentāle's article refers only to the work of FIAP during the 1950s and does not consider the later developments in the organization’s history and its changing role throughout the second half of the twentieth century. She writes about this under the heading:

Insider Perspective

Around the time of the world tour of The Family of Man, however, there was at least one organized attempt to bring to light work made by a more inclusive transnational group of photographers. It was the FIAP Biennial – an international exhibition of creative photography of an unprecedented scope at the time. The biennial, established in 1950, was conceived as a world survey of contemporary photographic art, displaying an equal number of works from each participating country. By 1955, FIAP represented photographers from thirty-six countries throughout the world: eighteen countries in Western Europe, eight countries in Latin America, five in Eastern Europe, four in Asia, one in Africa, and Australia.

Even with the best intentions, the Western photographers at times reproduced the worst cultural stereotypes of the colonial era. Meanwhile, Indian photographers who participated in FIAP aimed at creating a more positive view of their country. They tried to communicate that their country was not only impoverished, suffering, tumultuous, bizarre, cruel, “exotic,” “surrealistic” or whatever other adjectives Western journalists ascribed to it, but also a place where regular, dignified everyday life went on and where many people lived peacefully according to their religious beliefs and cultural traditions. When these Indian photographers presented their work in international forums, they wanted to tell different stories about life in independent India than those non-Indian photographers who traveled the world and produced images of “exotic” locations for consumption in Western European and U.S. illustrated magazines.

K. L. Kothary. No Work. Exhibited in the 1958 FIAP Biennial. Reproduction from the FIAP Yearbook 1960.

For example, in an image by Indian photographer K. L. Kothary, No Work, included in the 1958 FIAP Biennial, the frame includes the ends of four narrow boats, cutting them off on the left. The viewpoint is from above, and the frame is filled with an even surface of water. The horizon line or any other signifiers of the location of the scene are not visible. Two male figures occupy the two boats farthest away from the camera. One man has turned his back while the other is seen in profile. Their body language suggests that they may be engaged in a conversation with each other. The title suggests an awareness of the social circumstances they share. Yet the source of their unemployment is not specified – the viewers do not learn if the men have no work because the fishing season is over or has not started, or because of other, unknown reasons. Whether the two figures on their boats are fully employed or not, does not influence the perception of the image. Its main content is the rhythm of geometric shapes and an exploration of the flatness effect of the photographic image.

Vidyavrata. Music. Exhibited in the 1962 FIAP Biennial. Reproduction from the FIAP Yearbook 1964.

Another example is Music by Indian photographer Vidyavrata (1920–1999), included in the 1962 FIAP Biennial. Besides being a depiction of everyday life in a school, Music is a sophisticated study of photographic composition. From an elevated and quite distant viewpoint, the camera is looking down toward a row of ten children wearing white tank-top shirts and shorts. The children are aligned along a circle drawn on the floor. Inside the circle, there are nine empty chairs. Outside the circle, in the upper left corner of the frame, an adult oversees the proceeding of what likely is to be a game of musical chairs, a common gym activity in schools. The source of light is outside the frame, coming from the upper-left corner and positioned extremely low, suggesting either early morning or late evening light. The main visual feature of this image is the elongated shadows cast by the children that stretch diagonally to the lower-right corner. The dark shadows create a strong diagonal that intersects with the narrow white lines on the ground. Although children at play is one of the typical tropes of postwar humanist photography, here the author avoids superficial sentiment by keeping the children, the location, and circumstances of their play anonymous. Vidyavrata turns a potentially humanist subject matter into an exercise in modernist aesthetics. The compositional arrangement of bodies in space, distinct geometrical shapes and lines – not the children who are playing a game – become the main elements of the work.

Shreedam Bhatt. Listening to the Scriptures. Exhibited in the 1958 FIAP Biennial. Reproduction from the FIAP Yearobok 1960.

Another example is Listening to the Scriptures by Shreedam Bhatt (life dates unknown), a photographer from the Ahmedabad area. This image, featured in the 1958 FIAP Biennial, captures a group of bearded men sitting on the ground and attentively looking at another man on the left side of the frame who appears to be reading from a book. The group of men takes up most of the frame, and the photograph does not provide much detail to describe the location more specifically apart from a fragment of a low, makeshift rural building in the background. The men sit on top of a special platform in the center of a village – this kind of elevated seating was used for religious holidays, reading ordinances, and funerals. The situation may be part of a funeral ritual or a public reading of an ordinance. The image depicts the life of ordinary people as observed in their natural settings and in an un-posed manner. The photograph is taken at the eye level of the sitting men, thus positioning the viewer among them. This is a very intimate insight into the life of a small village deep in the countryside, which, likely, would not be so easily available for traveling Western photographers – and they would not be interested in capturing a scene of everyday life without any “exotic” practices going on and without anybody visibly sick, starving, or dying.

Through their choice of photographic form – thoughtful compositions, careful arrangement of figures, mastery of unusually positioned light sources and capturing of shadows – Indian photographers attempted to communicate some of their ideals about an independent India in a visual language that they hoped would be understood and appreciated by their peers across the world. Their images attempted to position normalcy and everydayness against Western exoticization and the reporters’ interest in finding chaos, poverty, famine, illness, and misery. Indian photographers responded to the negative cultural stereotypes nurtured by exhibitions such as The Family of Man. Their images attempted to communicate that India was more than starving babies and the dying poor. But, of course, their story is not the one that has so far been central to the history of photography.

Alise Tīfentāle's article takes a view of the difference between outsiders and insiders where power relations in a post-war setting, described as a cold war, produced quite different versions of a photography that, as photography always does, substituted itself for the realities being documented. She writes:

The FIAP Biennial and The Family of Man shared a global ambition and aim to represent the world through photography. However, the ways in which both exhibitions envisioned such representation were quite different. The Family of Man demonstrated how the world looked like through the eyes of – mostly – U.S.-based professional photojournalists who traveled to all corners of the globe. The FIAP Biennials, meanwhile, demonstrated how the world looked like through the eyes of photographers who actually lived and worked in all corners of the world. The Family of Man offered a uniform outsider perspective of a vast range of cultures and nations, while the FIAP Biennials provided a vast range of insider perspectives coming from within these cultures. FIAP’s idealistic attempt to give voice to the world’s photographers eventually went unnoticed, largely because of lacking funding and support from the narrow elite of Western European and U.S. professionals.

Was "The Family of Man" another moment in the ongoing Americanisation of the world?

Out of Africa - A group of Afro-Colombian women along the LODE Zone Line

The Americanisation of the World, and the false consciousness inherent in a "eurocentric" world view of things, is discussed in the ReLODE article Eurocentrism found in the Re:LODE Methods & Purposes section.

When it comes to it, Re:LODE Radio concurs with Allan Sekula in 'The Traffic in Photographs' (1981) where he considers The Family of Man functions as a capitalist cultural tool levering world domination at the height of the Cold War; "My main point here is that The Family of Man, more than any other single photographic project, was a massive and ostentatious bureaucratic attempt to universalize photographic discourse," an exercise in hegemony which, "In the foreign showings of the exhibition, arranged by the United Scates Information Agency and co-sponsoring corporations like Coca-Cola, the discourse was explicitly that of American multinational capital and government–the new global management team–cloaked in the familiar and musty garb of patriarchy." Sekula revises and expands this notion in relation to his ideas about economic globalisation in an article in October entitled "Between the Net and the Deep Blue Sea: Rethinking the Traffic in Photographs".

To quote again from The Nuclear Family of Man by John O'Brian published July 2, 2008, in Volume 6, Issue 7, of the Asia Pacific Journal, Japan Focus:

Under the auspices of the United States Information Agency the exhibition traveled the world, beginning its European tour in West Berlin and a second tour in Guatemala City. The logic of these two cities as the initial points of departure was dictated by Cold War diplomacy. Berlin was divided into competing Communist and Western sectors, and in Guatemala CIA-backed forces had recently overthrown the democratically elected pro-Communist government of Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán. Four different versions of the exhibition were produced for Japan alone. By the end of 1956 almost a million people in Japan had seen it, roughly 10% of the audience for the exhibition worldwide.

In deference to the experience of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, however, a large black-and-white photographic image of a mushroom cloud included in other traveling versions of the exhibition was omitted.

Instead, photographs taken by Yamahata in Nagasaki on the day following the explosion were substituted. These images showed, as the photographs in The Family of Man did not, the human toll and devastation caused by the bomb. Soon, however, they were censored as well. When the emperor visited The Family of Man in Tokyo, Yamahata’s photographs were curtained off and then removed altogether from the exhibition.

The Family of Man was a benign cultural demonstration of American political values. From the point of view of cultural diplomacy it was a spectacular success, even traveling to Moscow in 1959. The exhibition formed part of the American National Exhibition in Sokol’niki Park, the site of the infamous Krushchev-Nixon kitchen debate, occupying its own building adjacent to pavilions housing displays of automobiles, refrigerators, model homes, stereo equipment, vacuum cleaners, color televisions, air conditioners, Pepsi-Cola and other commodities of capitalist prosperity provided by American corporations for the occasion.

As part of the bureaucracy charged with advancing American foreign policy, the role of the United States Information Agency was to help to undermine Communism, promote capitalism and spread democracy – and to do so quietly. “[W]here USIA output resembles the lurid style of communist propaganda,” a directive warned, “it must be unattributed.” The United States had to appear to be going about its business softly. The Official Training Book for Guides at Sokol’niki Park makes no mention of Communism, capitalism or democracy and says only that the United States hopes to demonstrate “how America lives, works, learns, produces, consumes, and plays.” This anodyne string of verbs parallels those used to describe, in press releases and news reports, the intentions of The Family of Man. The exhibition’s message of commonality meshed seamlessly with the global ambitions of American liberalism and multinational capital. People are everywhere the same, so the slogans of universality and corporate desire go, and every house must have a refrigerator. The photographer Tomatsu Shomei, a critic of both the Occupation and the accompanying rush towards Americanization, later commented:

“The message is that everyone is happy – but is everyone really that happy?”

The United Colors of Benetton

Is everyone really that happy? Perhaps this question should underscore the "United Colors" advertising campaign for Benetton and its slogan of the early 1980's:

"All the colors of the world"

The aesthetic of Benetton's ad campaigns changed, along with the activist intentions of Oliviero Toscani, the Italian photographer known worldwide for designing a series of controversial advertising campaigns for Italian brand Benetton, from 1982 to 2000. As part of an anti-racism campaign in 1996 these ‘human’ hearts were later to be revealed to be pig’s hearts. But that didn’t stop people all over the world calling the image, taken by Oliviero Toscani himself, racist. Toscani has used his advertising to address racism on numerous occasions.

UNHATE

This image was used in a Guardian Fashion piece (Thu 17 Nov 2011) on: Benetton's most controversial adverts

Will a picture of the Pope kissing Ahmed el-Tayeb, Sheikh of the al-Azhar mosque, encourage fashion savvy shoppers to ditch Uniqlo and buy their brightly coloured jumpers from Benetton instead? Probably not. But it does remind the public that the Italian brand has quite a history of provocative campaigns.

A still from the James and other apes campaign, 2004: Benetton says:

'This campaign was made with the support of the Jane Goodall Institute, founded by the renowned primatologist who is a committed defender of the environment and a UN Messenger of Peace. Through this initiative, Benetton continued its exploration of diversity as a 'wealth' of our world, extending it from the variety of human races to embrace the living beings that are our closest cousins. The portraits of these great apes make us ponder the fundamental questions of mankind, reflected in the enigmatic gaze of races so close to us on the evolutionary ladder'.

Human kind

When it comes to ideas about human kind, Hilton Kramer, then managing editor of the magazine Arts, was quick to assert a negative view that The Family of Man exhibition was a;

"self-congratulatory means for obscuring the urgency of real problems under a blanket of ideology which takes for granted the essential goodness, innocence, and moral superiority of the international 'little man'; 'the man in the street': the active, disembodied hero of a world-view which regards itself as superior to mere politics."

Rutger Bregman would, perhaps, offer the thought that maybe such a view of human kind plays into the hands of those who would prefer that "things stay the way they are"?

Rutger Bregman is familiar to Re:LODE Radio as the Dutch popular historian and author, who in January 2019 took part in a panel debate at the World Economic Forum in Davos, where he criticised the event for its focus on philanthropy rather than tax avoidance and the need for fair taxation. His intervention was widely reported and followed on social media.

During a February 2019 interview in Amsterdam with Fox News anchor and journalist, Tucker Carlson after Davos, Bregman told Carlson that the United States "could easily crack down on tax paradises" if they wanted to and that Fox News would not cover stories about tax evasion by the wealthy. He said that Carlson himself, had been taking "dirty money" for years from the CATO Institute where he was senior fellow and which is "funded by Koch billionaires" — Charles Koch and David Koch. He said that Carlson and other Fox News anchors are "millionaires paid by billionaires" — referring to the Murdochs and, in Carlson's case, the Koch brothers. Bregman told Carlson that "what the Murdochs want you to do [on Fox News] is scapegoat immigrants instead of talking about tax avoidance". Carlson was angered by Bregman's comments. Bregman posted a video of his unaired interview with Carlson on NowThis News on YouTube on 20 February 2019. By July the video had received 2,349,846 views.

Rutger Bregman begins the first chapter of his book:

Human kind: A Hopeful History, “A New Realism”,

with this short sentence:

“This book is about a radical idea”.

The next sentence in the following paragraph begins with an observation concerning this idea:

"An idea that’s long been known to make rulers nervous."

An idea denied by religions and ideologies, ignored by the news media and erased from the annals of world history. At the same time, it's an idea that’s legitimised by virtually every branch of science. one that is corroborated by evolution and confirmed by everyday life. An idea so intrinsic to human nature that it goes unnoticed and gets overlooked.

If only we had the courage to take it more seriously, it an idea that might just start a revolution. Turn society on its head. Because once you grasp what it really means, it’s nothing less than a mind-bending drug that ensures you’ll never look at the world the same again.

So what is this radical idea?

That most people, deep down, are pretty decent.

Steven Poole, reviewing Bregman's book Human kind: A Hopeful History, for the Guardian (Wed 10 Jun 2020), points out that the thesis that relies on a basic quality of human decency, is as much a fairytale as the notion of human wickedness. He writes:

But plainly the attempt to replace a story about humans’ essential wickedness with a contrasting story about humans’ essential loveliness has already run aground – as it was bound to, since any claim that complex human beings are essentially one single thing or another is a fairytale. “I’ve argued that humans have evolved to be fundamentally sociable creatures,” Bregman writes – as though this is a brave thing to argue, though absolutely no one in the world disagrees with it – “but sometimes our sociability is the problem.” Well, sure. Gun-toting anti-lockdown protesters in the US are being sociable; so are criminal gangs and far-right activists. On the other hand, because things are more complicated than such books allow, sometimes being anti-social is the problem.

Re:LODE Radio prefers Marshall McLuhan's fallacy, a fallacy that rests on the foundational importance of the modes of communication between people. Modes of communication create the environment that shapes both the behaviours and attitudes of humankind, to everything. A fallacy is normally understood as the use of an invalid or otherwise faulty reasoning, or "wrong moves" in the construction of an argument. When McLuhan uses the term in the film Annie Hall, he is using the term in a way that relates more to argumentation theory.

Woody Allen says . . .

Argumentation theory provides a different approach to understanding and classifying fallacies. In this approach, an argument is regarded as an interactive protocol between individuals that attempts to resolve their disagreements. The protocol is regulated by certain rules of interaction, so violations of these rules are fallacies.

Fallacies are used in place of valid reasoning to communicate a point with the intention to persuade. Examples in the mass media today include but are not limited to propaganda, advertisements, politics, newspaper editorials and opinion-based “news” shows.

Colonial thinking, the theme that runs through this text/image piece, is a hybrid form, coming out of print technology, print culture, and the exchangeable, and movable "types" of capitalism, and the commodification of everything.

One of the examples Bregman uses in the first pages of his book to illustrate this hidden truth is taken from the crisis faced by the people of Louisiana and New Orleans as Hurricane Katrina, one of the now increasingly frequent extreme weather events in the Caribbean and Atlantic caused by global heating, blew in across the coast and caused catastrophic damage to the poorly engineered flood defences of the city.

On 29 August 2005, Hurricane Katrina tore over New orleans. The levees and flood walls that were supposed to protect the city failed. In the wake of the storm, 80 per cent of area homes flooded and at least 1,836 people lost their lives. It was one of the most devastating natural disasters in US history.

That whole week newspapers were filled with accounts of rapes and shootings across New Orleans. There were terrifying reports of roving gangs, looting and of a sniper taking aim at rescue helicopters.

Inside the Superdome, which served as the city’s largest storm shelter, some 25,000 people were packed in together, with no electricity and no water. Two infants’ throats had been slit, journalists reported, and a seven-year-old had been raped and murdered.

The chief of police said the city the city was slipping into anarchy, and the governor of Louisiana feared the same. ‘What angers me the most,’ she said, ‘is that disasters like this often bring out the worst in people.’

This conclusion went viral. In the British newspaper the Guardian, acclaimed historian Timothy Garton Ash articulated what so many were thinking. ‘Remove the elementary staples of organised, civilised life - food, shelter, drinkable water, minimal personal security - and we go back within hours to a Hobbesian state of nature, a war of all against all. [ . . . ] A few become temporary angels, most revert to being apes.’

There it was again, in all its glory: veneer theory. New Orleans, to Garton Ash, had opened a small hole in ‘the thin crust we lay across the seething magma of nature’.

Re:LODE Radio considers the language quoted here from Garton Ash’s Guardian opinion piece is loaded with a matrix of the mixed meanings that can found in the use of the word “nature”, that is, according to Raymond Williams, perhaps the most complex word in use in the English language. For Re:LODE Radio the particular example reveals more than a tinge of a colonialist, even racist colour. Re:LODE Radio is not pointing the finger of racism at Tim Garton Ash, but is pointing to the use of language, as part of a constructed ideological overlay, that is highly functional in obscuring the actuality, the truth!

Rutger Bregman then exposes this alternative reality, with its alternative facts, as part of the myth;

that by their very nature humans are selfish, aggressive, and quick to panic. It’s what Dutch biologist Frans de Waal likes to call veneer theory: the notion that civilisation is nothing more than a thin veneer that will crack at the merest provocation. In actuality, the opposite is true. It’s when crisis hits - when the bombs fall or the floodwaters rise - that we humans become our best selves.

Re:LODE Radio comments that these particular qualities attributed to “human kind”, of selfishness, of aggressiveness, of a tendency to panic, are qualities that reflect the typical capitalist response to anything that threatens the global capitalist world order.

Rutger Bregman continues.

It wasn’t until months later, when the journalists cleared out, the floodwaters drained away and the columnists moved on to their next opinion, that researchers uncovered what had really happened in New Orleans.

What sounded like gunfire had actually been a popping relief valve on a gas tank. In the Superdome, six people had died: four of natural causes, one from an overdose and one by suicide. The police chief was forced to concede that he couldn’t point to a single officially reported rape or murder. True, there had been looting, but mostly by groups that had teamed up to survive, in some cases even banding with police.

Researchers from the Disaster Research Center at the University of Delaware concluded that the ‘overwhelming majority of the emergent activity was prosocial in nature’. A veritable armada of boats from as far away as Texas came to save people from the rising waters. Hundreds of civilians formed rescue squads, like the self-styled Robin Hood Looters - a group of eleven friends who went around looking for food, clothing and medicine and then handing it out to those in need.

Katrina, in short, didn’t see New Orleans overrun with self-interest and anarchy. Rather, the city was inundated with courage and charity.

The hurricane confirmed the science on how human beings respond to disasters. Contrary to what we normally see in the movies, the Disaster Research Center at the University of Delaware has established that in nearly seven hundred field studies since 1963, there’s never total mayhem. It’s never every man for himself. Crime - murder, burglary, rape - usually drops. people don’t go into shock, they stay calm and spring into action. ‘Whatever the extent of the looting,’ a disaster researcher points out, ‘it always pales in significance to the widespread altruism that leads to free and massive giving and sharing of goods and services.’

Hurricane Katrina, in 7 essential facts

This Vox article by German Lopez, ten years after the hurricane hit New Orleans, sets out the facts.

Hurricane Katrina was not a natural disaster, it was a disaster of rightwing political arms length, "hands off" style and administrative incompetence, and paranoia. This administrative disaster was compounded by the mobilisation of essentially racist and classist psychological projections, dumped onto a largely entirely innocent, law abiding, but poor, Afro American population.

This article by Laura Lein for THE CONVERSATION, writing ten years on from the hurricane, draws attention to the fact that this urban population is:

Still waiting for help

This article by Nicholas Lemann for The New Yorker, August 26 2020, on the occasion of the publication of a new history of the event, "Katrina" by the historian Andy Horowitz of Tulane University.

Nicholas Lemann writes:

When we came home to New Orleans for the first time after Hurricane Katrina, over Thanksgiving weekend of 2005, my then three-year-old son, looking out the window on the drive in from the airport, said, “You told me we were going to New Orleans, but now we’re in Iraq.” This was three months after the storm hit. The floodwaters had receded, the Superdome had emptied, the national press had left, and we weren’t anywhere near the city’s most famous devastated neighborhood, the Lower Ninth Ward—but still what you saw was a landscape of abandoned buildings, moldy refrigerators set out on sidewalks, downed trees and electrical wires, and a thick impasto of mud covering everything. Even now, fifteen years after Katrina, New Orleans has not fully recovered, in population and otherwise.

By the standards of one’s middle-school geography class, New Orleans ought to be one of America’s most prosperous cities, instead of one of its poorest. It is the natural port for the vast interior of the country, from the Rockies to the Appalachians. In its immediate vicinity are many natural resources: rich soil for growing rice and sugarcane, and plenty of cotton, sulfur, seafood, and, beginning in the early twentieth century, oil. Then there are the city’s celebrated charms—the food, the music, the generally soft, seductive atmosphere. But New Orleans peaked, relative to other American cities, back in 1840, and has been losing ground ever since. It looks today like an especially severe example of the resource curse, because its economy of extraction was based originally on slavery—antebellum New Orleans was the country’s leading marketplace for the buying and selling of humans—and then on Jim Crow, which generated a system of exploitation that pervades every local institution, as well as a deep, evidently permanent mistrust between the races.

And then there is New Orleans’s relationship to nature. Half of the city is below sea level; only a relatively small portion, the section that was originally settled, is habitable by traditional definitions. The city is surrounded by an endless borderland that shifts between river, marsh, swamp, and ocean. Katrina was only one of a long series of hurricanes that have struck near the mouth of the Mississippi. In New Orleans, civic monumentalism was always bound up in the racial order—consider the Confederate statues that the city built, in the early twentieth century, and only recently removed—but not every expression of it was explicitly racial. Another important project, from the same period, was the creation of an elaborate system of drains and pumps, supervised by an engineer named A. Baldwin Wood, which was supposed to make the entire area within the great crescent bend of the river, all the way to the shore of Lake Pontchartrain, permanently flood-proof. As Andy Horowitz, a young historian at Tulane University, writes in “Katrina,” his new history of the event, it was twentieth-century New Orleans—the part built after the drainage system was constructed—that flooded in the late summer of 2005.

Bad news sells . . .

. . . in the society of the spectacle!

Re:LODE Radio points to The Society of the Spectacle (French: La société du spectacle), the 1967 work of philosophy and Marxist critical theory by Guy Debord, in which the author develops and presents the concept of the Spectacle. The book is considered a seminal text for the Situationist International movement.

The work is set out as a series of 221 short theses in the form of aphorisms. Each thesis contains one paragraph. Here quoted are the first ten theses from Chapter 1: The Culmination of Separation, preceded by a quote from Feuerbach, in his Preface to the second edition of The Essence of Christianity.

“But for the present age, which prefers the sign to the thing signified, the copy to the original, representation to reality, appearance to essence ... truth is considered profane, and only illusion is sacred. Sacredness is in fact held to be enhanced in pro- portion as truth decreases and illusion increases, so that the highest degree of illusion comes to be the highest degree of sacredness.”Feuerbach, Preface to the second edition of The Essence of Christianity.

1In societies dominated by modern conditions of production, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.2The images detached from every aspect of life merge into a common stream in which the unity of that life can no longer be recovered. Fragmented views of reality regroup themselves into a new unity as a separate pseudoworld that can only be looked at. The specialization of images of the world evolves into a world of autonomized images where even the deceivers are deceived. The spectacle is a concrete inversion of life, an autonomous movement of the nonliving.3The spectacle presents itself simultaneously as society itself, as a part of society, and as a means of unification. As a part of society, it is the focal point of all vision and all consciousness. But due to the very fact that this sector is separate, it is in reality the domain of delusion and false consciousness: the unification it achieves is nothing but an official language of universal separation.4The spectacle is not a collection of images; it is a social relation between people that is mediated by images.5The spectacle cannot be understood as a mere visual excess produced by mass-media tech- nologies. It is a worldview that has actually been materialized, a view of a world that has become objective.6Understood in its totality, the spectacle is both the result and the project of the dominant mode of production. It is not a mere decoration added to the real world. It is the very heart of this real society’s unreality. In all of its particular manifestations — news, propaganda, advertis- ing, entertainment — the spectacle represents the dominant model of life. It is the omnipresent affirmation of the choices that have already been made in the sphere of production and in the consumption implied by that production. In both form and content the spectacle serves as a total justification of the conditions and goals of the existing system. The spectacle also represents the constant presence of this justification since it monopolizes the majority of the time spent outside the production process.7Separation is itself an integral part of the unity of this world, of a global social practice split into reality and image. The social practice confronted by an autonomous spectacle is at the same time the real totality which contains that spectacle. But the split within this totality mutilates it to the point that the spectacle seems to be its goal. The language of the spectacle consists of signs of the dominant system of production — signs which are at the same time the ultimate end-products of that system.8The spectacle cannot be abstractly contrasted to concrete social activity. Each side of such a duality is itself divided. The spectacle that falsifies reality is nevertheless a real product of that reality. Conversely, real life is materially invaded by the contemplation of the spectacle, and ends up absorbing it and aligning itself with it. Objective reality is present on both sides. Each of these seemingly fixed concepts has no other basis than its transformation into its opposite: reality emerges within the spectacle, and the spectacle is real. This reciprocal alienation is the essence and support of the existing society.9In a world that is really upside down, the true is a moment of the false.10The concept of “the spectacle” interrelates and explains a wide range of seemingly unconnected phenomena. The apparent diversities and contrasts of these phenomena stem from the social organization of appearances, whose essential nature must itself be recognized. Considered in its own terms, the spectacle is an affirmation of appearances and an identification of all human social life with appearances. But a critique that grasps the spectacle’s essential character reveals it to be a visible negation of life — a negation that has taken on a visible form.Degradation of human lifeDebord traces the development of a modern society in which authentic social life has been replaced with its representation. as he writes in thesis 1: "All that once was directly lived has become mere representation." Debord argues that the history of social life can be understood as "the decline of being into having, and having into merely appearing." (thesis 17) This condition, according to Debord, is the "historical moment at which the commodity completes its colonization of social life." (thesis 42)